Book/From the Interpretation of the Average Value to Pure Reconstruction

From the interpretation of the average value to pure reconstruction

It appears like the interpretation of the medium-specific narrative is in direct opposition to the interpretation of the average value, or that the narrative opposes the mosaic. But at the core, the difference is a shift in terms of interpreted content.

The mosaic of interpretation is conceptually kept separate from the interpreted content. However, it builds on the ambiguity between interpretation and content. Far from being just an evaluation of content, the mosaic forms a seamless tissue with the content and has a direct influence over our appreciation of it. A consumer review can help you better appreciate a product you already have, the same way an art connoisseur can make you re-evaluate what you thought was a worthless piece of junk.

Because of this, and because we regularly consume interpretations as a way of enjoying content—for example, it is well-known that people read reviews of things they already have just for the pleasure of it—it makes sense to subject them to value judgments as well. I will henceforth produce arguments that may motivate the shift to a style of interpretation that calls for a minimalist interpretation of content and the pure transcription of medium-specific narratives. I call that transcription pure reconstruction.

The conventional medium delimitation. How styles of interpretations only differ by how one decides what the content is. On the hedonistic rather than value-based or utilitarian motive of such a decision.

The ambiguity between interpretation and content

“Is the interpretation right?”

This is a question that I imagine is very frequently asked in art classes.

Skepticism regarding authorial intent and the concept of author itself is well-documented, starting with Wimsatt and Beardsley’s The Intentional Fallacy and Roland Barthes’ The Death of the Author. I will henceforth point out how such concepts relate to the mosaic.

Art teachers tell us that one should look at a painting for at least a full 15 minutes in order to let everything sink in properly. But let’s hear what they have to say of Van Gogh’s The Starry Night:

The center part shows the village of Saint-Rémy under a swirling sky, in a view from the asylum towards north. The Alpilles far to the right fit to this view, but there is little rapport of the actual scene with the intermediary hills which seem to be derived from a different part of the surroundings, south of the asylum. The cypress tree to the left was added into the composition. Of note is the fact van Gogh had already, during his time in Arles, repositioned Ursa Major from the north to the south in his painting Starry Night Over the Rhone.

❞Now my retort to the teacher’s advice:

- How could anyone possibly come up with the above commentary by just staring at the painting, whether for just 15 minutes or 15 hours ?

- Leaving out the biographical details that can only come to one’s knowledge “from the side,” how couldn’t anyone come up with the rest of the commentary in less than 15 seconds? The intra-medium discourse of the quote can be summed up as: “The painting depicts the view outside at night. The center part shows the village under a swirling sky. There is a cypress tree to the left of the composition.” Anyone with eyes can see that.

Answering both questions brings out the fact that the interpretation is anything but the painting “sinking in.” There is certainly an autonomy of the interpretation. I mean autonomy in the sense that one cannot guess stuff such as “the painting depicts the view outside his sanitorium room window at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.” Not that that fact is arbitrary or irrational. Actually, most descriptions that would qualify as “natural” and “normal” show a similar autonomy. Naming a figure by its name is such a description. When descriptions of Velázquez’ painting Las Meninas identify the central figure as Infanta Margarita, they imply that she is, beyond her pictorial representation, the “five-year-old princess who later married the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, and was at this point Philip IV and Mariana of Austria’s only surviving child,” which in turn coerces the meaning of the other figures around her. Identifying Velázquez as both the painter and a figure of the painting is another innocent-looking identification with far-reaching consequences for the resulting interpretation, as demonstrated by the first chapter of Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences.

Yet, despite being “natural” and “normal,” how descriptions enter in a relationship to the painting is quite opaque—most of the time, you just have to believe what you’re being told. The mosaic is the structure that can join pieces of information inside and outside the painting. I will henceforth make the argument that the mosaic can be seen as encompassing anything recognized as either interpretation or content.

Interpretation+content as a composite medium in its own right. The conventions and ethics of medium delimitation: interpretation as a convention as to what is content and what is not. How this question can prompt the cultural shift in interpretation patterns by subjecting them to value judgments. The case of the reviews we read for pleasure

Interpretations getting out of hand is a well-known cliché of modern art. Should the flower of artspeak fully blossom, one can’t help but admire the unsolicited prolixity, often surpassing the admiration for the work itself. One starts to become cynical: isn’t artspeak the real art? Here is a review of an Yves Klein painting that entirely and uniformly blue:

What do you feel before a blue monochrome?

An IKB monochrome is appealing, mesmerizing, appeasing. You want to sink in it. It is light. It is almost a silky carpet. You want to touch it, to lie on it, to project your dreams on it. It is like a world of peace, some kind of paradise. If you compare two blue monochromes, you can see that they are different. For Yves Klein, blue is the color of infinite space. But he doesn’t want you to only see through the “eyes of the body.” For him, the quality of a painting is difficult to put into words. In his painting, he has left a bit of his soul, of his sensibility, of his energy! According to him, if you pay close attention, you can sense this force, this “something.” It is never the same for each painting, because even if it is about coating a surface with the same color, he applies the color differently, with more or less energy. That is why each painting is different!

❞The critic must have researched their stuff ten times harder than Yves Klein. The quasi-totality of the commentary arguably lies outside the painting medium. They talk about the critic’s associations, the painter’s thoughts, and how the painting compares to other blue monochromes. The effect on the viewing experience is twofold: either you get something out of the interpretation that enriches the experience, or you don’t. If you do, the effect is that of compounding the medium with the reviewer’s statements. In effect, you say: I enjoy the work together with these associations, the painter’s thoughts, in relation to other blue monochromes, as if the work of art was not the painting alone, but the combination of the painting and the interpretation.

A less obvious case of compounding is the interpretation of text: in order to understand any text, the reader must know and assume many things in addition to reading—linguistic, cultural, scientific, conventional, and so on. But even then, interpretation has its own medium, with its own rules, that distinguishes it from the text medium. I already mentioned the fact that the axes of interpretation that make up a mosaic are ordered regardless of content. The order, and even which exact axes were used, are more a matter of convenience and habit than a matter of content. When a movie is tackled from the aspects of plot, characters, style, and so on, those aspects are almost never meant to be understood in any particular order, and no aspect is individually necessary for the interpretation to function. Contrast this degree of freedom to the actual movie, whose aspects must be gradually revealed in a scripted order. In fact, a compulsive artifact of interpretation is the chronological reordering of this scripted order if it is non-linear——e.g., the efforts by fans to piece together the timeline of the TV series Lost. But this endeavor is a rewriting, and a writing in its own right.

But the mosaic structure is not specific to interpretation. It is also an important property of stories as we traditionally understand them. If you look atomically at a story’s transition points, whether the story is fiction or non-fiction, you see that they form a narrative that, however tight-knit and smooth-looking, is actually as loose as a mosaic. Take the story of Jesus revealing himself as the Son of God (fiction or not is not the point): nothing in Jesus’ actions establishes a necessary filiation with God until the story says so, not even his miracles. The miracles only prove that he is super powerful. Superman can smash buildings to pieces and shoot laser beams from his eyes, yet nobody mistakes him for a son of God. God could have endowed Jesus, a mere human, with a few super powers. Although he can walk on water, it may be the case that he gets sun burns just like everyone else. He may possess resurrection power and yet be inept at maths. And why “Son of God?” Why not God Himself? Any answer—including God not having a physical shape—is going to be unsatisfying insofar it will only displace the question to the explanation—a fundamental deficiency of causal explanation. Due to that deficiency, disbelief is uncondemnable on logical grounds: how can one condemn someone for not believing a story that is only plausible, let alone a witness account? And don’t be mistaken. This is not even a critique of the implausibility of Jesus’ story. On the contrary, a real critique could point out that it is too plausible, too calculated, from Jesus’ humble debut to the apotheosis of the Ascension. In fact, interest would pick up if Jesus didn’t manage to resurrect. Following his numerous demonstrations—healings, walking on water, etc.—wouldn’t a failure to resurrect be an even greater miracle than the Resurrection?

The looseness, and the illusion of fate and of a “faithful account of reality,” is something very quantifiable, and can be a budget decision in the business of making stories, in the sense that loose stories cost less to produce than tight stories. One can see this in relation to story-driven video games such as The Walking Dead: The Game, which, like the TV show, was released in episode sets called “seasons.” In that game, the player drives the story by making choices, such as which character they want to save at the expense of another character. Yet, despite the praise, players have come to recognize (and resign themselves to) the locality of their choices. If you decide to save a given character, the saved character is going to be killed off anyway, at one point or another, and the story will be the same after that, whichever character you chose. This was most evident at the end of the second season, where players could trigger any of 6 very different endings. But the beginning of season 3 soon demonstrated that the choice of ending didn’t matter: as far as the main storyline is concerned, any choice was going to be inconsequential. The player’s choice is written off using flashbacks to flesh out in a short sequence how the player’s choices integrate into the main storyline. This is understandable from a budget perspective: if the choices weren’t loosely connected to the main storyline, the developers would have had to create almost 6 different games.

If a story is a loose causality chain, its interpretation is a loose description thereof (chronological reordering being just one example of a loose description), with both joining into a super-mosaic. Take this interpretation of Albert Camus’ The Outsider (the passage in quotes is quoted from the novel):

« Meursault is a character without emotions or moral conscience. He lives by his senses. The death of his mother is a mere casual event that happens to him: “Maman died today. Or yesterday maybe, I don’t know. I got a telegram from the home: Mother deceased. Funeral tomorrow. Faithfully yours. That doesn’t mean anything. Maybe it was yesterday.” »

The interpretation forms a context to Camus’ text that shifts the focus to what kind of person the narrator is, rather than on the specificity of his reaction to his mother’s death. Now, consider this modified version of The Outsider:

« Things happen. I perceive them as they happen. I don’t see why I should care. For example, Maman died today. Or yesterday maybe, I don’t know. I got a telegram from the home: Mother deceased. Funeral tomorrow. Faithfully yours. That doesn’t mean anything. Maybe it was yesterday. »

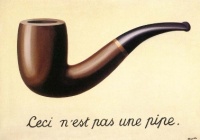

My additions form a context to what follows, just like “Maman died today” forms a context to “Or yesterday maybe.” These changes are not as out-of-place as they may seem: they move the focus to the place where the interpretation took its focus. When Magritte writes “it’s not a pipe” over the picture of a pipe, he realized what I just did: the possibility to feed the interpretation into the work itself. Interpreting the modified quote is the same as interpreting the interpretation in the original quote.

Interpreting interpretation is exactly what we did with the interpretation of the average value. Rather than reading it the usual way, i.e., as a means to forge one’s opinion (should I adhere to the reviewer’s conclusion and follow his recommendations?), I figured out the mosaic-like medium-specific narrative underlying it. This is the same as interpreting the medium-specific narrative of any text. In conceptual art, the work is a recipe to produce a work of art, rather than a finished product. It already looks like the interpretation of a finished product. By interpreting the recipe, we basically hint at the fundamental possibility of interpreting an interpretation the same way we interpret art.

Obviously, an interpretation is not held to the same standards as a work of art. It wouldn’t make sense to criticize an interpretation for not being creative. It would be like arguing that one cannot criticize a singer if one can’t sing (which many do, by the way). Yet, when talking about the separation between interpretation and content, it usually is with the expectation that the interpretation enriches the content. In this regard, the fusion of the content with the interpretation could be praised for being genius, or criticized for being boring. In fact, some authors use that perspective in non-artistic fields. For example, Deleuze and Guattari criticized œdipian psychoanalysis for its inability to cope with the schizophrenic—whether the clinical schizophrenic or “schizophrenic art”:

The question is not anymore whether the interpretation or the theory is true or not, but whether it is worth it in the most subjective sense. Deleuze and Guattari’s answer to œdipian psychoanalysis, schizo-analysis, actually attempts to bridge schizophrenia and “true art.” But far from providing a factual basis for the myth of natural value and “true art,” their departure from œdipian psychoanalysis rather cements the theory as content that can be subjected to value judgments. Deleuze and Guattari link Œdipus to a form of social repression (the bad thing) that struggles to embrace the reality-embracing revolutionary nature (the good thing) of the schizophrenic. But isn’t schizo-analysis at risk of ending up like œdipian psychoanalysis? Can’t Nature become “artificial territorialities,” and can’t Œdipian psychoanalysis become a “stroll,” a “breath of fresh air,” if only because its territorialities, while forcing the clinical material into a rigid, arguably close-minded schema, must skillfully juggle with the speculative elements of analysis in what constitutes the psychiatric equivalent of artspeak?

Both œdipian psychology and artspeak add value to the content, whether or not one agrees on the “authenticity” of the attempt. Modern art critics often come under fire for instrumentalizing content as a way to flaunt their culture. They may, however, have a point: without their vast culture and precious sensibilities, an artwork such as a monochrome painting would probably amount to nothing. Although it may seem obvious to the cynic that artspeak is contrived to sell the artwork high, why would the amateur not want to enjoy the work more—short of buying it—if provided the means to do so, however “artificial?” In fact, is “artificiality” an “authentic” concept? People are already hard-pressed to define what authentic is: what work isn’t in some way derived from other works? What good does it do to compound the intractable “authenticity” of content with the “authenticity” of interpretation?

The dichotomy between interpretation as content and art in general is a conventional barrier that collapses under the critical gaze. For example, the cut-up technique in literature is considered disruptive, and therefore an innovative method of art. But an interpretation that endeavours to see everything chronologically is as disruptive to cut-up narratives as the cut-up technique is disruptive to chronology. Whether one side of the coin should be seen as more disruptive than the other is a matter of bias. People typically believe that disruptive art is fundamentally different and better in an objective, intemporal way. But disruption can only exist for a limited period that doesn’t quite live up to the intemporal status typically demanded of “great art.” After Tony Iommi disrupted hard rock with heavy metal riffs, the techniques and aesthetics quickly became a trend that is anything but disruptive. The outsider will give extreme metal the credit of embodying a kind of fundamental freedom, but insiders know better. Even the most “extreme” and “progressive” metal bands can be as calculated in the construction of its image as a manufactured pop star, following predictable patterns of music history—whether merging influences, going retro, or improving on musicianship. Conversely, the most basic interpretation is fundamentally as disruptive as Jorge Luis Borges’ Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote. When Borges makes Pierre Menard the author of Don Quixote, it’s an act that we all do when assigning an author to a text. In both cases, it’s the same type of mosaic. Here, Borges takes Cervantes’ story as far as Pierre Menard can, in the same way the author’s biography printed on the flap of a book jacket prolongs the book content and seems to synergize with it. The only difference is that Borges officialized the process as Art, the same way Marcel Duchamp could officialize a toilet as Art, or Yves Klein an empty room with white walls as an art exhibition.

Now, the modern art critic’s flatulence, as either a means to enjoyment or just plain Art, wouldn’t attract nearly as much criticism if the reviews were clear about their object. If it were clearly stated that the quoted review of Yves Klein’s Blue Monochrome was of “Yves Klein’s Blue Monochrome viewed through the lens of the sensibility and knowledge of Sandrine Andrews,” then it wouldn’t look as factitious, self-indulgent, and unaccountable. It would acquit itself as a subjective experience catering to whatever purpose—e.g., the purpose of submitting a plausible enjoyable experience. To this effect, reviewers could use very explicit warnings, or a convention of preliminary medium delimitation, that would clearly state upfront what content the interpretation applies to and what material it draws from. The recourse to convention here is not a concession to the argument that “interpretation is as much art as content” is weak, for every work of Art is already a convention that determines what we should consider as content.

With the convention that interpretation itself is art, the critique of critique, or the interpretation of interpretation, has relinquished all rights to treat interpretation differently from content. The interpretation becomes immune to the critique of flatulence, in the sense that it doesn’t purport to have any kind of informative or utilitarian quality. It is not merely there to prove a point about the content, as implied when one accuses a critic of pulling off rhetorical tricks. It is there as something to enjoy (or not) as-is. From a hedonist’s standpoint, interpretation works the same whether the interpretation injects “unauthentic” ideas into the work or not. What the recipient of the interpretation is concerned with is no longer the process of telling the content and the interpretation apart, but how, given both the interpretation and the work, and without questioning the legitimacy of their association, they can interpret them as a unit and make them personally relevant.

So interpretation can be, and often is, judged differently. Conceptually, interpretation is conceived as “outside” the content, which means that “great” interpretations have their own kind of genius: the genius of discovering things hidden from us, that no amount of close analysis would have helped us unlock. Critics are privy to the act of enveloping works in some mystic aura that coerces their audience into respect, e.g., the aura of the “classics.” Critics “reveal” that they are classics, as if their value judgments was backed by some savant secret. But if interpretation is a form of content, then implying that there is some secret at work becomes just another literary device, just like saying “based on actual events” as the preamble to a book or movie. This statement is now subject to the same judgment criteria as traditional content, especially the judgment criterion of tedious repetitiveness. As a co-artist, the critic exposes themselves to an entirely different type of criticism which quickly learns to tire of the judgment values because they always look the same and suffer from the same recurring issues. They are judged for things other than the truth and accuracy of their statements. Under these conditions, the job of the critic may evolve to become a fully fledged artistic endeavor, or, at the other extreme, embrace purely referential interpretation, i.e., a style of interpretation that tries to stay as close to the content as possible.

The evolution of the critic’s job, as prompted by the critique of interpretation itself, is akin to a magician having to please an audience of blasés. For the latter, the wow effect of magic performance has died out: seeing stuff disappear and reappear induces boredom after a while, no matter how clean the effects look. Therefore, the magician decides to make a show out of revealing tricks, à la Penn and Teller. It is an interesting concept based of the fact that 2 tricks with the same effect are not equal depending on their implementation. A teleportation trick is not as impressive if you know the magician uses a twin. Similarly, a card magician like Lennart Green, who finds any card named by the audience from a normal deck in seconds, wouldn’t be as impressive if he uses a stooge in the audience or electronic ink on the cards. To prove that they “don’t cheat while cheating,” the magician needs to reveal the trick, which is painful for them, but is also a form of entertainment (puzzle game) that can actually renew the appreciation for how the trick is performed (for example, the reveal shows that the trick takes a lot of technical skill to pull off). Even non-magician people are willing to pay for this kind of thing.

Interpretation as content isn’t any more special than traditional content. Coincidentally, making the ordinary special and the special ordinary in art is an operation that is only limited by imagination, taste and habit. Habit is what informs us that Fantine in Les Misérables is not as special as if she had superhero powers. But it’s just habit. In literature, people flying around or shooting beams from their eyes is nothing special. The retort could be: it is special in the context of a historical novel like Les Misérables. But the genre of the historical novel, as a part of interpretation, is also a part of the content because we so choose. In other words, our conventions integrate the concept of historical novel so well into Les Misérables that it blends with it, to the point where an a posteriori notion—we only know that Les Misérables is a historical novel in part because it has no trace of superhero, not the other way around—is passed off as an a priori notion that says: there was no way that Les Misérables could have featured a superhero. Victor Hugo would never have allowed it. Here too, the author and his speculated intentions are as much a fact of interpretation as he is a part of the content seen as an a priori historical novel.

If interpretation is seen as content by convention, then an interesting shift in perception occurs. The pertinence of the facts of interpretation is not taken for granted anymore. They acquire contingent and arbitrary qualities. Actually, this shift of perception doesn’t even need a convention in some cases. For example, while product reviews primarily purport to be read as buying recommendations, it is well-known that many are read purely for pleasure, including by product owners, whether it’s to read other opinions, enjoy the writing, or relive something in a nostalgic sense.

Here are examples of perception shift occurring from considering interpretation as content:

- The demystification of the perfect interpretation. With the mosaic of interpretation, there was always the promise of justness and completeness—i.e., the promise of a perfect interpretation. If the mosaic has always been conventional content, perfection was a conventional perfection all along, i.e., a perfection limited to a specific way of viewing content. No matter what, the erudition, sophistication, and fitness for purpose displayed by interpretation originate from an arbitrary decision or convention.

- Interpretation as content doesn’t get dismissed anymore if it is not true or smells of pompousity, pedantism or any sort of hidden agenda. One may, however, criticize it as cliché or just plain bad art.

- Truth and being informative don’t automatically hold value anymore, and can be subjected to value judgments. For example, the concept of author can be seen as an overused cliché. Making lists of pros and cons can be seen as a messy organization of information. Value judgments can be seen as self-indulgent and tactless in the sense of being thrown out there with no regard to their actual relevance to the readers.

Now the critic faces a choice. The interpretation of the average value is no longer the only option. It no longer suffices to be as informative as possible. And it no longer suffices to be inspired by the content and wax poetic over it. If the critic wants to make art, they can take this intention to the limits of its consequences, without having to incur the mockery of a cynical readership. Or they can choose another style of interpretation.

Preliminary medium delimitation: the politics of making the critic aware of choices in content and interpretation

Sometimes the only obstacle that stands between the critic and alternative forms of interpretation is that they weren’t even aware they had a choice.

Preliminary medium delimitation is the formal process of stating upfront what is content and what the critic brings to the table. It makes the critic get rid of a fundamental guilt—i.e., not a conscious guilt, but one that quietly accompanies the partiality to non-universal values. Preliminary medium delimitation is the acknowledgment of a conscious choice on the critic’s part. If the critic chose an interpretation of the average value, then they have indeed formally taken responsibility for any value judgment. In effect, they say, “I know these value judgments are subjective—sorry for inconveniencing anyone.” While this may sound overly apologetic or falsely modest, it is also the case that reviewers often find themselves accused of being too subjective or not prefacing their opinions with adequate gravity.

Preliminary medium delimitation not only allows the critic to be square with their audience, it also encourages self-critique. The intent is to, before they even write a single word, let them know the types of criticism they’re exposing themselves to if they choose this or that style of interpretation, including a new type of criticism that targets the structure of the mosaic itself, as we’re going to see.

The hedonistic choice of interpretation style

When consuming art, a style of interpretation constantly but unconsciously coerces our perception of the content and, by extension, our enjoying (or not) art. If art is all about maxing out enjoyment, then it makes sense to knowingly choose the style of interpretation. Likewise, since interpretations/reviews are often consumed for pleasure, it makes sense for critics and reviewers to consider various styles. In the internet age, gaining access to a wide variety of works is not an issue anymore. This is not the case with interpretation, where a unique-thought mindset has cemented a lack of choice. But with the interpretation of the average value being exposed as a very specific style (rather than all-purpose and universal), this could change.

A shift in interpretation paradigm may be in order if interpretation:

- fails to account for the unique content;

- feels overused or abused.

What follows is a study of the interpretation of the average value as a sameness with a characteristic quality of contingency.

How the interpretation of the average value is a stereotype

The mosaic as the structure of being tacked-on

The content communicated by the mosaic feels same-y despite the infinite recombinability of the mosaic. The infinite recombinability is a double-edged, and means that one can spend a lifetime doing the same thing (recombining mosaic parts) without noticing it. Sameness is not reason enough to dislike something. In fact, the things we like tend to be the same. This is a cornerstone of consumerism, and the reason why one can say, “I like this kind of music,” or “I like reading this writer,” and so on. But after a while, the sameness can become overbearing and overpower our appreciation of content, not because the content allows it, but because our interpretation formats it as a mosaic.

Sometimes the content itself is a mosaic. When that’s the case, it can illustrate simultaneously both the flexibility and contingency of the mosaic structure. When the content follows a non-artistic agenda, that contingency translates into what could be described as gratuitousness or worse. Take for example the America’s Got Talent 2021 audition of magician Dustin Tavella. In his performance, Tavella asks different judges to pick randomly a date, a time of day, a name, and a word. In the final reveal, he asks the show host to open an email received hours prior to the show. The email contains a picture of one of his adopted sons in a cardboard box on which we can read the chosen date and name (“On February 21, 2020, Judge Smith made Dustin and Kari my mommy and daddy”). In the background, a wall clock shows the chosen time of day. Another picture shows the biological mother holding up a sign with the chosen word on it. Where is the mosaic here? The themes of the pictures are obviously orthogonal to the magic trick: the picture could have been of something else. In other words, the pictures are a piece of mosaic, just like the random choices gratuitously assembled into a phrase. The pictures could be anything else and the magic trick would be just as strong technically. The mosaic nature of the performance is such that the collages don’t even have to make sense: besides the fact that no Judge Smith ever granted Dustin and Kari custody on February 21, 2020, but why would you even write this on a cardboard box? What the interchangeability of the pictures conveys to us is the feeling that the themes are tacked on. If you want to be cynical, you could say the mosaic structure of the trick gave Tavella leeway to insert his personal story in order to win sympathy points (which worked pretty well, considering he unabashedly reused the same adoptive hero dad story on his way to winning the show, going so far as to have his wife wheel in the kids just to show some text on their T-shirts). At a more fundamental level, it can be argued that this tacked-on-ness is deeply ingrained into the mosaic structure as a content format.

The stereotype of conjectures. Reality and truth as artistic devices.

A mosaic of ideas is limitless. The ideas therein are free to embrace contradiction. This carefreeness not only means that the most non-sensical mosaic of ideas can be contrived, but that the most no-nonsense mosaic of ideas is somewhat contrived at a fundamental level. Let’s be careful here: the quality of being contrived is not proportional to the artificiality of the ideas. In fact, artificiality is not always in inverse proportion to realism, as real life often looks more fictitious than fiction. How about spiders using air bubbles to breathe underwater? Birds resting on one leg, or insects sleeping horizontally, grasping at stalks with the sheer force of their mandibles, legs folded under them or extended out? Surely, this must be a hoax. Is it?

Saunders (Hymenoptera Aculeata of the British Islands, p. 308) says of Chelostoma, a bee: “The male usually spends its nights curled up in flowers, but Smith says that at other times he has observed them hanging to blades of grass by their mandibles” suspending themselves in a horizontal position with their hind legs stretched out in a line with their bodies.” Some of these were killed by chloroform and remained attached after death.

In the Proc. Cambridge Entom. Club, Oct. 9, 1874 (Psyche, II, pp. 40, 41), it is recorded that Mr. Scudder showed a specimen of “Ammophila glyphus which rests at night by seizing a blade of grass with its jaws and holding itself extended either with or without the use of its middle and hind feet.” Many specimens were seen at different times acting in this manner. The specimen is figured in Morse's First Book of Zoology, p. 94, Fig. 91.

[…]

There are doubtless other records, but sufficient evidence has been given to show that various bees and fossorial Hymenoptera have curious sleeping habits. The exposed position and the use of the mandibles are very remarkable. That a bee or wasp can support its body horizontally all night by the jaws alone seems almost beyond belief.

❞As Hume notes, the only things that hold reality together are causal relationships:

23. If we would satisfy ourselves, therefore, concerning the nature of that evidence, which assures us of matters of fact, we must enquire how we arrive at the knowledge of cause and effect.

I shall venture to affirm, as a general proposition, which admits of no exception, that the knowledge of this relation is not, in any instance, attained by reasonings a priori; but arises entirely from experience, when we find that any particular objects are constantly conjoined with each other. Let an object be presented to a man of ever so strong natural reason and abilities; if that object be entirely new to him, he will not be able, by the most accurate examination of its sensible qualities, to discover any of its causes or effects. Adam, though his rational faculties be supposed, at the very first, entirely perfect, could not have inferred from the fluidity and transparency of water that it would suffocate him, or from the light and warmth of fire that it would consume him. No object ever discovers, by the qualities which appear to the senses, either the causes which produced it, or the effects which will arise from it; nor can our reason, unassisted by experience, ever draw any inference concerning real existence and matter of fact.

❞Facts, whether true or not, have a fundamentally conjectural quality due to their reliance on empirical evidence to form a consistent reality, which is really nothing more than an open-ended belief structure. One such conjectural fact is the existence of a creator or author, whether man or god. Hume discusses the fundamental separation between the Creator and His alleged work:

In general, it may, I think, be established as a maxim, that where any cause is known only by its particular effects, it must be impossible to infer any new effects from that cause; since the qualities, which are requisite to produce these new effects along with the former, must either be different, or superior, or of more extensive operation, than those which simply produced the effect, whence alone the cause is supposed to be known to us. We can never, therefore, have any reason to suppose the existence of these qualities. To say, that the new effects proceed only from a continuation of the same energy, which is already known from the first effects, will not remove the difficulty. For even granting this to be the case (which can seldom be supposed), the very continuation and exertion of a like energy (for it is impossible it can be absolutely the same), I say, this exertion of a like energy, in a different period of space and time, is a very arbitrary supposition, and what there cannot possibly be any traces of in the effects, from which all our knowledge of the cause is originally derived. Let the inferred cause be exactly proportioned (as it should be) to the known effect; and it is impossible that it can possess any qualities, from which new or different effects can be inferred.

The great source of our mistake in this subject, and of the unbounded licence of conjecture, which we indulge, is, that we tacitly consider ourselves, as in the place of the Supreme Being, and conclude, that he will, on every occasion, observe the same conduct, which we ourselves, in his situation, would have embraced as reasonable and eligible. But, besides that the ordinary course of nature may convince us, that almost everything is regulated by principles and maxims very different from ours; besides this, I say, it must evidently appear contrary to all rules of analogy to reason, from the intentions and projects of men, to those of a Being so different, and so much superior. In human nature, there is a certain experienced coherence of designs and inclinations; so that when, from any fact, we have discovered one intention of any man, it may often be reasonable, from experience, to infer another, and draw a long chain of conclusions concerning his past or future conduct. But this method of reasoning can never have place with regard to a Being, so remote and incomprehensible, who bears much less analogy to any other being in the universe than the sun to a waxen taper, and who discovers himself only by some faint traces or outlines, beyond which we have no authority to ascribe to him any attribute or perfection. What we imagine to be a superior perfection, may really be a defect. Or were it ever so much a perfection, the ascribing of it to the Supreme Being, where it appears not to have been really exerted, to the full, in his works, savours more of flattery and panegyric, than of just reasoning and sound philosophy. All the philosophy, therefore, in the world, and all the religion, which is nothing but a species of philosophy, will never be able to carry us beyond the usual course of experience, or give us measures of conduct and behaviour different from those which are furnished by reflections on common life. No new fact can ever be inferred from the religious hypothesis; no event foreseen or foretold; no reward or punishment expected or dreaded, beyond what is already known by practice and observation.

❞Hume says of the author “that you have no ground to ascribe to him any qualities, but what you see he has actually exerted and displayed in his productions.” The fundamental separation between content and author runs so deep that plausibility isn’t only about the biographical facts, but also about the pieces of evidence and the proof of these facts. Who is the author of the natural theory of selection? For most, Darwin comes to mind. But Alfred Russel Wallace is also a name associated with the theory. The differences in their lives, personalities, and beliefs, are vaporous constraints in regard to the fluidity with which someone can be established as the author of something. Wallace was a radical thinker, so his being credited as the originator of the theory comes across as logical:

But, alas, causality is one tricky beast. Darwin, on the other hand, was never a radical thinker to begin with.

Perfect plausibility is certainly not an absolute criterion for ascertaining biographical facts: I could say that the essence of creation lies precisely in surpassing one’s condition as a creative source. Otherwise one would have to believe all fiction written in first person to be autobiographical. On the other hand, we shouldn’t need an autobiography to be titled Extraterrestrials Took Me To Their Planet to see the fundamentally conjectural quality present in all biographies. Every biographical detail is extraterrestrial-ish, so to speak, by virtue of being in a conjectural relationship with all the other parts of a mosaic.

Now, the alleged reason we take a biography as authoritative is not only because it has been proven, but also because the proof itself is authoritative, and the proof of the proof, and so on. But let’s not kid ourselves: we actually don’t need this deep a proof. As much as we pride ourselves not to be fooled, the fact is that we do take a lot of information at face value and that this doesn’t prevent us from believing in the least. Reliability is more a wishful state of mind than even a half-hearted attempt at consolidating belief. And by extension, so is truth, in a psychological sense. The impact of truth isn’t related to whether truth is true, but to the degree by which one can believe it, which is why one can improve one’s sex life by pretending the sexual partner to be someone else.

Also, we never need scientific proof, only an appearance of scientificity. In most cases, a handful of people may have had first-hand knowledge, while thousands of others repeated what they heard or read. The mantra is known: “the sources have a good reputation, there are rules in the profession, everybody reports the same thing, people are honest, lots of people checked the facts for me.” Since everybody thinks the same and unloads the burden of proof onto others, almost nobody knows for real. We could call the problem of only knowing from hearsay—including the hearsay regarding the sources—the Wikipedia reliability problem.

What we have on Wikipedia is a self-reinforcing reliability. If you have wrong information but link it to a “reliable source with a good reputation” on Wikipedia, then the error was made “reliable” by proxy. Of course, Wikipedia itself remains “reliable” because it has reliability policies, and through reverse psychology, makes the error more reliable without anything actually happening. How many actually click on the footnotes to check the sources? Probably not many, and for a good reason. We don’t need to. We can “feel” truth. Truth is first a manipulative feeling in Art and informative media alike. That’s why movies “based on a true story” are so popular: reality is a source of good thrills. Sure, it is disappointing when a lie is revealed, but even then, you still had a great time while it lasted—and who knows, the lie might unexpectedly turn out to be true.

One can always say: nothing is random and everything happens for a reason. But it’s always in a “yet to discover” mode, as it is the nature of causality to be open-ended. Truth is fragile for this very reason. Whatever else you may have proved, you can’t prove that no new fact will ever emerge to contradict your proof, since reality as knowledge is but a giant mosaic that can be added to in a million ways.

Yet, reality, or rather the belief in it, is glorified for a good reason: it elevates the experience, even when the belief is wrong or shaky. Most passions harbor the sense of belonging to a consistent reality, a consistent identity, and a consistent history. But these passions always follow from an amnesic grasp of reality that is just a step away from a rude awakening. An example would be the sports club fan. The sports club is the consistent reality lived from the inside, with a consistent history. But finding the consistency that would justify the unflagging loyalty of fandom is a struggle. Think of a situation that is increasingly common: a club bought by a foreign investor, probably from the Middle-East or China, now able to afford the greatest stars in the business (think the Paris Saint-Germain soccer club). Almost overnight, most of the staff and players no longer speak the national language. The club’s primary objective is no longer the national championship. It has its sights set on the international stage, because that’s where money and fame are. Except maybe for the club’s name and the players’ uniforms, everything has changed. Even the fans have changed. A new breed has emerged: supporters jumping bandwagons as soon as they smell the promise of victory parades. In this situation, it is hard to explain the unconditional loyalty of the dying breed: the long-standing fans who proudly fought through the humble years of tight budgets and local talents traded to the highest bidder. Love is blind. And now, in the times of newfound luxuries, it is more blind than ever. The wins are nice, but what exactly does the continued support to the club mean? As a club that is expected to run away with the national championship every year in what basically amounts to a lose-lose situation (if it doesn’t win, then it ought to be ashamed, and if it does, no big deal since it was just expected)? As a political entity whose faces are mercenaries who barely knew the club just a few months ago? What is exactly the consistency of the reality of the club as an entity with a history?

Another kind of identity would be one’s race, country, or nation. It is so strong that people go to war and die for their sake. It is all good, but sometimes, you need to go deeper into the implications of going to war for something as abstract as a country. As Mark Twain pointed out, “the country is what you unconditionally serve, the government is what you serve if it deserves it.” And more often than not, it turns out that what you end up doing when “going to war for your country” is the noble thing to do is actually risking your life for a very flawed government—think the invasion of Iraq by the U.S.—or driven by less-than-noble agendas—think neo-colonialism sold as war against terror.

Now, the consistency of a reality may be hard to prove, but it doesn’t mean it can’t be done. If I choose to, given the means, I can go out just now, probe the world and prove that my belief is firmly anchored in reality. If I’m already out there probing the world, I can always probe some more. The whole counter-argument is contained in the “if.” Concretely, if I am a long-time fan of the club that became the latest shiny new toy of a billionaire, I can go out and prove that my loyalty still makes sense. But when all the people that I cherished there are all gone, sacrificed to the “winning at all costs” (literally) mentality, when the club has relocated to new state-of-the-art facilities, what I will find is maybe a brand and some paperwork. Does it still justify my loyalty to “the” club? Wasn’t “the” club that I truly support exactly the one back in the old days, but not beyond?

Even “real reality” has its whimsical ways. Whoever diligently follows the news with an appetite for reality is in for quite a ride. One day the Sandy Islands exist. The next day, they are imaginary. One day, you believe that black widow spiders owe their name to female spiders eating their mate. The next day, you read:

In the ongoing saga of the John F. Kennedy assassination theories, the “Dictabelt recording” spawned the equivalent of a table tennis match between different realities.

Scientific investigations were conducted by “acoustics analysts” and conclusive numbers were provided to support the second gunman theory:

However, there was a discrepancy when it came to locating the microphone at the time of the recording:

An “expert on photographic evidence” confirmed the discrepancy:

Finally, both the FBI and the National Academy of Sciences conclusively rebutted the HSCA:

On May 14, 1982, the panel of experts chaired by Harvard University's Norman Ramsey, released the results of their study. The NAS panel unanimously concluded that: “The acoustic analyses do not demonstrate that there was a grassy knoll shot, and in particular there is no acoustic basis for the claim of 95% probability of such a shot. The acoustic impulses attributed to gunshots were recorded about one minute after the President had been shot and the motorcade had been instructed to go to the hospital. Therefore, reliable acoustic data do not support a conclusion that there was a second gunman.”

❞But Dr. Donald B. Thomas, who agreed with the HSCA conclusions and published his findings in an issue of Science & Justice, had the last word:

Or maybe not.

Reversals of beliefs and the way we deal with them expose our ideas of reality and truth as a mosaic of facts which may be true, but which we freely combine with each other, even with wrong facts.

I don’t question the nature and utility of belief, nor do I lament facts not being facts enough. Let’s just ask: in the context of art, what do realism and truthiness bring to the experience that is not stereotypical? The answer probably lies in the difference between the live TV coverage of a school shooting and the mockumentary of a school shooting. In both, any universe of facts has the shape of a mosaic of conjectures. The concept of plot itself is a mosaic: something happens, so X does something, which causes Y, etc. Fictional events flow plausibly from each other, they can freely mingle with historical events, and this perfectly works with time-travel too! In fiction, facts can have the exact same realistic outlook as “real” facts, even if they involve time-travel (at least if you don’t think too hard about it).

Deconstructing reality is a sure way to attract accusations of reality denial and nihilism. But it is based on analyzing what is being said, which is an act full of reality. The act of reading words in a fictional work is always more real as an act than the reality suggested by words in the newspapers. The act of looking at a painting is always more real than any meaning ascribed to it. The statement “Portrait of Gertrude Stein is the portrait of Gertrude Stein” is a conjecture indeed. Picasso himself, assuming the portrait is his work, may have said so. But only the belief in the printed records may back up the conjecture today, and even then, who is to say Picasso didn’t lie or only partially told the truth? Decades of people repeating what they read or heard don’t change the conjectural nature. Tomorrow, an article or the latest x-rays may change things up. Denying the possibility of that happening would be the true reality denial, as such things happen all the time.

Reality being somewhat lacking is not even a problem in practice, as people find satisfaction in it easily enough. Too easily maybe? The point is that knowledge is not as satisfying as it could be. Satisfaction in knowledge, especially causal knowledge, happens to the degree the answer to the “why?” question doesn’t call for another why. However, no answer can be ultimate, if only because the fact that we stop at it is a convention. You may be satisfied if I explain to you that the sky is blue because it absorbs longer wavelength colors. You may, however, also rightly ask why it absorbs longer wavelength colors (because my answer may really just amount to a definition of the color blue in wavelength terms), and when I explain this to you, you may ask another explanation and so on, until we decide to conclude that “it is so because it is so.” There's also the God answer. But when your local Jehovah’s Witnesses claim that “Man needs to know why he exists,” their answer is not satisfactory for the very reason that there cannot be any satisfactory answer. To “Man is such because God wanted it so”, one is always entitled to reply “Why did God want it so?”, etc. Stopping at God is relatively satisfying but absolutely arbitrary, because there is no logical ground to stopping the questioning. Similarly, nothing can logically prevent there being a Creator of God, and then a Creator of the Creator of God, and so on. And if someone argues that God is a transcendental Being so that logic can’t apply, then any kind of metaphysical rhetorics is fair game, so why not a transcendental Creator of the transcendental God?

This gratuitous extensiveness of causality contrasts with the comprehensiveness of the medium-specific narrative. This contrast could be compared to Derrida putting the “unformed mass of roots, soil, and sediments of all sorts” against the “irreducible point of originality” contained in his careful reading of Rousseau:

In general, the “unformed mass” of reality proves to be too complex to support the kind of simplistic consistency that produces popular trends in analysis, including the trend of having an author, which one could supposedly rationally infer from the text. As soon as one carefully examines the open-ended nature of the inference, the concept begins to break down:

Even the concepts of truth and understanding are simplistic insofar as they relate to simplistic concepts. To the literary analyst, understanding literature is, besides other things, about knowing its author.

Whether a concept is fundamentally conjectural or too simplistic to have a consistent meaning, it can still function. But it is as unsatisfying as the belief in it is cheap to manufacture. The lack of boundaries of the concept of reality should be the promise of an infinite source of knowledge, but in practice, we kind of know what to expect: an “unformed mass of roots, soil, and sediments of all sorts,” a “tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture.” In art, it is a cliché, either as an artistic means of expression, or as a consumer’s demand for realism, e.g., when we’re asking for believability in acting even though it’s, well, acting.

The inconsequential conjecture stress-test

Common wisdom tells us to judge the merits of a statement in relation to its implications. If someone says that alcohol accounts for 40% of all traffic accidents, a common conclusion would be: wow, alcohol is truly bad. But if 40% is an awful lot, then I have bad news for you. 60% of all accidents are caused by sober drivers. So, if we must do something about alcoholism because of the 40%, then what do the 60% say about driving sober? What this relativization tells us is that you can’t use this statistic as-is for the purpose of condemning alcoholism. You need better statistics for that.

Here the question is about the merits of the mosaic of the interpretation of the average value. The main properties of the mosaic follow from its conjectural nature:

- Extensibility

- Interchangeability of the parts

Applying common wisdom here, we can try to relativize their contributions to the merits of the interpretation through “stress-testing.” After all, if something is so good, what harm could it do to have more and more of it?

- Stress-testing extensibility by adding more and more relevant conjectures, trying to assess the critical mass above which any further addition would feel redundant. The limit is psychological. The unbounded combination of interchangeable facts increasingly overwhelms, causing a numbing effect. More is not always better. Above a critical mass, each additional fact becomes more and more insignificant. A mosaic is like a mental counter. The greater the magnitude, the lesser the clarity and the greater the numbing effect. Two deaths are intuitively clear, 98738749293478 deaths less so, in the sense that it is, in effect, indistinguishable from 983987984339 or 9808799787987 deaths. Above a certain level of magnitude or precision, numbers become a monotonous litany of digits that elicits indifference toward the precise digits. That’s why, to the genocidal dictators, a million more victims added to many millions isn’t a particularly involving decision, and conversely, it is difficult to “proportionately” blame them for each and every death: it is impossible to feel for the suffering individual when the death toll is in the millions. And to those who would like to hold them accountable for each and every death, it doesn’t matter to them: whether they get 3000000 or 10000000 years is immaterial. Whatever is free and overabundant loses any sense of differentiation, whether reward or penalty. This is the issue with conjectures: they are as abundant and interchangeable as our sense of plausibility is open to overuse and abuse.

- Stress-testing interchangeability by replacing conjectures with other conjectures. Interchangeability is basically the fact that our tolerance for facts is wide enough to accomodate many versions of reality, especially in art where it is, in a way, the artist’s job to create an ambiguity regarding the “real” author by transcending their real-life conditions. The merits of any fact should then be judged against its possible substitutions. It is indisputable that the favored criterion for a choice here would be truth, although, in practice, it really is plausibility, or rather, acceptability. So how would interpretations of a painting turn out if alternative facts were used? To make things interesting, artspeak will be used to exaggerate the means by which plausible facts can be manufactured.

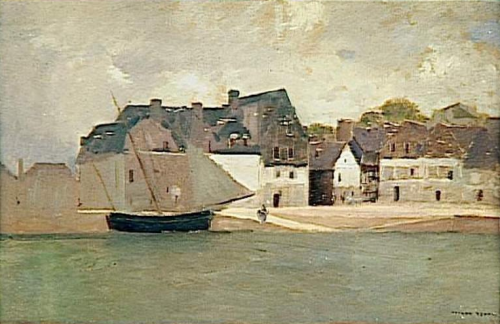

How do you appreciate this painting by Odilon Redon…

…if you tell yourself it is Edvard Munch’s?

« This placid scenery is a… far cry from the painter’s most iconic painting. Yet, somehow, the broody atmosphere and contained escapist symbolism announces the heavier tones of his future work. »

Pollock’s at a very young age?

« Young Pollock was still in the process of figuring out his own style. Here he captures perfectly the “calm before the storm” in a relatively academic but self-affirming style not unlike early Picasso. »

Pollock’s a few days before his death? That changes everything.

« Pollock was intent on returning to his artistic roots. The horizontal composition serves an open-endedness of structure surfing the undercurrent of evolution. »

Bill Clinton’s?

« The elegant simplicity of the environment conveys the values of middle-class America. It is served by the portuary symbolism of the American Dream that was central to president Clinton’s domestic policies. »

Martin Luther King’s?

« The boat of peace has long sailed. Martin Luther King took what is a predominantly white man’s art into a pacific expression of open society. »

A description of a painting through its author needs to be not only interesting but also logical. If it were only interesting, one could probably choose another, more interesting author to build the interpretation on. If it were only logical, what would be the point of mentioning the author, except maybe a sense of overbearing duty and tradition?

By playing on the concepts of extensibility and interchangeability, we get to relativize what was inevitably put into motion in the “truthful” interpretation, namely the fundamental conjecturing.

One wouldn’t want to conjecture more than necessary. The value judgment here is that, as an artistry, conjecturing is a mind game one can expand at will, and as such, a self-indulgent method of writing. The average value is the necessary product of trying to make sense of all the self-multiplying conjectures. It is akin to aggregating highly differentiated individuals into statistics, by virtue of losing all sense of the individual.

Yet, conjecturing is able to produce medium-specific narratives rather than mosaics. Obviously, some combinations of conjectures are better than others. Sometimes the whole is more than the sum of the parts. That’s why it might make sense, as part of conventional medium delimitation, to view conjectures as content, because (1) they are such an essential component of the experience, and (2) it demands quite some thought to come up with an interesting mix of conjectures.

Pretend you don’t know this painting:

And then consider the interpretation:

An opposite interpretation would be interesting and logical as well:

Both interpretations are clearly conjectural, since they second-guess an intent behind the painting. Both hold enough significance that they could warrant an inclusion in the work, as Magritte did:

Whether, as a conventional medium delimitation, one considers the totality of the painting and the interpretation, or the totality of the painting with the interpretation inside the canvas, it is the same to the hedonist or whoever is willing to maximize the experience.

So the issue is not necessarily interpretation being too artificial—“outside the canvas,” pretending to be a correct account of reality—or not artificial enough —“inside the canvas,” pretending to be art. Rather, it is the stereotyped totality of the interpretation together with the work, as either a habit, a trend, or an overused cliché. For example, the characterization of a work through the biography of its author is expected of any reasonable interpretation. Yet, in the words of Richard Strauss writing to Stefan Zweig at the time of Nazi Germany: “Do you believe I am ever, in any of my actions, guided by the thought that I am 'German'? Do you suppose Mozart was consciously 'Aryan' when he composed? I recognise only two types of people: those who have talent and those who have none.” I could also quote:

Or:

While this seems like a lot for a bunch of guys with tattoos, they are intelligent, as manifested by the “simple” complexity of structures, where they have distilled what it is they mean to communicate into ideas, so well-defined variations, Slayer-style, offer no detours but complement the overall theme.

❞The mind games based on skill and impressiveness: trivially deprecated opinions, and the correspondingly trivial form of progress

The mind games of skill and impressiveness are close to the mind games of authorship. They also rely on a reality, here in the form of a value scale that is as arbitrary as it is transient. Thanks to them, people get impressed by what “most can’t do.”

The actual performance has to involve belief in a particular feat requiring skill and hard work. This belief is often exposed as an ignorance of its conditions. Take a young drummer performing for a talent show. A member of the jury, an authoritative figure in the music business, declares he is really impressed. On Twitter, people are already condescending because they see this as the reasonable performance of a well-schooled second-year drummer. This isn’t a rare occurrence. People often get wowed by virtuoso acts that millions of no-names in orchestras could perform backward in their sleep. Many more are impressed by fake performances in general—lip-syncing, doping, etc. Some believe that they rarely, if ever, get faked out because they have a keen sense of the authentic. It’s always the same old argument: you can’t know you got fooled, because it’s the essence of the fool not to know. It’s like people claiming that experience shows that crime never goes unnoticed, so you better not go against the law. But the argument falls apart all the same: the moralist can only know of the crimes that got publicity. The millions they don’t know about have flown under the radar.

Still, the point is not about being right or wrong, but that, as hard as one tries not to be fooled, the sensation of being impressed is the same whether fooled or not. At some point in their life, the most respected authority learned the existence of playback singing, doping in sports, or tool-assisted speed runs in video gaming, which threw off their whole perception of a particular performance. If authenticity looks absolute and beyond any doubt, one can just wait it out. In the movie Goodfellas, a gangster’s wife shows off the family’s impressive TV set to her guests:

The vanity makes us smile. But do we always need to take such a look back to be able to relativize our present values and the self-indulgence underlying them? Curved smartphones have taken the place of the convex cathodic tubes, but we are, psychologically and philosophically, in the same position today as the gangster’s wife. History repeats itself. What was in the past is not impressive anymore and the present becomes the new impressive absolute. In most cases, the absoluteness is only a big sign screaming “absolute,” like the digital display next to a track and field athlete making the V sign because they broke a world record and “made history.” One can see from the hurried look to the screens as the track runners cross the finish line that the sensation of “beating the world record” is not something that is derived from the actual performance as it occurs, but from a very explicit suggestion taken very seriously after the performance. The runner sure ran fast, but to really overcome the past and make history, one needs a sign that screams “fast fast fast” after the fact. The relationship between impressiveness and the actual performance is so volatile that one may ask: why shouldn’t one be unimpressed, even after a look at the screens? Why would jumping to the conclusion that they made history be more “authentic” than a reaction such as “the wind was probably blowing hard in their back,” or “the guy was probably on performance-enhancing drugs?” It is not that counter-intuitive or unnatural. In fact, a cynical attitude has already taken over in professional cycling, where all great performances are instantly stained by suspicions of doping. In all cases, it is never a question of actual perception. Not the perceived speed, for nobody is impressed by an ordinary horse running twice as fast than the best sprinter in the world. The question of relativity, especially in relation to one’s own capabilities, has little legitimacy. Why should I be impressed by Usain Bolt if he only runs twice as fast as I do? Why shouldn’t I set the bar higher? Nothing but my expectations. Despite the relative form of “X times faster,” the whole proposition “X times faster is impressive” is actually an absolute statement. Even when expressed as “impressive for the times,” it still makes an absolute claim, as a generalization of the claims of a group of people. The 80% approval ratio that translates into a “universal acclaim” in Wikipedia’s critical reception sections is an instance of this form of absolute claim.

The passage of time is useful in exposing false absolute claims that something is impressive, but mere careful reading of such claims can also do the same. Take the DNA of the ape 99% similar to the human DNA. This genetic similarity impressed even scientists. What the stat doesn’t tell, and what most people don’t care to check, is the relativity of the numbers. An ant could be 90% similar. Mice are actually 97.5% similar. The fallacy of the 99% absolute is the fallacy of believing that 99% is impressive in itself.

Sometimes, your mere background will inform you of the imposture. For example, a black metal fan raves to a prog rock fan about the “groundbreaking” use of keyboards or female vocals by his favorite band, something the prog rock fan isn’t impressed with in the least. On the other hand, something as characteristic such as black metal’s ambient noise over monotonous drumming might impress them more.

Another way to debunk absolute claims is by sensing what will become of them. If the hour record in cycling is 51.115 km, then you just know that some time in the future, “impressive” will rather apply to 52 km. Beliefs beg to be negated, if only because they carry in them the potential of their own denial. They also entail a certain form of progress conditioned by the beliefs. When that’s the case, a surprising development is akin to being surprised when it was only you deceiving yourself in the first place. Victor Hugo’s Hernani owes its fame to a few authorities making up rules about how a play should be written:

- The unity of action: a play should have one main action that it follows, with no or few subplots.

- The unity of place: a play should cover a single physical space and should not attempt to compress geography, nor should the stage represent more than one place.

- The unity of time: the action in a play should take place over no more than 24 hours.

Such rules happen to look so arbitrary today that we clearly see that it was only a matter of time before someone broke them (even unintentionally). The same can be said of everything that is “impressive,” in every area of knowledge. The Copernican Revolution is only revolutionary because people got too much ahead of themselves in geocentrism. Bohr’s Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics is shocking or highly controversial only to people who swore to the mechanistic interpretation of all phenomena. The habit of having to speak up in a definitive tone about the truth value of everything effectively makes Wittgenstein’s “whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent” an advance in human wisdom. And this suggestion equally applies to both Einstein, when he says in relation to Bohr’s interpretation that God does not roll dice, and Bohr, when he allegedly suggested to Einstein not to speculate about what God ought to do.

Therefore, there is no necessity to the feeling of being impressed. This absence of necessity expresses a contingency of feeling that mirrors the structural contingency in the mosaic. For example, being impressed by singing acts in talent shows is just one step away from laughing, considering how they’re trying to impress (and how the trained audience reacts) is so predictable and cliché. Basically imitate Mariah Carey or Whitney Houston.

The “too much, not enough” syndrom

Compared to a medium-specific narrative, the interpretation of the average value suffers from “too much, not enough.” Conceptual art can help expose the discrepancy.

The “set of written instructions” generates the work, leaving out the “traditional aesthetic and material concerns.” Now, the relationship between the build instructions and the generated work is two-ways: if one views the generated work in light of the build instructions, then it appears that those instructions actually reflect some medium-specific narrative in the generated work.

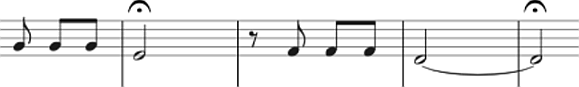

Consider Goya’s The Third of May 1808. The build instructions corresponding to one medium-specific narrative of this painting could read as follows:

1. Draw groups of figures on a horizontal plane.

2. Draw the groups tight, inside convex shapes, so as to create a mutual exclusion between a left side and a right side.

3. Draw in the center a standing figure arms up: one arm is tangent to the groups on the left side, the other arm to the groups on the right side.

4. Paint a shirt of the same color on the center figure, covering the arms and the torso

The items of this list relate to each other in a medium-specific pattern that is relatively unique. Most of them can be found in the first paragraph of this Wikipedia quote:

On the right side stands the firing squad, engulfed in shadow and painted as a monolithic unit. Seen nearly from behind, their bayonets and their shako headgear form a relentless and immutable column. Most of the faces of the figures cannot be seen, but the face of the man to the right of the main victim, peeping fearfully towards the soldiers, acts as a repoussoir at the back of the central group. Without distracting from the intensity of the foreground drama, a townscape with a steeple looms in the nocturnal distance, probably including the barracks used by the French. In the background between the hillside and the shakos is a crowd with torches: perhaps onlookers, perhaps more soldiers or victims.

The Second and Third of May 1808 are thought to have been intended as parts of a larger series. Written commentary and circumstantial evidence suggest that Goya painted four large canvases memorializing the rebellion of May 1808. In his memoirs of the Royal Academy in 1867, José Caveda wrote of four paintings by Goya of the second of May, and Cristóbal Ferriz—an artist and a collector of Goya—mentioned two other paintings on the theme: a revolt at the royal palace and a defense of artillery barracks. Contemporary prints stand as precedents for such a series. The disappearance of two paintings may indicate official displeasure with the depiction of popular insurrection.

❞Besides the fact that the description throws so many details at the reader that it obscures any overall message it might have, it misses from the build instructions the narrative that strings together the convex groups, their opposition, and the synthetic function of the central figure. The quote reads more like an enumeration of elements of a visual mosaic. On top of the visual mosaic is the juxtaposition of various non-visual statements, including:

- value judgments: “by a stroke of genius”

- speculations: “his arms flung wide in either appeal or defiance,” “probably including the barracks used by the French,” “perhaps onlookers, perhaps more soldiers or victims”

- context of the painting, including the author’s intention and other historical considerations

Many of these elements of the mosaic look extra to the medium-specific narrative of the build instructions, and what it is missing in terms of narrative is expressed in the overall impression of an inorganic whole. Following is a general assessment of the interpretation of the average value:

(a) It is “not enough” in the sense that its microscopic analysis pictures the whole as a mosaic of isolated features—in painting, that could be the analysis of the brush strokes, the study of the colours, the contours, the objects, etc.—which it can only correlate to each other by virtue of them being lumped together. This is not so much a critique of close reading and “lemon-squeezing analysis” as a recognition of its intrinsic limitations. For example, when Schopenhauer puts music under the microscope, the smallest details—“the effect of the minor and major”, “the change of half a tone”, “the entrance of a minor third instead of a major”—and the most banal observations you’ll ever find—“quick melodies,” “elaborate movements, long passages”—appear wonderful to him:

Just listening to him, you’d think that any music is a “work of genius.” It seems beyond belief that someone would suggest such an absurdity—of course, believing in the existence of banality and mediocrity is subjective, but so is the qualification of “genius.” It may be that mediocre music was a post-eighteenth century invention. Or it may be that Schopenhauer had so much tunnel vision that he couldn’t see the implications of his generalizations.

(b) It is “too much” in the sense of the inconsequential conjecture test, when the work is analyzed in contexts that exceed—and ultimately eclipse—its content. For example, myopic analysis typically classifies a song by genre (black metal), sub-genre (death black metal), ideology (national socialist black metal), country (Norwegian black metal), ethnicity (Viking black metal), etc. All these classifications are equally valid, and the choice of one over another is quite tangential to the content. A classification has value only insofar as it lumps different works together and loses their individuality. If the complexity of the interpretation of a single work was the cause of unintelligible mosaics, now imagine for a whole genre the inconsistencies and debates that classification generates. Personally, I still try to wrap my head around the expression “classical music” when it throws in the same bag the “pure classicism” of Brahms and the “nationalist symphonic poems” of Bedřich Smetana. The same with more refined categorizations: the aforementioned composers have also been categorized as “mid-era Romanticism.” If anything valuable can ever emerge from classifications—besides the mercantile concerns of matching buyers and sellers based on superficial criteria—it’s left unspecified and can be considered as the magical upside of interpretation.

Pure reconstruction

I call reconstruction an interpretation that tries to limit itself to transcribing a medium-specific narrative from content agreed upon through a convention of medium delimitation. The principle of only transcribing is what I call pure referentiality. A reconstruction is always purely referential. This principle can be understood in relation to the issue of “quoting out of context.” For example, we can reconstruct a discourse of François Hollande and write: “François Hollande says that he doesn’t like rich people.” Actually, Nicolas Sarkozy quoted him during the 2007 presidential debate against Segolène Royal, to which the latter replied, “You shouldn’t take things out of context.” Sarkozy did have a political agenda, which was to show that Hollande wasn’t the rallying force he purported to be. In the context of a reconstruction, the quote is to be understood in context by virtue of pure referentiality. The quote doesn’t reflect Hollande’s aptitude for the presidency as much as it refers to a particular point in his entire discourse. The difference between Sarkozy’s quote and the reconstruction’s quote is that in the former case, it may well be that, as Royal pointed out, the fault was on Sarkozy for taking things out of context, while in the latter case, the fault for taking the quote out of context would be the reader’s, for not accounting for the pure referentiality.

Pure reconstruction is a reconstruction whose convention of medium delimitation tries to stay within bounds of what could be accepted as “intra-medium content.” To use the same example, this means that a pure reconstruction of the Hollande discourse wouldn’t try to make a point, such as Hollande being a leftist or trying to be a demagogue. It only transcribes what he said, not what he intended to say or what he looked like to the electorate.

Pure referentiality

Incorruptibility as a convention