Difference between revisions of "Book/The Medium-Specific Narrative"

Thaumasnot (talk | contribs) |

Thaumasnot (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 541: | Line 541: | ||

Such tropes can be seen as '''global invariants'''. They help to categorize the whole work, and they abstract time away. If a critic categorizes a movie as ''neo-noir'', then you can expect a certain tone, certain types of characters, and stories. Even though they are presented on a timeline, they become features of a finished, non-evolving product; they become constants. The apparent lack of temporality is most striking in music, arguably the temporal medium ''par excellence''. The reader of a book can read the description of a scene and paint the scene in his head. Although the reading itself is temporal, the scene it renders can be static and atemporal. In a way, the reader can pretend the reading experience was atemporal. It doesn’t matter whether the reader reads “a blue sky was seen” or “the sky I saw was blue.” Although the order of the words, their temporality in the reader’s frame of reference, change, they usually mean the same to the interpreter who projects them into a still image. In music, atemporality is somewhat more difficult to pretend, because music imposes a tempo on the listener. One could conceive that a reader with photographic memory can “read” pages in the blink of an eye. By contrast, music only reveals itself at its own pace. Yet, in classical music, one is used to designate the pieces of a concerto or symphony by a “blanket tempo.” A Vivaldi concerto, for example, is often divided into 3 movements identified by the tempo, usually: ''Allegro'' (fast), ''Largo'' (slow), then ''Allegro'' (fast). Each movement’s “velocity” is never as strictly uniform as the tempo would suggest. It’s like velocity had been made into an atemporal category by abstracting away the velocity changes inside the same movement. Similarly, some people identify and categorize a piece of music by its harmonic scale. | Such tropes can be seen as '''global invariants'''. They help to categorize the whole work, and they abstract time away. If a critic categorizes a movie as ''neo-noir'', then you can expect a certain tone, certain types of characters, and stories. Even though they are presented on a timeline, they become features of a finished, non-evolving product; they become constants. The apparent lack of temporality is most striking in music, arguably the temporal medium ''par excellence''. The reader of a book can read the description of a scene and paint the scene in his head. Although the reading itself is temporal, the scene it renders can be static and atemporal. In a way, the reader can pretend the reading experience was atemporal. It doesn’t matter whether the reader reads “a blue sky was seen” or “the sky I saw was blue.” Although the order of the words, their temporality in the reader’s frame of reference, change, they usually mean the same to the interpreter who projects them into a still image. In music, atemporality is somewhat more difficult to pretend, because music imposes a tempo on the listener. One could conceive that a reader with photographic memory can “read” pages in the blink of an eye. By contrast, music only reveals itself at its own pace. Yet, in classical music, one is used to designate the pieces of a concerto or symphony by a “blanket tempo.” A Vivaldi concerto, for example, is often divided into 3 movements identified by the tempo, usually: ''Allegro'' (fast), ''Largo'' (slow), then ''Allegro'' (fast). Each movement’s “velocity” is never as strictly uniform as the tempo would suggest. It’s like velocity had been made into an atemporal category by abstracting away the velocity changes inside the same movement. Similarly, some people identify and categorize a piece of music by its harmonic scale. | ||

Such blanket concepts are a product of narrative features becoming identifiable and well-known invariants. However, the more unique the narrative, the less blanketable it becomes. The aforementioned medium-specific narrative of ''Ode to a Grecian Urn'' doesn’t have (yet) a blanket term because it is fairly specific, although each step of the narrative is individually unremarkable. As a consequence, I can only communicate the whole narrative by going through all 4 steps of the narrative in order, recreating the temporal structures therein. | Such blanket concepts are a product of narrative features becoming identifiable and well-known invariants. However, the more unique the narrative, the less blanketable it becomes. The aforementioned medium-specific narrative of ''Ode to a Grecian Urn'' doesn’t have (yet) a blanket term because it is fairly specific, although each step of the narrative is individually unremarkable. Some steps are clearly about repetition, but through the filter of a specific narrative. As a consequence of specificity, I can only communicate the whole narrative by going through all 4 steps of the narrative in order, recreating the temporal structures therein. | ||

Yet, blanket concepts sometimes are declared as attempts to capture uniqueness. I was once in a music theory class where Chopin’s music was characterized by its “question/answer structures.” That is, the phrases played in succession on the piano almost sound like a dialogue between different instruments. This sounds on point. But, come to think of it, one can actually say the same thing of any piece of music. It’s not only the phrases that engage into a dialogue. A phrase can usually be divided into segments that compete to express their individual voices. Division is recursive and can reach down to the level where notes compete against each other. The levels of division don’t have to be mutually exclusive; they actually coexist. Notes are particular cases of segments that enter into the composition of larger segments and phrases, and the particular multidimensional way in which the dialogues take life in some medium-specific narrative is just part of a discovery. | Yet, blanket concepts sometimes are declared as attempts to capture uniqueness. I was once in a music theory class where Chopin’s music was characterized by its “question/answer structures.” That is, the phrases played in succession on the piano almost sound like a dialogue between different instruments. This sounds on point. But, come to think of it, one can actually say the same thing of any piece of music. It’s not only the phrases that engage into a dialogue. A phrase can usually be divided into segments that compete to express their individual voices. Division is recursive and can reach down to the level where notes compete against each other. The levels of division don’t have to be mutually exclusive; they actually coexist. Notes are particular cases of segments that enter into the composition of larger segments and phrases, and the particular multidimensional way in which the dialogues take life in some medium-specific narrative is just part of a discovery. | ||

Revision as of 10:46, 15 November 2016

Interpretation of the “medium-specific narrative”

The alternative to the interpretation of the average value is what, in the absence of a more marketable expression, I call the “medium-specific narrative.” It is the opposite of the mosaic. Instead of a loose whole, one searches for some tightly-knit functional structure, with all extras removed. The medium-specific narrative that the creator is supposed to have designed, intended, and wanted for their audience isn't the only narrative in a work of art. A particular narrative may occasionally coincide with that notion, but in general, it is more modest in its scope and fundamentally hedonistic: the joy comes from finding one that is satisfying enough in a purely subjective sense.

Narrative interpretation is an endeavor to view the work as, broadly speaking, a “story,” i.e., every element in the work is viewed in light of previous elements, the premises. If the elements form a succession of events that share a timeline, characters, locations, etc., then we recognize the traditional concept of story. But if the elements are the regions of a painting or the melodic motifs of a song, the concepts of “story” and “premise” take on a peculiar quality relative to the nature of the medium. In a pop song, an element could be the chorus, and premise would be the verse. Depending on the merits of doing so, one could look at a more granular level, and take “element” to mean a motif or melodic pattern. Such an element can become a “premise” to an element that follows it within the song’s timeline. In a painting, an “element” could, for example, mean a painted region, an object, or a motif. The concept of “premise” here can be somewhat misleading, as there isn’t always a declared timeline. In this case, I like to generalize the definition of “premise” to mean “another element of the painting.” The elements of a painting implicitly bond together through an implicit timeline, even if the observer tends to compress this timeline in a process similar to photographic memory. I’m talking about the timeline of the viewing experience. The movement of the viewer’s gaze from one region of the painting to another creates a subjective timeline of perceptions, a “story” of perceptions.

Note that the physical frame of the narrative (the canvas, the page, or the MP3 file) is a convention. It is a guide that narrows the search for narratives. But you could imagine looking for (and finding) medium-specific narratives in Nature or in any unintended arrangement of objects. This has important ramifications for how one looks at conventional art. The focus is now on the perceptions as they happen to the observer, not as they are intended by some benevolent being. Not coincidentally, the mosaic automatically begins to arise when one talks of such a benevolent being, a Creator or Artist, in relation to the work. This shows how fundamentally different the medium-specific narrative is from the interpretation of the average value in its cognitive approach.

The “medium specificity” of the narrative means that the elements of the narrative stay homogeneous with respect to each other as parts of the same medium, in the sense that they change into each other as part of a narrative. This implies that the narrative stays intra-medium. Intuitively, it defines the whole work as the self-contained unit of interpretation, in a way that frames the content as events that happen on a closed timeline. As a medium-specific narrative, a song is a succession of elements that actually occur to the listener (melodies, patterns, etc.) and nothing else. By contrast, the interpretation of the average value creates a mosaic of features, including mood, theme, and genre, thus rendering the content very generic. Before mood, theme, or genre, the listener first experiences medium-specific narratives: narratives of notes, of phrases, of sections. Theme or genre are high-level products that are generic and abstract the granularity of the medium-specific narratives.

Don’t get me wrong: an interpretation of the average value has its uses, even if you only get a coarse picture of the content. Even if the work is incredibly bad, the interpretation of the average value is valuable for telling as much. Comparatively, the interpretation of the medium-specific narrative relies entirely on the objective content. If the work is a boring mass of clichés, the medium-specific narrative will be about the objective content of this boring mass of clichés. The value of its interpretation is essentially the value the interpreter found in some medium-specific narrative within the content, but the value judgment is not explicit. Instead, it is implicitly encoded in the very existence of the interpretation as a statement of interest. This interest is expressed in the way in which the uninterpreted content differs from the content as rendered by the interpretation. This difference necessarily exists. An interpretation of a painting is text, and text is never equivalent to visuals. It would be pointless to try to translate every graphical nuance into words (the visuals do a better and infinitely more concise job of it anyway). Instead, the interpreter cherry-picks the elements that mattered to him and writes them down in text form. This selection process already conveys a positive judgment value, as people don’t usually enjoy spending brain time writing down medium-specific narratives they find unremarkable.

Although the interpretation of the medium-specific narrative may implicitly say, “This work is great,” like the interpretation of the average value, it carries an altogether different legacy. The point isn’t the significance of being liked or not, but the narrative itself—a constructive concept that lives independently of value judgment and can be communicated objectively. Even if you don’t like it, you get a chance to learn about something constructive in the content. Metaphorically, this is the explanation of the joke that you didn’t find amusing. It may leave you unamused, but it can also teach you something new.

The interpretation of the interpretation of the average value as an interpretation of the medium-specific narrative of reviews

The interpretation of the average value reveals itself when one begins to question reviews, and hold their narratives more accountable for the meaning they imply, rather than the meaning claimed by their author or the readers. In a way, reviews are works of art about works of art, an “artful” form of thought process based on content amnesia. This thought process is not confined to art, and can easily be applied to other fields. It blurs the lines between art and science, between theory and practice, between fiction and reality. It turns out that one can also always look for narratives not only in art, but in any kind of text, serious or not, belonging to expert domains or everyday life. In fact, most critiques and analyses you will find in this text are interpretations of the medium-specific narratives of various papers, books, discourses, reviews, and everyday chatter. The medium-specific narratives are processed for easy reading, while staying recognizable by the characteristic minuteness with which they capture how the words chain together, rather than by an enumeration of a mosaic’s features.

A medium-specific narrative from John Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn

I chose John Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn because it is short and well-established in academic circles.

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time, Sylvan historian, who canst thus express A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme: What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape Of deities or mortals, or of both, In Tempe or the dales of Arcady? What men or gods are these? What maidens loth? What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d, Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone: Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare; Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss, Though winning near the goal yet, do not grieve; She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss, For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu; And, happy melodist, unwearied, For ever piping songs for ever new; More happy love! more happy, happy love! For ever warm and still to be enjoy’d, For ever panting, and for ever young; All breathing human passion far above, That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy’d, A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.

Who are these coming to the sacrifice? To what green altar, O mysterious priest, Lead’st thou that heifer lowing at the skies, And all her silken flanks with garlands drest? What little town by river or sea shore, Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel, Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn? And, little town, thy streets for evermore Will silent be; and not a soul to tell Why thou art desolate, can e’er return.

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede Of marble men and maidens overwrought, With forest branches and the trodden weed; Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral! When old age shall this generation waste, Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” ❞When I look for a medium-specific narrative, I try to find one that roughly covers the whole work. In logical terms, one that justifies the work as a unit. Here’s one:

- The narrator questions a silent “thou.”

- The narrator associates the silent (“those unheard are sweeter”) with the eternal (“canst not leave […] nor ever,” “never, never”, “For ever,” etc.).

- The eternal is then associated with successions of “happy” and “love” (“Ah, happy, happy boughs!”, “happy melodist”, “More happy love! more happy, happy love!”).

- Finally, when the eternally silent (“Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought as doth eternity”) says something, it addresses the narrator’s questioning (“all ye need to know”) through structures of succession, reminiscent of the narrator’s successions of “happy:” “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

All the terms of the interpretations are reused and combined in different contexts. In (1), the “silent thou” is asked questions which are addressed in (4). The symmetric structure of the answer “beauty is truth, truth beauty” echoes the successions of the words happy and love in (3), but in a non-silent context which contrasts the silence in (1) and (2). A narrative thus emerges.

This narrative is medium-specific in the sense that it takes elements directly from the poem with almost no recourse to subjective interpretation. I say almost, because there is certainly some interpretation there. I skipped a lot of material. I skipped the details of the narrator’s questions. I didn’t mention the stanza structure or the rhyme schemes. Implicit in these oversights is an assessment that they didn’t strike me in any way as part of a significant poem-wide narrative. If you study the stanza structure or the poem’s themes, for example, as most scholars do, you get invariants rather than a narrative. But this choice, to prefer this poem-wide narrative over invariants, is already an act of subjective interpretation, even if, in the last analysis, I just highlighted certain passages of the poem.

Another way to deliver this interpretation would be to cook it a little bit, because it is a little too raw as it is. I could provide some commentary that would imply the feelings and value judgments that led me to this narrative. I could say this:

« John Keats thus makes us realize that our questioning is superfluous, in the sense that the answer was already contained in the narrator’s enthusiastic exuberance. The answer is the expression of overabundant joy, whether in the questioning itself (the streams of “what”) or in the passing observations (the almost creepy effusions about happiness and love), rather than a more conventional answer that would avoid T.S. Eliot’s criticism of the “grammatically meaningless” statement that “beauty is truth, truth beauty.” »

I will usually choose to stay away from this style of interpretation. Other “reconstructionists” may favor it. I personally like to address an audience that doesn’t need to be spoon-fed and will arrive at its own conclusions. In fact, I would argue that the raw interpretation doesn’t need any conclusion. The “episodes” of the narrative are interlinked with one another in such a way that the whole point is lost as soon as one tries to wrap things up in a conclusion.

Rediscovering intra-medium movement

Rediscovering intra-visuality. Restoring the primacy of the viewing angle.

Keeping the interpretation intra-medium is counter-intuitive to the critic. Content-bound communication is counter-intuitive to the people who receive it. “This painting represents the king”: this is a very natural statement to read, though it is hardly concerned with the objective content. If the reader of the statement sticks to what the interpretation actually communicates, and tries to visualize the painting through it, they could imagine a king sitting on a throne, a crown, or even a heraldic symbol. The visuals, along with all the non-visual facts (including the fact that this is the king), contribute to their own “story” separate from the visuals.

Such stories are independent of the king from a visual point of view—e.g., a figure standing between a curtain to his right and a pillar to his left—but it is assumed that these stories “merge” with the visuals and serve their meaning and, ultimately, value. They contrive a “viewerless world”:

to the extent that it is on the blackboard. And my effort is to surpass the concrete characteristics of the figure traced in chalk by not including its relation to me in my calculations any more than the thickness of the lines or the imperfection of the drawing.

Thus by the mere fact that there is a world, this world can not exist without a univocal orientation in relation to me. Idealism has rightly insisted on the fact that relation makes the world. But since idealism took its position on the ground of Newtonian science, it conceived this relation as a relation of reciprocity. Thus it attained only abstract concepts of pure exteriority, of action and reaction, etc., and due to this very fact it missed the world and succeeded only in making explicit the limiting concept of absolute objectivity. This concept in short amounted to that of a “desert world” or of “a world without men;” that is, to a contradiction, since it is through human reality that there is a world. Thus the concept of objectivity, which aimed at replacing the in-itself of dogmatic truth by a pure relation of reciprocal agreement between representations, is self-destructive if pushed to the limit.

❞In the viewerless world actually communicated by the interpretation, the king on the painting surface is not bidimensional. The work could very well be a sculpture without invalidating a single word of the interpretation, even if the king is described in great detail:

This could be Charles I in person. The painting, as actually communicated by the interpretation, captures a viewable object in a particular viewing angle (“to the right, a page proffers a helmet”) which doesn’t matter: the viewable object exists from every angle, and it exists independently of whether you view it or not. The focus is on the object, not the viewing. Painting-specific narratives restore the viewing angle.

Painting-specific narratives don’t innovate anything. It is subconsciously known that the concept of object is not necessary to all viewing experiences. They are first a product of abstraction and amnesia: the object only exists as an object insofar as I can move around it, maybe touch it, in any case imagine myself doing it, and empirically ascertaining that a volume underlies the visuals. By the time I have intuited the volume, it is typical for me to be oblivious of the sequence of bidimensional visuals that led to its representation, and I strongly suspect I am not alone. But the lines and shapes on the surface have their own properties, their own “story.” Of course, it is always healthy to remind oneself that the representation of volume and perspective on a flat surface is just an illusion, albeit a useful one.

The biased concept of uniqueness induced by false dichotomies of clichés versus non-clichés. Content-bound communication versus the non-cliché.

There is nothing trivial or objective in the assumption that all painters want to represent things. Picasso’s Mandolin Player might not be the obfuscated representation of a mandolin player. But even so, I will argue that the observer gains nothing from knowing that. What makes this assembly of geometrical patterns stand out, and not just be the equal of the sculpture of a mandolin player, if one were to believe the revelations of an analysis of this painting as a representation?

Sure, the overwhelming majority of painters actually wish for people to perceive their work as representations. But the point is not necessarily about the artist’s intention, but the potential of interpretation in general, and how people routinely put a ceiling on it—e.g., in abstract art, when the reviewer attempts, sometimes desperately, to figure out what may lurk behind the wall of abstract:

Three Musicians is an example of Picasso’s Cubist style. In Cubism, the subject of the artwork is transformed into a sequence of planes, lines, and arcs. Cubism has been described as an intellectual style because the artists analyzed the shapes of their subjects and reinvented them on the canvas. The viewer must reconstruct the subject and space of the work by comparing the different shapes and forms to determine what each one represents. Through this process, the viewer participates with the artist in making the artwork make sense.

❞The review is figure-centric. It tries to tell “where one musician starts and another stops,” because it has somehow decided that they were representations of actual musicians, with a certain idea of anatomical proportions. The analysis starts from a non-painting concept, the concept of figure, and projects it onto the visuals, effectively subordinating the medium to its preconceptions: the medium can only work toward what the viewer already knows. The cognitive experience is already prejudiced, even before the viewer has “reconstruct[ed] the subject and space of the work by comparing the different shapes and forms to determine what each one represents.”

In a preconception-free interpretation of visuals, there would be no place for such a thing as confusion and “not making sense.” Only bringing up one’s preconceptions does that. “It is hard to tell where one musician starts and another stops, because the shapes that create them intersect and overlap”: it is confusing in regard to the expectation of a certain kind of figures, but confusingly enough, the exact way shapes “intersect and overlap” doesn’t suffer any confusion. And the exact way they “intersect and overlap” may precisely be the whole point. If you look at the patches of blue, they induce a kind of dislocated figure: it has a chin borrowed from the white musician, eyes borrowed from the harlequin, and it has legs, too. This figure is a painting-specific recurrence of structure. It doesn’t encumber itself with likelihood.

The classical concept of figure belongs, with other concepts such as history, location, and meaning, to an implicit culture. This culture is oblivious to painting-specific narratives, favoring instead cultural clichés. The cultural clichés are anticipated, to the point that non-clichés are only recognized where we are looking for the cultural clichés. In Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors, Slavoj Žižek calls the bizarre anamorphic skull in the center “the blot”: an inaccessible, obscure object of desire.

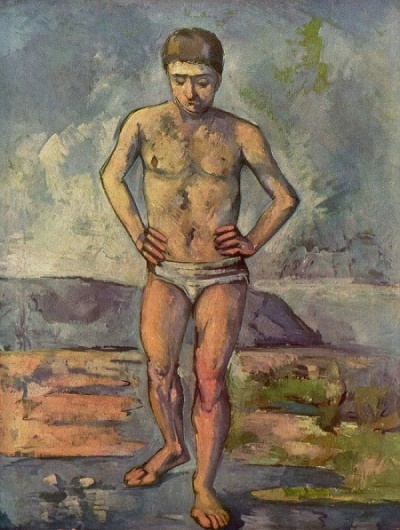

The blot is most unusual, but isn’t it also unusual that in Cézanne’s The Nude Bather, an expanse of mountain in the background runs parallel to the flat ground and slopes off at a certain angle?

In Picasso’s Life, isn’t it unusual that a woman and a man stare at each other, while a child, clinging to the woman, looks away? The blot in The Ambassadors is a kind of figure, and is instantly acknowledged through contrast with a certain preconception of painting. But in the painting-specific narrative, the fact that it doesn’t play more of a role than any similarly shaped figure would—say, a quill slanting at the same angle—reveals the interpretive bias, in both the cliché and the non-cliché. And the acknowledgement of this bias makes even the most mundane scene an ever-fresh source of possibilities. What could not have the potential for painting-specific narratives? Cézanne found them in vases, fruits, and silver cutlery. Anybody could find them in the bricks of a prison cell, or in the racks of vegetables in a supermarket.

Flatness in Modernist painting was, in the beginning, a non-cliché that fed off the clichés. For Clement Greenberg, the “purity” of “w:medium specificity” is the affirmation of its independence from the figurative:

It quickly emerged that the unique and proper area of competence of each art coincided with all that was unique in the nature of its medium. The task of self-criticism became to eliminate from the specific effects of each art any and every effect that might conceivably be borrowed from or by the medium of any other art. Thus would each art be rendered “pure,” and in its “purity” find the guarantee of its standards of quality as well as of its independence. “Purity” meant self-definition, and the enterprise of self-criticism in the arts became one of self-definition with a vengeance.

Realistic, naturalistic art had dissembled the medium, using art to conceal art; Modernism used art to call attention to art. The limitations that constitute the medium of painting—the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment—were treated by the Old Masters as negative factors that could be acknowledged only implicitly or indirectly. Under Modernism these same limitations came to be regarded as positive factors, and were acknowledged openly. Manet’s became the first Modernist pictures by virtue of the frankness with which they declared the flat surfaces on which they were painted. The Impressionists, in Manet’s wake, abjured underpainting and glazes, to leave the eye under no doubt as to the fact that the colors they used were made of paint that came from tubes or pots. Cézanne sacrificed verisimilitude, or correctness, in order to fit his drawing and design more explicitly to the rectangular shape of the canvas.

❞But this purity co-exists with non-Modernism, just as we saw in Picasso’s particular style of “figure”: structure, through placement and color rather than volume, fulfills the Modernist part, and the figurative quality fulfills the non-Modernist part. Greenberg himself admits as much:

And I cannot insist enough that Modernism has never meant, and does not mean now, anything like a break with the past. It may mean a devolution, an unraveling, of tradition, but it also means its further evolution. Modernist art continues the past without gap or break, and wherever it may end up it will never cease being intelligible in terms of the past. […]

❞This attachment to tradition does not prevent “purity” from serving as a “just, good, and relevant reason for appreciating masters”:

Also the Postscript, in which Greenberg defends himself from “advocating” pure art, correlates purity with the “very best art of the last hundred-odd years”:

This “usefulness” of “pure” art helped propel the “best” art over the lesser art, but there’s a caveat. The claim that the best art comes about by emphasizing “the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment” doesn’t actually communicate any demarcation between “best” and lesser art; Greenberg certainly came across pure paintings he found more pointless than others, unless he is to pure paintings what Marilyn Burns of Texas Chainsaw Massacre fame is to horror movies, according to this interview:

MB: They’re all favorites. I used to watch horror films on Saturday mornings. I like them all. I’m like you guys. You've got more films on your website than I know! And I thought I used to have the category down…

TT: Thank you! Which genre do you enjoy the most?

MB: I like it all. I like mysteries, suspense, horror, comedy, historical… I run the whole gamut. It’s all wonderful.

TT: Have a favorite movie?

MB: I don’t know… I can’t name favorites because I like them all.

❞Purity isn’t enough of a criterion to demarcate art—at least it hasn’t been for a while, because it’s become a trope—but it contrasts nicely with a cultural bias for figurative painting as a cliché. As soon as both pure and non-pure paintings became equally accepted by the public, purity revealed itself to be too coarse as a criterion. In fact, non-pure paintings, even photographs, can be interpreted in terms of “the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment.” I could also “purify” any painting by overlaying it with solid colors, and I certainly wouldn’t expect Greenberg to hang it up there with his “best art.” Reciprocally, a priori non-pure art, such as photographs, can be interpreted through a purity lens. This photograph from Jay Maisel, Damsels wearing face packs posing before panels, illustrates this:

The mise-en-scène actually divides the surface around convex shapes enveloping both women. The separation is further emphasized by the panels in the background. It’s particularly formal.

To be more accurate, the panels lead to the right, and point “outside” the painting. This confers a peculiar quality to the left arm and hand of the woman to the right. The left hand follows the convex shape (dashed line around her head):

but the left arm “moves” it in the direction sketched by the contour of the lockers. It is a kind of mutant motif.

We know the left arm and the left hand belong to the same woman. This is the figurative part. But its pure formality also denotes a medium-specific narrative. It isn’t a mere matter of opposition between purity and non-purity. The described medium-specific narrative very specifically relies on the recognizable “figure” of the left hand connecting to the left arm, as emphasized by the uniform whiteness of the skin.

The interpretation of medium-specific narratives stresses uniqueness across both the flat and the non-flat. It doesn’t rely on a general theory of art, nor on a theory of the medium such as “medium purity.” It isn’t a theory of this “very best art of the last hundred-odd years,” either. It is a this here interpreted-medium-specific interpretation. This content-bound communication does not need to reference clichés, even indirectly, in order to produce non-clichés, unlike parodies and shock value at their most obvious. In a way, this echoes the sentiment of certain authors like Deleuze and Guattari, who not only criticize the “order of the signifying and the figure,” but also its opposite, the “pure figural” as a “transgression...that remain[s] secondary nonetheless,” that is, secondary to the “schizophreny as process”:

[…] dans le rêve, Lyotard montre dans de très belles pages que ce qui travaille n’est pas le signifiant, mais un figural en dessous, faisant surgir des configurations d’images qui se servent des mots, les font couler et les coupent suivant des flux et des points qui ne sont pas linguistiques, en ne dépendent pas du signifiant ni de ses éléments réglés. Partout donc Lyotard renverse l’ordre du signifiant et de la figure. Ce ne sont pas les figures qui dépendent du signifiant et de ses effets, c’est la chaîne signifiante qui dépend des effets figuraux, faite elle-même de signes asignifiants, écrasant les signifiants comme les signifiés, traîtant les mots comme des choses, fabriquant de nouvelles unités, faisant avec des figures non figuratives des configurations d’images qui se font et se défont. […] L’élément du figural pur, la “figure-matrice,” Lyotard la nomme bien désir, qui nous conduit aux portes de la schizophrénie comme processus. Mais d’où vient pourtant l’impression du lecteur que Lyotard n’a de cesse d’arrêter le processus, et de rabattre les schizes sur les rivages qu’il vient de quitter, territoires codés ou surcodés, espaces et structures, 'où ils ne font plus qu’apporter des “trangressions,” des troubles et des déformations malgré tout secondaires, au lieu de former et d’emporter plus loin les machines désirantes qui s’opposent aux structures, les intensités qui s’opposent aux espaces ? C’est que, malgré sa tentative de lier le désir à un oui fondamental, Lyotard réintroduit le manque et l’absence dans le désir, le maintient sous la loi de castration au risque de ramener avec elle tout le signifiant, et découvre la matrice de la figure dans le fantasme, le simple fantasme qui vient occulter la production désirante, tout le désir comme production effective.

❞Rediscovering graphical narration. A comics-specific narrative from Goossens’ Touti and his exhaust pipe.

When it comes to single images, it seems weird that one may speak of a narrative, much less an epic one. But this weirdness is a result of an amnesic way of looking at images. For if one would only be so inclined as to take the placement of a house, the branch of a tree, or the direction of the aggressive strokes shaping a loaf of bread in a Cezanne still life to be as relevant to the image as a death is to a crime novel, one would immediately look at the potential foundation of a “graphical story” with multiple heretofore ignored “graphical events.” The events would just be the actions of our visual experience: our gaze moving a virtual pencil across the canvas. Each stop, each change of direction would be recorded into a medium-specific narrative, just like events are recorded into the timeline of a regular novel.

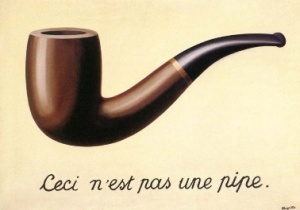

Daniel Goossens’ comic Touti and his exhaust pipe nicely illustrates the difference between graphical and event-based story-telling. Comics feature two pedagogical advantages over traditional painting: their naturally narrative format, and text. Captions can narrate events just like event-based story-telling, but they can also introduce a self-aware “break-the-fourth-wall” voice that can force the reader to rethink their relationship to the visual medium, often with a comical effect not unlike René Magritte’s This is not a pipe.

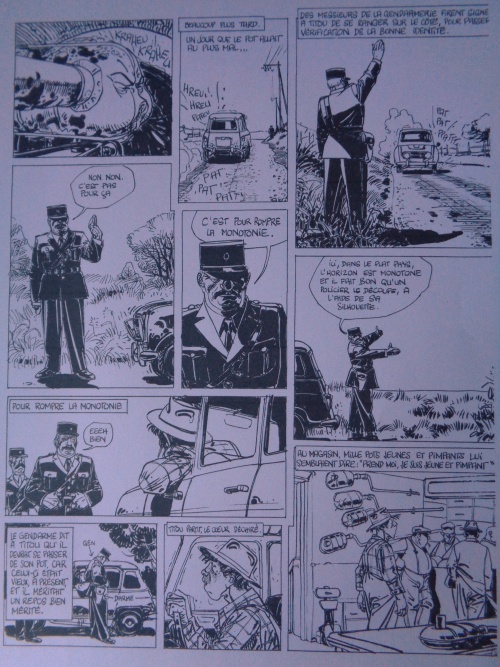

Here’s a page from Goossens’ comics:

The policeman seems to signal Touti to pull over because of the malfunctioning exhaust pipe, but he corrects the narrator: “No, it’s not for that. It’s to interrupt the monotony. Here, in the flat lands, the horizon is monotonous, and it is fitting that a policeman cuts through it using his silhouette.”

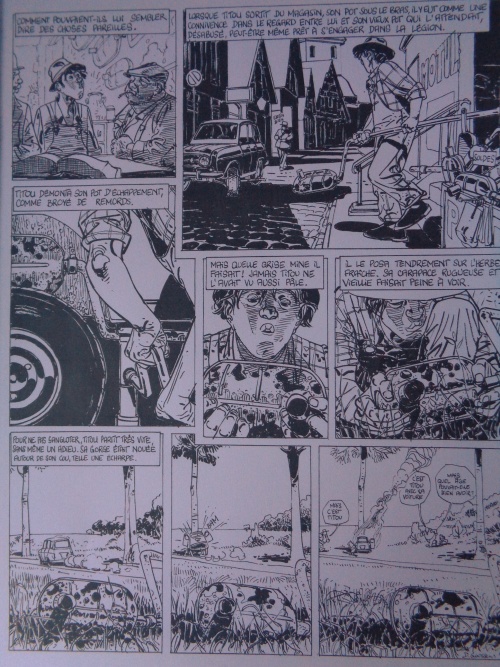

His speech comically emphasizes his verticality rather than the usual concept of “officer of the Law.” The story then builds up toward a car crash:

Significantly enough, the car runs into a tree “cutting through the horizon,” in a reminiscence of the vertical officer. A “comics-specific” narrative thus emerges.

The interpretation changes altogether when one switches to an event-based viewpoint. The policeman’s appearance is a casual event in the timeline. When all is said and done, all he did was advise Touti to get his exhaust pipe changed. The story kind of expresses the “irony of fate:” at the time of the crash, the car had just been repaired, and to add insult to injury, the tragic turn of events came about due to the advice of the policeman. This interpretation is independent from the graphical representation: seeing the crash from above, instead of having the tree “cut through the horizon,” wouldn't change anything. It would represent a graphically different, but story-wise identical, collision.

Rediscovering intra-textuality

Staying inside the text medium: the New Criticism movement. The cliché/non-cliché bias.

Traditionally, interpretation treats prose differently from poetry, poetry differently from w:sound poetry, etc. We naturally expect interpretations of poems to be more medium-specific than interpretations of novels, if only because they will be more attentive to the details of structure, rhythm and sound, all poem-specific material. Yet, this couldn’t help but stimulate reactionary movements such as the New Criticism:

Just as the “blot” forced the path of interpretation in visual art, literary content can force the interpreter’s hand. Sound poetry, for example, has a tendency to complicate the English translator’s life because their interpretation doesn’t approximate the content nearly enough:

But just as the “blot” showed a cliché/non-cliché bias for the figure, sound becomes an interpretive bias as soon as one ignores it in other places because we don’t expect sound to matter there. Such is the case for the final lines of Ode on a Grecian Urn, whose sound structure—“Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know”—went largely unattended by the majority of academics who chose instead to debate about the meaning and who truly spoke to whom: “poet to reader, urn to reader, poet to urn, poet to figures on the urn?”

The question of scale: the medium-specific micro-narratives in contemporary culture.

Medium-specific narratives in literature are nothing new. For example, reasoning fallacies offer various forms of medium-specific narratives. What they lack in reality, scientific reliability, and applicability, they gain by being amusing, entertaining, witty, comical, interesting, artful, and limitless. Syllogistic fallacies could very well be described as the “patterns of resolved stresses” that the New Criticism used to describe poetry. Stress accumulates with each additional premise, and the conclusion works and resolves the stress mostly because it sounds good:

- All inhabitants of other planets drink water.

- All Martians are inhabitants of another planet.

- Therefore, some Martians drink water.

The symmetric quality of the transition from “All inhabitants of other planets drink water” to “Therefore, some Martians drink water,” in both sentence structure and word usage, plays no small part in the efficiency of the argumentation. Rewriting the conclusion into a less symmetric form would go a long way toward exposing the fallacy:

- All inhabitants of other planets drink water.

- All Martians are inhabitants of another planet.

- Therefore, among all the beings who drink water, there must exist at least one Martian.

Consider another example:

- All students have been young.

- My grandfather has been young.

- Therefore, my grandfather is a student.

The fallacy relies on resonance, both semantic and structural. Should the premises be very distinct from each other, fewer would be fooled into believing the conclusion. The following rewrite would be far less convincing:

- All political leaders, doctors, and students have been young.

- My grandfather has been young.

- So he is a student.

In comparison, immaculate rational reasoning is obvious, down-to-earth, tautological, tedious.

- All political leaders, doctors, and students have been young.

- My grandfather has been young.

- He may have been a political leader, a doctor, and/or a student, but it is not necessary.

Fallacies are not exclusive to well-known syllogisms that fit into 3 sentences. They mostly occur in prose, most unassumingly in science literature. The reader doesn’t always need a science degree in order to perceive the fallaciousness, because the fallacy, as a medium-specific narrative, is expressed by the text itself, in a self-contained way. The requirement is that the reader read the text narratively.

Of course, not all of science is equal. Compared to axiomatic science, empirical science as a collection of universal laws (“the action is always equal to the reaction”) is more entertaining, whether because of the leaps of faith that, as Hume pointed out, are required to elevate experimental observations to universal statements, or because of the “wishful-thinking” justifications of their well-foundedness, especially in the fields of applied logic and mathematics. For example, in The Logic of Scientific Discovery, Popper refutes the argument that his concept of “degree of corroboration of probability hypotheses” is reducible to traditional probability:

p(x) = 1/6; p(y) = 5/6; p(z) = 1/2.

Moreover, we have the following relative probabilities:

p(x, z) = 1/3; p(y, z) = 2/3.

We see that x is supported by the information z, for z raises the probability of x from 1/6 to 2/6 = 1/3. We also see that y is undermined by z, for z lowers the probability of y by the same amount from 5/6 to 4/6 = 2/3. Nevertheless, we have p(x, z) < p(y, z). This example proves the following theorem:

(5) There exist statements, x, y, and z, which satisfy the formula,

p(x, z) > p(x) & p(y, z) < p(y) & p(x, z) < p(y, z).

Obviously, we may replace here ‘p(y, z) < p(y)’ by the weaker ‘p(y, z) ≤ p(y)’.

This theorem is, of course, far from being paradoxical. And the same holds for its corollary (6) which we obtain by substituting for ‘p(x, z) > p(x)’ and ‘p(y, z) ≤ p(y)’ the expressions ‘Co(x, z)’ and ‘¬Co(y, z)’—that is to say ‘non-Co(y, z)’—respectively, in accordance with formula (1) above:

(6) There exist statements x, y and z which satisfy the formula

Co(x, z) & ¬Co(y, z) & p(x, z) < p(y, z).

Like (5), theorem (6) expresses a fact we have established by our example: that x may be supported by z, and y undermined by z, and that nevertheless x, given z, may be less probable than y, given z. There at once arises, however, a clear self-contradiction if we now identify in (6) degree of confirmation C(a, b) and probability p(a, b). In other words, the formula

(**) Co(x, z) & ¬Co(y, z) & C(x, z) < C(y, z)

(that is, ‘z confirms x but not y, yet z also confirms x to a lesser degree than y’) is clearly self-contradictory.

Thus we have proved that the identification of degree of corroboration or confirmation with probability (and even with likelihood) is absurd on both formal and intuitive grounds: it leads to self-contradiction. ❞However, formula (**) is not necessarily self-contradictory, both on intuitive and mathematical grounds. Let’s see why.

Popper provides a metaphor for formula (**): “x has the property P (for example, the property ‘warm’) and y has not the property P and y has the property P in a higher degree than x (for example, y is warmer than x).” Put like this, (**) certainly seems self-contradictory.

But Popper is misleading when he equates C(x, z) < C(y, z) to “y has the property P in a higher degree than x,” because by definition, this would mean we have “p(y, z) > p(y) to a higher degree than p(x, z) > p(x).” We are comparing the degree of difference between 2 statements relative to different references, namely p(x) and p(y). I can say that Alice is taller than Bob in a higher degree than Cedric is taller than David, but it’s not contradictory to say that Cedric is taller than Alice.

So a more accurate metaphor for P would be “warmer” rather than just “warm,” with an important emphasis on warmer than what. Obviously, if one makes x warmer and y cooler, y can still be warmer than x because it was very hot to start with, so having C(x, z) < C(y, z) doesn’t seem contradictory anymore.

Such losses in metaphor share with syllogisms the same propensity for erasing structural relationships by means of “literary devices,” such as the shortcut from “warmer” to “warm.” They form an infinity of unique narratives when translating back and forth between informal and formal language. Popper himself debunks someone else’s definition that belongs to the wide spectrum of sensationalist interpretations of numbers and mathematical/physics formulas that theoretical physics is especially fond of (the many-worlds interpretation, Schrödinger’s cat, and time dilation being a small sample):

of the (discontinuous) reduction of the wave packet’. Some leading physicists told me in 1934 that they agreed with my trivial solution, yet the problem still plays a most bewildering role in the discussion of the quantum theory, after more than twenty years.]

Imagine a semi-translucent mirror, i.e. a mirror which reflects part of the light, and lets part of it through. The formally singular probability that one given photon (or light quantum) passes through the mirror, αPk(β), may be taken to be equal to the probability that it will be reflected; we therefore have

\(_αP_k(β) = _αP_k(\bar{β}) = {1 \over 2}\)

This probability estimate, as we know, is defined by objective statistical probabilities; that is to say, it is equivalent to the hypothesis that one half of a given class α of light quanta will pass through the mirror whilst the other half will be reflected. Now let a photon k fall upon the mirror; and let it next be experimentally ascertained that this photon has been reflected: then the probabilities seem to change suddenly, as it were, and discontinuously. It is as though before the experiment they had both been equal to \({1 \over 2}\), while after the fact of the reflection became known, they had suddenly turned into 0 and to 1, respectively. It is plain that this example is really the same as that given in section 71. [That is to say, the probabilities ‘change’ only in so far as α is replaced by β. Thus \(_αP(β)\) remains unchanged \({1 \over 2}\); but \(_\bar{β}P(β)\), of course, equals 0, just as \(_βP(β)\) equals 1.] And it hardly helps to clarify the situation if this experiment is described, as by Heisenberg, in such terms as the following: ‘By the experiment [i.e. the measurement by which we find the reflected photon], a kind of physical action (a reduction of wave packets) is exerted from the place where the reflected half of the wave packet is found upon another place—as distant as we choose—where the other half of the packet just happens to be’; a description to which he adds:

‘this physical action is one which spreads with super-luminal velocity.’ This is unhelpful since our original probabilities, \(_αP_k(β)\) and \(_αP_k(\bar{β})\), remain equal to \({1 \over 2}\). All that has happened is the choice of a new reference class—β or \(\bar{β}\), instead of α—a choice strongly suggested to us by the result of the experiment, i.e. by the information \(k \in β\) or \(k \in \bar{β}\), respectively. Saying of the logical consequences of this choice (or, perhaps, of the logical consequences of this information) that they ‘spread with super-luminal velocity’ is about as helpful as saying that twice two turns with super-luminal velocity into four. A further remark of Heisenberg’s, to the effect that this kind of propagation of a physical action cannot be used to transmit signals, though true, hardly improves matters. ❞Most fallacies share the liberal use of definitions, but their form and scale vary from one fallacy to the other, ranging from style figures to elaborate theses.

Non-fiction literature

Prerequisite to rediscovery: stoicism in the face of contradictions, errors, dislikes, dichotomies. Pushing the concept of open-mindedness outside immediate taste to discover other structures.

Medium-specific narratives put the emphasis on the usage of sentences, arguments, thoughts, etc., rather than on their individual choice and value, as the prevailing mentality would have it. But a medium-specific narrative is only a part of the text, and the text doesn’t tell you how you should react to it. You have absolute free rein to overlook the medium-specific narrative aspect.

This also goes for the author of fallacies. They can freely overlook their “shortcomings”—I put that in quotes, because fallacies may be inconsequential, or even work out for the best. Most would agree that contradictions in a scientific theory should be cause enough to ditch it. Yet, the thesis carries no shame. The text medium outlasts the intolerant reader. Despite all the possible contradictions, the author’s text continues. It weaves a tissue of contradictions, contradictions that break conventions, “don’t make sense,” or are so full of involuntary errors that even the author sincerely repudiates their own work. It’s just like science fiction: it doesn’t matter.

When we ditch a logic system because it is self-contradictory, we do so for the same reason we ditch any other self-contradictory logic system: a single contradiction puts the whole system in jeopardy, since any proposition and its contrary could be logically derived from it. Yet the text that describes a self-contradictory logic system only explores a very small subset of the infinite set of possible texts, and it does so in its own way. The confusion in Popper, as quoted above, is not only the confusion between the comparative and absolute forms, e.g., between “warm” and “warmer,” between “confirmed” and “confirmed to a higher degree.” There is a very medium-specific narrative that makes the confusion the more unique. Popper makes the formula “Co(x, z) & ¬Co(y, z) & p(x, z) < p(y, z)” appear all the more self-contradictory because he first defined p(x, z) > p(x) as Co(x, z) (“z confirms x to a higher degree”), and because Co(x, z) is easier to mistake with the absolute form “x confirms z.” This is a case where the fallacy in the mix of formal and natural discourse highly depends on the order of presentation: first use a form to make some point, then introduce an abbreviation, then use an illicit definition of this point to make some other point—this is a medium-specific narrative.

The uniqueness is not literal. Of course, one could easily have declared that the sentences used by Popper are unique. I am not stressing so much literal uniqueness—which most would agree is pointless—as a uniqueness of structure. Multiple medium-specific narratives coexist in the same text, and a reader with sensibilities different from mine could emphasize another narrative.

The contradictions kind of “stop” the text. Not that one is forced to stop reading. The usual way people reconcile contradictions with the undisturbed flow of the text is by conceiving them in a mosaic of good and bad points. In other words, we fill the “holes” of the fallacies with the holes that make up the mosaic.

The stopping does not only apply to contradictions, but also to a whole repertoire of attention-grabbers: writing style, subject matter… anything, really, that may lead to something as innocuous-looking as liking or disliking. In music, we may stop listening to a death metal song after just a few notes just because the Cookie Monster vocals put us off. We may not finish a book because we disagree with its main points, or find it hard to care about the characters, or are just getting bored by the first pages. But even a boring start may lead to a not-so-boring end. This applies to other media as well. In visual art, contradictions take the form of confusion, e.g., confusion between the mundane and the sublime, the lively and the still, the planar and the perspective, the colorful and the monochromatic, the imitative and the non-imitative, etc. We may find something bad, distasteful, even repulsive in a movie. Yet the movie continues unhindered. We are the Jean-François Lyotard that Deleuze and Guattari criticized for “never ceasing to stop the process, to recall the schizes to the shores that he just left, coded or overcoded territories, spaces and structures, where they only bring ‘transgressions,’ disorders and distortions that remain secondary nonetheless.”

You might get the notion that my discourse echoes the good old plea for open-mindedness. However, when people beg for open-mindedness, it is usually either in the hope of changing people’s minds or with the mindset that others should have better tastes. In effect, these people are being criticized for their tastes, albeit in a politically correct way. “Be open-minded, what you don’t like is actually very good, no matter how you feel about it.” On the contrary, I absolutely don’t intend to change people’s minds about what they don’t like, especially if “what they don’t like” is a product of private interpretation. What people didn’t like, they’ll still dislike, whatever it is they don’t like. I only speak from the perspective of the medium-specific narrative, which might very well be different from “what they don’t like,” although both are about the same content. Metaphorically, feces are distasteful and repulsive, a useless by-product (who would complain if we never had to defecate ever again?), yet this doesn’t take anything away from the elegance of a rural ecosystem where one can defecate in the open and let Nature make it disappear in a matter of minutes, at least when compared to our sewage systems.

Stoicism in the conventionalist interpretation of scientific literature.

The conventionalist interpretation of an axiomatic system consists in viewing the fundamental concepts as implicit definitions:

(i) If the axioms are regarded as conventions then they tie down the use or meaning of the fundamental ideas (or primitive terms, or concepts) which the axioms introduce; they determine what can and what cannot be said about these fundamental ideas. Sometimes the axioms are described as ‘implicit definitions’ of the ideas which they introduce. This view can perhaps be elucidated by means of an analogy between an axiomatic system and a (consistent and soluble) system of equations.

The admissible values of the ‘unknowns’ (or variables) which appear in a system of equations are in some way or other determined by it. Even if the system of equations does not suffice for a unique solution, it does not allow every conceivable combination of values to be substituted for the ‘unknowns’ (variables). Rather, the system of equations characterizes certain combinations of values or value-systems as admissible, and others as inadmissible; it distinguishes the class of admissible value systems from the class of inadmissible value systems. In a similar way, systems of concepts can be distinguished as admissible or as inadmissible by means of what might be called a ‘statement-equation’. A statement-equation is obtained from a propositional function or statement-function; this is an incomplete statement, in which one or more ‘blanks’ occur. Two examples of such propositional functions or statement functions are: ‘An isotope of the element x has the atomic weight 65’; or ‘x + y = 12’. Every such statement-function is transformed into a statement by the substitution of certain values for the blanks, x and y. The resulting statement will be either true or false, according to the values (or combination of values) substituted. Thus, in the first example, substitution of the word ‘copper’ or ‘zinc’ for ‘x’ yields a true statement, while other substitutions yield false ones. Now what I call a ‘statement-equation’ is obtained if we decide, with respect to some statement- function, to admit only such values for substitution as turn this function into a true statement. By means of this statement-equation a definite class of admissible value-systems is defined, namely the class of those which satisfy it. The analogy with a mathematical equation is clear. If our second example is interpreted, not as a statement-function

but as a statement-equation, then it becomes an equation in the ordinary (mathematical) sense. ❞As Popper stresses, the conventionalist view, although unacceptable for some purposes, is unattackable: isn’t the conventionalist at liberty to consider a definition as he pleases? In fact, this view is unacceptable in Popper’s sense precisely because it makes any theoretical system unattackable. If a theory in geometry contains an axiom that states that a geometrical point has an area, the conventionalist view does not claim that it is an actual observation or anything measurable. It is some definition of the point—or more accurately, the word “point.” Definition is only the arbitrary start to an arbitrarily large system. The focus is not the definition itself, but what one makes of it: something that can be aesthetical, witty, comical, or even scientifically useful. What if one invents a geometry where Euclid’s w:parallel postulate does not hold: “If a straight line falling on two straight lines make the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which are the angles less than the two right angles.” In terms of usage, one could construe this as peek into the field of non-Euclidean geometry, elliptic and hyperbolic geometries, and w:curved space, where basic theorems like the Pythagorean theorem or the triangle postulate—“The sum of the angles in every triangle is 180°”—do not hold anymore. This, in turn, helps describe the transition from special to general relativity in modern physics:

For some, this would be cause enough for ditching a manual of modern physics. Non-Euclidean geometry is neither intuitive, nor observable, nor simple—for what would be a space where “parallel” lines intersect? However, in terms of usage, the non-intuitive may lead to the prediction of observable effects. And it can also increase simplicity:

But this implies that one first accepts the definitions as they are, rather than harping on them and potentially missing the point, such as the ability to make predictions or to construct a unified theory with practical applications.

Rediscovering philosophy

A philosophical work is not usually considered art. However, as a text, it has text-specific narratives. In a field where most problems come from the misalignment of definitions between opinionated people, the interpretation of a text-specific narrative has the tastefulness not to descend into the spiral of surmising with one’s definitions to prove one’s point, but instead reveals the uniqueness of the misalignment. In fact, a point can be made that without its false problems of misalignment, philosophy would be boring. Its arguments would either be perfectly logical to the point of tautology, or verge on the mystic. For example, the talk about objectivity and reality would dumb down to the assertion that “objects” are external to me in the sense of their spatial relationship to my body. Granted, it wouldn’t be as interesting as speculating of an external reality “in-itself,” lying outside my perception and even the possibility of perception or cognition. This is the paradigm of the philosopher (here Descartes) who creates “interesting” false problems that keep the next generations of philosophers busy. Ironically, these critics, being philosophers themselves, can’t help but make what is bred in the bone come out in the flesh. So there are some cases where the critic is spot-on, but in their own philosophy walks into pretty much the same traps as their peers—cf. my reconstructions of Schopenhauer tackling Leibniz and Hegel.

Definition misalignment is often supported by selective amnesia. For example, the author presupposes A to prove some statement (in favor of the author’s thesis), then presupposes the antithesis of A (amnesia of the thesis of A) to prove another statement. Amnesia can happen at all scales. At the phrase and paragraph level, amnesia is a traditional literary style figure. At the phrase level, it is generally acknowledged by literary analysis. As the scale level goes up, analysis loses granularity and uniqueness, most significantly at the work level.

At the phrase level, take the infamous “DLC fiasco,” where a game editor, Capcom, delivers a game disc on the Playstation with locked content that can be unlocked for a fee. Then came the voices of protest:

But if “you just paid for a license,” then Capcom doesn’t revoke anything you paid for by locking away the content, since the lock is part of the license. Of course, this doesn’t mean you don’t have the right to be discontent, but don’t expect to be any more legit than someone protesting that a car should come with all the options because the manufacturer has the keys to unlock the warehouse.

At the paragraph level, in Anti-Œdipus Deleuze and Guattari take a bite at Freud’s Œdipus complex. In particular, they argue that incest is impossible in the system in which it exists:

[…] les noms ,les appellations ne désignent plus des étatts intensifs, mais des personnes discernables. La discernabilité se pose sur la sœur, la mère comme épouses interdites. C’est que les personnes , avec les noms qui les désignent maintenant, ne préexistent pas aux interdits qui les constituent comme telles. Mère et sœur ne préexistent pas à leur interdiction comme épouses. Robert Jaulin le dit très bien: “Le discours mythique a pour thème le passage de l’indifférence à l’inceste à sa prohibition : implicite ou explicite, ce thème est sous-jacent à tous les mythes ; il est donc une propriété formelle de ce langage.” De l’inceste, il faut conclure à la lettre qu’il n’existe pas, ne peut pas exister. L’inceste, on est toujours en deçà, dans une série d’intensités qui ignore les personnes discernables ; ou bien au-delà, dans une extension qui les reconnaît, qui les constitue, mais qui ne les constitue pas sans les rendre impossibles comme partenaires sexuels. L’inceste, on ne peut le faire qu’à la suite d’une série de substitutions qui nous en éloigne toujours, c’est-à-dire avec une personne qui ne vaut pour la mère ou la sœur qu’à force de ne pas l’être : celle qui est discernable comme épouse possible.

❞“Prohibited spouse” was sneakily replaced by “impossible spouse,” so that, indeed, it is now impossible to commit incest, since, by definition, incest now identifies mother and sister as impossible.

In The Capital, Karl Marx manages to (1) up the value of the laborer in the process of production, then (2) represent him as a value-less victim “from the social point of view.” In the following, notice how a “sine qua non condition” becomes an “appendage of capital” as well as a “mere moment.”

[…]

From a social point of view, therefore, the working class, even when not directly engaged in the labour process, is just as much an appendage of capital as the ordinary instruments of labour. Even its individual consumption is, within certain limits, a mere moment in the process of production. That process, however, takes good care to prevent these self-conscious instruments from leaving it in the lurch, for it removes their product, as fast as it is made, from their pole to the opposite pole of capital.

❞In the same line of thinking, Marx demonstrates the laborer’s “once again direct” contribution to increased production:

Here the “advance of [more seed and manure] is made,” but in the concluding phrase of the paragraph, the increased production now occurs “without the intervention of any new capital.”

Gottlob Frege’s the Foundations of Arithmetic offers a good example of book-level amnesia. It enters a particular category, that of not keeping a promise made at the beginning of a book. The book starts with this:

Now, let’s teleport to the end of the book and examine Frege’s own definition of the “number”:

Therefore Frege’s definition relies on an “indefinite” (the “extension of concept”) “without stating which thing it is”, and thus ends up doing what he warned not to do. The narrative is the knowledge which “honors” such book-level processes (whether they are unintended is beyond the point).

Rediscovering repetition and order

The concepts of repetition and order have a strong cultural recognition. The trope of the story loop, where the ending loops back to the beginning, such as in Lewis Carrol’s Alice In Wonderland, is well-acknowledged. In poetry, repetition of sound and structure has been thoroughly studied. In mainstream music, people expect a chorus to repeat.

Such tropes can be seen as global invariants. They help to categorize the whole work, and they abstract time away. If a critic categorizes a movie as neo-noir, then you can expect a certain tone, certain types of characters, and stories. Even though they are presented on a timeline, they become features of a finished, non-evolving product; they become constants. The apparent lack of temporality is most striking in music, arguably the temporal medium par excellence. The reader of a book can read the description of a scene and paint the scene in his head. Although the reading itself is temporal, the scene it renders can be static and atemporal. In a way, the reader can pretend the reading experience was atemporal. It doesn’t matter whether the reader reads “a blue sky was seen” or “the sky I saw was blue.” Although the order of the words, their temporality in the reader’s frame of reference, change, they usually mean the same to the interpreter who projects them into a still image. In music, atemporality is somewhat more difficult to pretend, because music imposes a tempo on the listener. One could conceive that a reader with photographic memory can “read” pages in the blink of an eye. By contrast, music only reveals itself at its own pace. Yet, in classical music, one is used to designate the pieces of a concerto or symphony by a “blanket tempo.” A Vivaldi concerto, for example, is often divided into 3 movements identified by the tempo, usually: Allegro (fast), Largo (slow), then Allegro (fast). Each movement’s “velocity” is never as strictly uniform as the tempo would suggest. It’s like velocity had been made into an atemporal category by abstracting away the velocity changes inside the same movement. Similarly, some people identify and categorize a piece of music by its harmonic scale.

Such blanket concepts are a product of narrative features becoming identifiable and well-known invariants. However, the more unique the narrative, the less blanketable it becomes. The aforementioned medium-specific narrative of Ode to a Grecian Urn doesn’t have (yet) a blanket term because it is fairly specific, although each step of the narrative is individually unremarkable. Some steps are clearly about repetition, but through the filter of a specific narrative. As a consequence of specificity, I can only communicate the whole narrative by going through all 4 steps of the narrative in order, recreating the temporal structures therein.

Yet, blanket concepts sometimes are declared as attempts to capture uniqueness. I was once in a music theory class where Chopin’s music was characterized by its “question/answer structures.” That is, the phrases played in succession on the piano almost sound like a dialogue between different instruments. This sounds on point. But, come to think of it, one can actually say the same thing of any piece of music. It’s not only the phrases that engage into a dialogue. A phrase can usually be divided into segments that compete to express their individual voices. Division is recursive and can reach down to the level where notes compete against each other. The levels of division don’t have to be mutually exclusive; they actually coexist. Notes are particular cases of segments that enter into the composition of larger segments and phrases, and the particular multidimensional way in which the dialogues take life in some medium-specific narrative is just part of a discovery.

Rediscovering composite media

Intra-medium narrative versus composite media such as songs. “Medium pairing” as a value judgment versus the intra-heteromedium narrative.

The notions of medium specificity and of being intra-medium bring up the question “Which medium?” A composite medium is a combination of layers, e.g., a song can be seen as lyrics on top of an instrumental. I will use the term “heteromedium” for such media, and “intra-heteromedium” to qualify an interpretation limited to the content of a heteromedium.

To be perfectly accurate, what most would consider to be a monomedium is necessarily composite. Text has sound, syntax, semantics, structure, etc. Sound has tonality, rhythm, phrasing, texture, etc. Furthermore, not one such property can be made into a “truly” one-dimensional medium. Tonality cannot exist in a vacuum, just like color cannot exist without some sense of shape, or a line without some sense of thickness. Even so, we never pay attention to everything. It is not uncommon to ignore the lyrics in a song. Other parts of the medium may be deemed unessential depending on the listener. When listening to a heavy metal song, I will usually ignore the obligatory guitar solo every other chorus, the elaborate drum fills, the redundant bass lines, etc.

Despite the fundamental heterogeneity of heteromedia, there has always been a sense of medium unity which has overpowered the other aspects of heteromedium interpretation. It is not uncommon to hear about how well lyrics match the music, the music the movie, the dancing the music, etc. The question as to how well the layers match is typically indicative of a value judgment. But as with all value judgments, even if there is objectivity in the match—e.g., rhythmic and mood affinity between dance and music—the accompanying value judgment is fundamentally questionable. Nothing says that only positive affinity is necessary to make a “great” match. One could argue that happy lyrics go with dark music as a spooky combination—think porcelain doll in the dark—or as a spoof. On the other hand, dark lyrics over dark music can be of great comedic value depending on the listener’s mindset. What is taken seriously by some is derided by others. The song Black Sabbath may be taken seriously by “true heavy metal” fans and Satan-fearing parents, while others laugh off the cheesy horror lyrics. The fundamental separation between the evil theme and metal as “evil music” is such that people could invent the genre of “white metal,” i.e., Christ-hailing metal, and you can be sure that this genre has its legion of fans who swear by it alone. In any case, celebrating evil or god in songs is and has always been as deridable as your next self-proclaimed black metal misanthropes signing to a label and negotiating tour support.

The act of viewing a medium as a composite medium for the purposes of value judgments, “medium pairing,” is not to be mistaken with the interpretation of a heteromedium-specific narrative. Narratives are about change, which statements on fitness for purpose (“the costumes fit the theme so well!”) are not. So when one talks of “medium-specific narrative,” one considers changes across the medium pairing, not the pairing itself. Typically, the medium-specific narrative of a song (to mind: not album, not artist, but the individual song itself) focuses on melody, not style, genre, technique, or production (all invariants with respect to the narrative), and only deals with harmony insofar it partakes in producing melody. The purely musical narrative is in most cases tangent to the lyrics, although one can always try to look for narratives from the coupling of music with lyrics (rather than the meaning of music in lyrics, or the meaning of music in emotion), just as comics combine drawings with text into a new type of narrative material, as was seen with Touti and his Exhaust Pipe.