Difference between revisions of "Book/The Medium-Specific Narrative"

Thaumasnot (talk | contribs) |

Thaumasnot (talk | contribs) |

||

| (42 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Book Part}} | |||

==Interpretation of the medium-specific narrative== | |||

The alternative to the interpretation of the average value is what, in the absence of a more marketable expression, I call the “interpretation of the medium-specific narrative.” The medium-specific narratives are the opposite of the mosaics. Instead of a loose whole, one searches for some tightly-knit structure, with all extras removed. A work contains many medium-specific narratives that may overlap. There may not even be a “the one” medium-specific narrative that the creator is supposed to have designed and intended for their audience. The existence of “the one” is best left to speculative (and ultimately sterile) endeavours. Some narrative may look like it, but in general, the medium-specific narratives are modest in scope and fundamentally hedonistic: the satisfaction of finding one is purely subjective. | |||

The expression “interpretation of '''the''' medium-specific narrative” (non-plural) as used in this essay is somewhat misleading. It actually means an interpretation that reveals one of the medium-specific narratives of the interpreted content. You can think of “'''the''' medium-specific narrative” as the content itself, and the “interpretation” as a medium-specific sub-narrative that results from a filtering of “'''the''' medium-specifc narrative”. | |||

===The medium-specific narrative as a narrative of elements related to each other due to the nature of the medium. The interpretation of the average value as a juxtaposition of disparate elements. Proximity of the medium-specific narrative to the content as a timeline of events that actually happen to the consumer. The interpretation of the medium-specific narrative is essentially a rendering of a medium-specific narrative, with an implicit non-committal value judgment that doesn’t detract from objectivity.=== | |||

Narrative interpretation is an endeavor to view a work as, broadly speaking, a “story,” i.e., every element in the work is viewed in light of previous elements, the '''premises''' or '''context'''. If the elements form a succession of events in the same timeline, characters, locations, etc., then we recognize the traditional concept of story. But if the elements are the regions of a painting or the motifs of a musical piece, the concepts of “story” and “premise” take on a peculiar quality '''relative to the nature of the medium'''. In a pop song, an element could be a section, for example the chorus, and its premise could be the verse. Depending on the merits of doing so, one could look at a more granular level where an element could mean a phrase, the segment of a phrase, or even a note. Such an element can be seen as the premise to any other element that follows it in the song. In a painting, an “element” could, for example, mean a painted region, an object, or a motif. The concept of “premise” here can be somewhat misleading, as there isn’t a declared timeline. In this case, I like to generalize the definition of “premise” to mean “another element of the painting” which both gives it context and is given a context by it, depending on which element you view as the premise. The elements of a painting implicitly bond together through an implicit timeline, which is the timeline of the viewing experience. The movement of the viewer’s gaze from one region of the painting to another creates a subjective timeline of perceptions, a “story” of perceptions. This timeline tends to be ignored because the observer tends to compress it during the cognitive process—e.g., when we see a portrait, we recognize the face almost instantaneously, without going over the facial features individually. We’ll later see how this “photographic memory” can prejudice visual media. | |||

The physical frame of the narrative (the canvas, the pages, or the sound track) is a convention. It narrows the search for narratives. But you could imagine looking for (and finding) medium-specific narratives in Nature or in any unintended arrangement of objects. This has important ramifications for how one looks at conventional art. The focus is now on the perceptions '''as they happen to the observer, not as they are intended by some intelligent being'''. In fact, the medium-specific narratives don’t refer to an external intelligent being at all, since it is outside the medium. On the other hand, a mosaic is the result when one talks of such an intelligent being, a Creator or Artist, in relation to the work. | |||

The “medium specificity” of the narrative means that the elements of the narrative are homogeneous parts of the same medium. In other words, the narrative stays '''intra-medium'''. It is an interpretation of a content as a self-contained unit, filtering perceptions happening on a closed timeline (not the timeline of a story in the traditional sense). As a medium-specific narrative, a song is a succession of perceptions (melodies, harmonies, notes, and so on) and nothing else. By contrast, the interpretation of the average value results in a mosaic of features, including mood, theme, genre, and so on. Therefore, the listener first experiences the elements of medium-specific narratives. Considerations like theme or genre are high-level interpretations of these elements. | |||

===The | ===The mosaic as the medium-specific narrative of reviews=== | ||

The interpretation of the average value reveals itself when one begins to | The interpretation of the average value reveals itself when one begins to analyze reviews, and more particularly their narrative structure (or rather the lack thereof), rather than just their supposed usefulness. In a way, reviews are works about works, using a stylistically distinctive thought process that builds upon content through an amnesic process. As such, the reviews have their own medium-specific narratives, of which the mosaic is the invariant. We saw an example through the interpretation of a modern art review. | ||

===A medium-specific narrative from John Keats’ ''Ode on a Grecian Urn''=== | More generally, medium-specific narratives are not confined to art. In terms of methodology, their interpretation doesn’t make any distinction between art and science, between fiction and non-fiction, between review and reviewed content. In fact, most critiques and analyses you will find in this text are interpretations of the medium-specific narratives of various papers, books, discourses, reviews, and everyday chatter. The interpretations are presented rather informally for the ease of reading, while staying recognizable by the characteristic minuteness with which they capture medium-specific intricacies. | ||

===A medium-specific narrative from John Keats’ ''Ode on a Grecian Urn''. Interpretation writing styles=== | |||

I chose John Keats’ ''Ode on a Grecian Urn'' because it is short and well-established in academic circles. | I chose John Keats’ ''Ode on a Grecian Urn'' because it is short and well-established in academic circles. | ||

| Line 78: | Line 80: | ||

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”||John Keats|''Ode on a Grecian Urn''}}</div> | Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”||John Keats|''Ode on a Grecian Urn''}}</div> | ||

When I look for a medium-specific narrative, I try to find one that roughly covers the whole work | When I look for a medium-specific narrative, I try to find one that roughly covers the whole work, one that justifies the work as a unit. Here’s one: | ||

# The narrator questions a silent “thou.” | # The narrator questions a silent “thou.” | ||

# The narrator associates the silent (“those unheard are sweeter”) with the eternal (“canst not leave […] nor ever,” “never, never”, “For ever,” etc.). | # The narrator associates the silent (“those unheard are sweeter”) with the eternal (“canst not leave […] nor ever,” “never, never”, “For ever,” etc.). | ||

# The eternal is then associated with | # The eternal is then associated with repetitions of “happy” framed between assonant words (“Ah, '''happy, happy''' boughs!”, “More happy love! more '''happy, happy''' love!”). | ||

# Finally, when the eternally silent (“Thou, '''silent''' form, dost tease us out of thought as doth '''eternity'''”) says something, it addresses the narrator’s questioning (“all '''ye need to know'''”) through structures of | # Finally, when the eternally silent (“Thou, '''silent''' form, dost tease us out of thought as doth '''eternity'''”) says something, it addresses the narrator’s questioning (“all '''ye need to know'''”) through structures of repetiton, reminiscent of the framed repetitions of “happy”: “'''Beauty is truth, truth beauty''', that is '''all ye know''' on earth, and '''all ye need to know'''.” | ||

All the terms of the interpretations are reused and combined in different contexts. In (1), the “silent thou” is asked questions which are addressed in (4). The | All the terms of the interpretations are reused and combined in different contexts. In (1), the “silent thou” is asked questions which are addressed in (4). The repetitions of the answer “beauty is truth, truth beauty” echo the repetitions of the words happy and love in (3), but in a non-silent context which contrasts the silence in (1) and (2). A narrative thus emerges. | ||

This narrative is medium-specific in the sense that it takes elements directly from the poem with almost no recourse to subjective interpretation. I say almost, because there is certainly some interpretation there. I | This narrative is medium-specific in the sense that it takes elements directly from the poem with almost no recourse to subjective interpretation. I say almost, because there is certainly some layer of interpretation there. I did skip many details, even entire parts of the poem. I also didn’t mention the stanza structure or the rhyme schemes. Implicit in these oversights is an assessment that they weren’t needed in the narrative I wanted to highlight. If you study the stanza structure or the poem’s themes, as most scholars do, you get invariants rather than a narrative. But this choice, to prefer this poem-wide narrative over invariants, is already an act of subjective interpretation, even if, in the last analysis, I just highlighted certain passages of the poem and their relationships. | ||

I could cook the interpretation a little bit, as it is a little too raw as it is. I could add some commentary that would express the feelings and value judgments that led me to this narrative. I could say this: | |||

{{c|John Keats thus makes us realize that our | {{c|John Keats thus makes us realize that our questionings are superfluous, in the sense that the answer was already implied in the narrator’s enthusiastic exuberance. The answer is in the rythmic expressivity—whether in the questioning itself (the series of “what”) or in the insistence on eternity, happiness and love—that seems to anticipate T.S. Eliot’s criticism of the “grammatically meaningless” statement that “beauty is truth, truth beauty.”}} | ||

I will usually choose to stay away from this style of | I will usually choose to stay away from this style of '''writing''', but this is a purely personal choice. I personally like to address an audience that doesn’t need to be spoon-fed and will arrive at its own conclusions. In fact, I would argue that the raw interpretation doesn’t need any conclusion. The elements of the narrative are interlinked with one another in such a way that the whole point is lost as soon as one tries to wrap things up in a generic conclusion—i.e., the narrative is self-contained and self-conclusive, somewhat like “beauty is truth, truth beauty” is self-contained and self-conclusive. In fact, any type of value-based conclusion would attract the sort of (rightful) criticism against awkward attempts at penetrating non-objective concepts through objective interpretation—cf. Derrida’s criticism of Jean Rousset who tried to describe passion in literature (or at least invite his readers to sense it) using only geometrical concepts like “rings,” “symmetry,” “helices,” and so on: | ||

{{quote|At the start of the essay ''Polyeucte or The Ring and the Helix'', the author cautiously warns us that, if he insists upon “schemas that might seem excessively geometrical, it’s because Corneille, more than any other, practiced symmetries.” Moreover “this geometry is not cultivated for itself,” “it is in the great plays a means subordinated to passionate ends.” | |||

But what does this essay actually tell us? Only the geometry of a theater which is, however, “that of the mad passion, of the heroic enthusiasm.” Not only does the geometrical structure of ''Polyeucte'' mobilize all the resources and attention of the author, but the whole teleology of Corneille’s trajectory is attached to it. | |||

|Au début de l’essai intitulé ''Polyeucte ou la bouche et la vrille'', l’auteur prévient prudemment que, s’il insiste sur “des schèmes qui peuvent paraître excessivement géométriques, c’est que Corneille, plus que tout autre, a a pratiqué les symétrie”. De plus “cette géométrie n’est pas cultivée pour elle-même”, “elle est dans les grandes pièces un moyen subordonné à des fins passionnelles”. | |||

Mais que nous livre en fait cet essai? La seule géométrie d’un théâtre qui est pourtant “celui de la passion folle, de l’enthousiasme héroïque”. Non seulement la structure géométrique de ''Polyeucte'' mobilise toutes les ressources et toute l’attention de l’auteur, mais à elle est ordonnée toute une téléologie de l’itinéraire cornélien. | |||

|Jacques Derrida | |||

|Force and Signification, in ''Writing and Difference'' | |||

}} | |||

===Rediscovering intra-medium movement=== | ===Rediscovering intra-medium movement=== | ||

====Rediscovering intra-visuality. Restoring the primacy of the viewing angle==== | ====Rediscovering intra-visuality. Restoring the primacy of the viewing angle.==== | ||

Keeping the interpretation intra-medium is counter-intuitive to | Keeping the interpretation intra-medium is counter-intuitive to most of us. “This painting represents the king”: this is a very natural statement to read, though it is hardly concerned with the objective content. If the reader of the statement sticks to what the interpretation '''actually communicates''', and tries to visualize a painting entirely through it, they would imagine a king sitting on a throne, a crown, maybe a heraldic symbol. The visuals, along with all the non-visual facts (including the fact that the king is represented), contribute a “story” that goes beyond the mere visuals. | ||

{{quote|The ''Equestrian Portrait of Charles I'' (also known as ''Charles I on Horseback'') is an oil painting on canvas by Anthony van Dyck, showing Charles I on horseback. Charles I had become King of Great Britain and Ireland in 1625 on the death of his father James I, and Van Dyck became the Charles’ Principal Painter in Ordinary in 1632. This portrait is thought to have been painted in about 1637–38, only a few years before the English Civil War broke out in 1642. It is one of many portraits of Charles by Van Dyck, including several equestrian portraits. | {{quote|The ''Equestrian Portrait of Charles I'' (also known as ''Charles I on Horseback'') is an oil painting on canvas by Anthony van Dyck, showing Charles I on horseback. Charles I had become King of Great Britain and Ireland in 1625 on the death of his father James I, and Van Dyck became the Charles’ Principal Painter in Ordinary in 1632. This portrait is thought to have been painted in about 1637–38, only a few years before the English Civil War broke out in 1642. It is one of many portraits of Charles by Van Dyck, including several equestrian portraits.||English Wikipedia | ||

| | |||

|English Wikipedia | |||

|''Equestrian Portrait of Charles I'' | |''Equestrian Portrait of Charles I'' | ||

}} | }} | ||

Such stories are independent of | Such stories are independent of the visuals but it is assumed that these stories “merge” with the visuals and serve their meaning and, ultimately, value. They build a viewerless world: | ||

{{quote|But when we say that the for-itself is-in-the-world, that consciousness is consciousness of the world, we must be careful to remember that the world exists confronting consciousness as an indefinite multiplicity of reciprocal relations which consciousness surveys without perspective and contemplates without a point of view. ''For me'' this glass is to the left of the decanter and a little behind it; ''for Pierre'', it is to the right and a little in front. It is not even conceivable that a consciousness could survey the world in such a way that the glass should be simultaneously given to it at | {{quote|But when we say that the for-itself is-in-the-world, that consciousness is consciousness of the world, '''we must be careful to remember that the world exists confronting consciousness as an indefinite multiplicity of reciprocal relations which consciousness surveys without perspective and contemplates without a point of view'''. ''For me'' this glass is to the left of the decanter and a little behind it; ''for Pierre'', it is to the right and a little in front. It is not even conceivable that a consciousness could survey the world in such a way that the glass should be simultaneously given to it at the right and at the left of the decanter, in front of it and behind it. This is by no means the consequence of a strict application of the principle of identity but because this fusion of right and left, of before and behind, would result in the total disappearance of “thises” at the heart of a primitive indistinction. Similarly if the table leg hides the designs in the rug from my sight, this is not the result of some finitude and some imperfection in my visual organs, but it is because a rug which would not be hidden by the table, a rug which would not be either under it or above it or to one side of it, would not have any relation of any kind with the table and would no longer belong to the “world” in which there is the table. The in-itself which is made manifest in the form of the ''this'' would return to its indifferent self-identity. Even space as a purely external relation would disappear. '''The constitution of space as a multiplicity of reciprocal relations can be effected only from the abstract point of view of science; it can not be lived, it can not even be represented'''. The triangle which I trace on the blackboard so as to help me in abstract reasoning is necessarily to the right of the circle tangent to one of its sides, necessarily to the extent that it is on the blackboard. And my effort is to surpass the concrete characteristics of the figure traced in chalk by not including its relation to me in my calculations any more than the thickness of the lines or the imperfection of the drawing.||Jean-Paul Sartre | ||

the right and at the left of the decanter, in front of it and behind it. This is by no means the consequence of a strict application of the principle of identity but because this fusion of right and left, of before and behind, would result in the total disappearance of “thises” at the heart of a primitive indistinction. Similarly if the table leg hides the designs in the rug from my sight, this is not the result of some finitude and some imperfection in my visual organs, but it is because a rug which would not be hidden by the table, a rug which would not be either under it or above it or to one side of it, would not have any relation of any kind with the table and would no longer belong to the “world” in which there is the table. The in-itself which is made manifest in the form of the ''this'' would return to its indifferent self-identity. Even space as a purely external relation would disappear. The constitution of space as a multiplicity of reciprocal relations can be effected only from the abstract point of view of science; it can not be lived, it can not even be represented. The triangle which I trace on the blackboard so as to help me in abstract reasoning is necessarily to the right of the circle tangent to one of its sides, necessarily | |||

to the extent that it is on the blackboard. And my effort is to surpass the concrete characteristics of the figure traced in chalk by not including its relation to me in my calculations any more than the thickness of the lines or the imperfection of the drawing. | |||

| | |||

|Jean-Paul Sartre | |||

|''Being and Nothingness'', The Body as Being-For-Itself: Facticity, 2 | |''Being and Nothingness'', The Body as Being-For-Itself: Facticity, 2 | ||

}} | }} | ||

In the | In the viewerless world '''signified''' by the painting, the king is not just a bi-dimensional figure on a surface. The work could very well be a sculpture without invalidating a single word of the interpretation, down to the smallest detail: | ||

{{quote|Charles is depicted wearing the same suit of armour, riding a heavily muscled dun horse with peculiarly small head. To the right, a page proffers a helmet. Charles appears as a heroic philosopher king, contemplatively surveying his domain, carrying a baton of command, with a long sword to his side, and wearing the medallion of the Sovereign of the Order of the Garter. His melancholy, distant expression was seen as a sign of wisdom. He wears the same suit of tilt armour in both equestrian paintings […] | {{quote|Charles is depicted wearing the same suit of armour, riding a heavily muscled dun horse with peculiarly small head. To the right, a page proffers a helmet. Charles appears as a heroic philosopher king, contemplatively surveying his domain, carrying a baton of command, with a long sword to his side, and wearing the medallion of the Sovereign of the Order of the Garter. His melancholy, distant expression was seen as a sign of wisdom. He wears the same suit of tilt armour in both equestrian paintings […] | ||

| Line 127: | Line 131: | ||

}} | }} | ||

The interpretation quoted above captures a viewable object in a particular viewing angle (“'''to the right''', a page proffers a helmet”) which doesn’t matter to the object: it exists from every angle, and it exists independently of whether you view it or not. The focus is on the object, not the viewing. Painting-specific narratives restore that viewing angle. | |||

Painting-specific narratives don’t invent anything. It is known that the concept of object is not necessary to all viewing experiences. They are first a product of abstraction: the object only exists as an object insofar as I can move around it, maybe touch it, or imagine myself doing it, and empirically ascertain that a volume underlies the visuals. By the time someone has intuited the volume, they are already oblivious of the bi-dimensional representation. But the lines and shapes on the surface have their own properties, their own “story.” The fact that the representation of volume and perspective on a flat surface is just an illusion, is only one aspect of the autonomy of the surface. | |||

[[Image:Penrose-dreieck.svg.png|thumb|center|200px|Penrose triangle]] | [[Image:Penrose-dreieck.svg.png|thumb|center|200px|Penrose triangle]] | ||

===== | =====How the perception of uniqueness is biased because of clichés===== | ||

There is nothing trivial or objective in the assumption that all | There is nothing trivial or objective in the assumption that all paintings must be interpreted as representing things. Picasso’s ''Mandolin Player'' might not be the obfuscated representation of a mandolin player. Even if it was, I would argue that it’s not the interesting part. What makes this assembly of geometrical patterns stand out as such, and not just be the equal of the sculpture of a mandolin player, or even the photograph of a mandolin player? | ||

Sure, the overwhelming majority of painters actually wish for people to perceive their work as representations. But the point is not necessarily about the artist’s intention, but the potential of interpretation in general, and how people routinely put a ceiling on it—e.g., in abstract art, when the reviewer attempts, sometimes desperately, to figure out what may lurk behind the | Sure, the overwhelming majority of painters actually wish for people to perceive their work as representations. But the point is not necessarily about the artist’s intention, but the potential of interpretation in general, and how people routinely put a ceiling on it—e.g., in abstract art, when the reviewer attempts, sometimes desperately, to figure out what may lurk behind the abstract: | ||

[[Image:Picasso three musicians moma 2006.jpg|thumb|center|500px|Picasso’s ''Three Musicians'']] | [[Image:Picasso three musicians moma 2006.jpg|thumb|center|500px|Picasso’s ''Three Musicians'']] | ||

| Line 143: | Line 147: | ||

{{quote|Picasso paints three musicians made of flat, brightly colored, abstract shapes in a shallow, boxlike room. On the left is a clarinet player, in the middle a guitar player, and on the right a singer holding sheets of music. They are dressed as familiar figures: Pierrot, wearing a blue and white suit; Harlequinn, in an orange and yellow diamond-pattered custome; and, at right, a friar in a black robe. In front of Pierrot stands a table with a pipe and other objects, while beneath him is a dog, whose belly, legs, and tail peep out behind the musician’s legs. Like the boxy brown stage on which the three musicians perform, everything in this painting is made up of flat shapes. Behind each musician, the light brown floor is in a different place, extending much farther toward the left than the right. Framing the picture, the floor and the flat walls make the room lopsided, but the musicians seem steady. Music Makers in Harmony; It is hard to tell where one musician starts and another stops, because the shapes that create them intersect and overlap, as if they were paper cutouts. Pierrot, the figure in blue and white, holds a clarinet in his hands; one hand is connected to a long, thin, black arm, while the other hand lacks an arm. ''Three Musicians'' emphasizes lively colors, angular shapes, and flat patterns. Picasso said he was delighted when “Gertrude Stein joyfully announced… that she had at last understood what… the three musicians was meant to be. It was a still life!” | {{quote|Picasso paints three musicians made of flat, brightly colored, abstract shapes in a shallow, boxlike room. On the left is a clarinet player, in the middle a guitar player, and on the right a singer holding sheets of music. They are dressed as familiar figures: Pierrot, wearing a blue and white suit; Harlequinn, in an orange and yellow diamond-pattered custome; and, at right, a friar in a black robe. In front of Pierrot stands a table with a pipe and other objects, while beneath him is a dog, whose belly, legs, and tail peep out behind the musician’s legs. Like the boxy brown stage on which the three musicians perform, everything in this painting is made up of flat shapes. Behind each musician, the light brown floor is in a different place, extending much farther toward the left than the right. Framing the picture, the floor and the flat walls make the room lopsided, but the musicians seem steady. Music Makers in Harmony; It is hard to tell where one musician starts and another stops, because the shapes that create them intersect and overlap, as if they were paper cutouts. Pierrot, the figure in blue and white, holds a clarinet in his hands; one hand is connected to a long, thin, black arm, while the other hand lacks an arm. ''Three Musicians'' emphasizes lively colors, angular shapes, and flat patterns. Picasso said he was delighted when “Gertrude Stein joyfully announced… that she had at last understood what… the three musicians was meant to be. It was a still life!” | ||

''Three Musicians'' is an example of Picasso’s Cubist style. In Cubism, the subject of the artwork is transformed into a sequence of planes, lines, and arcs. Cubism has been described as an intellectual style because the artists analyzed the shapes of their subjects and reinvented them on the canvas. The viewer must reconstruct the subject and space of the work by comparing the different shapes and forms to determine what each one represents. Through this process, the viewer participates with the artist in making the artwork make sense. | ''Three Musicians'' is an example of Picasso’s Cubist style. In Cubism, the subject of the artwork is transformed into a sequence of planes, lines, and arcs. Cubism has been described as an intellectual style because the artists analyzed the shapes of their subjects and reinvented them on the canvas. The viewer must reconstruct the subject and space of the work by comparing the different shapes and forms to determine what each one represents. Through this process, the viewer participates with the artist in making the artwork make sense.||pablopicasso.org | ||

| | |||

|pablopicasso.org | |||

|Review of ''Three Musicians'' | |Review of ''Three Musicians'' | ||

}} | }} | ||

The review is figure-centric. It tries to tell “where one musician starts and another stops,” because it has somehow decided that | The review is figure-centric. It tries to tell “where one musician starts and another stops,” because it has somehow decided that the painting was the representation of actual musicians, with a certain idea of anatomical proportions. The analysis projects the concept of figure onto the visuals, effectively subordinating the medium to its preconceptions: the medium can only work '''toward what the viewer already knows'''. The cognitive experience is already prejudiced, even before the viewer has “reconstruct[ed] the subject and space of the work by comparing the different shapes and forms to determine what each one represents.” | ||

In a preconception-free interpretation of visuals, there would be no place for such a thing as confusion and “not making sense.” Only bringing up one’s preconceptions does that. “It is hard to tell where one musician starts and another stops, '''because''' the shapes that create them intersect and | In a preconception-free interpretation of the visuals, there would be no place for such a thing as confusion and “not making sense.” Only bringing up one’s preconceptions does that. “It is hard to tell where one musician starts and another stops, '''because''' the shapes that create them intersect and overlap”: it '''is''' confusing in regard to the expectation of a certain kind of figures, but confusingly enough, the exact way shapes “intersect and overlap” doesn’t suffer any confusion. And the exact way they “intersect and overlap” may precisely be the whole point. If you look at the patches of blue, they induce a kind of dislocated figure: it has a chin borrowed from the white musician, eyes borrowed from the harlequin, and it has legs, too. This figure is a painting-specific recurrence of structure. It doesn’t encumber itself with likelihood. | ||

The classical concept of figure belongs, with other concepts such as history, location, and meaning, to an implicit culture. This culture | The classical concept of figure belongs, with other concepts such as history, location, and meaning, to an implicit culture. This culture is oblivious to painting-specific narratives, favoring instead clichés. The clichés are anticipated, to the point that non-clichés are '''only recognized because we are looking for the clichés'''. In Hans Holbein’s ''The Ambassadors'', Slavoj Žižek calls the bizarre anamorphic skull in the center “the blot”: an inaccessible, obscure object of desire. | ||

[[Image:600px-Hans Holbein the Younger - The Ambassadors - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|center|500px|Hans Holbein’s ''The Ambassadors'']] | [[Image:600px-Hans Holbein the Younger - The Ambassadors - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|center|500px|Hans Holbein’s ''The Ambassadors'']] | ||

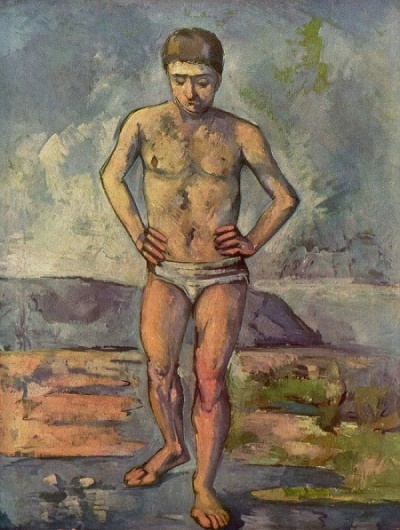

The blot is most unusual, but isn’t it also unusual that in Cézanne’s ''The Nude Bather'', an expanse of mountain in the background runs parallel to the flat ground and slopes off at | The blot is most unusual, but isn’t it also unusual that in Cézanne’s ''The Nude Bather'', an expanse of mountain in the background runs parallel to the flat ground and slopes off in a way that mirrors the shape of the puddle at the bather’s feet? | ||

[[Image:The-bather.jpg|thumb|center|400px|Isn’t the shape of the mountain in relation to the | [[Image:The-bather.jpg|thumb|center|400px|Isn’t the shape and position of the mountain in the background most unusual in relation to the other elements in Cézanne’s ''The Nude Bather'' ?]] | ||

The blot in ''The Ambassadors'' is instantly recognized as such by confronting certain expectations. But in the painting-specific narrative, the fact that it doesn’t play more of a role than any similarly shaped figure would—say, a quill slanting at the same angle—reveals the interpretive bias in both the cliché and the non-cliché. As a manner of speaking, there are “blots” everywhere. Cézanne sought them in vases, fruits, and silver cutlery. Anyone can find blots looking at the racks of vegetables in a supermarket. | |||

Flatness in Modernist painting was, in the beginning, a non-cliché that fed off the clichés. For Clement Greenberg, the “purity” of “[ | Flatness in Modernist painting was, in the beginning, a non-cliché that fed off the clichés. For Clement Greenberg, the “purity” of “[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medium_specificity medium specificity]” is the affirmation of its independence from the figurative: | ||

{{quote|The essence of Modernism lies, as I see it, in the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself, not in order to subvert it but in order to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence. […] | {{quote|The essence of Modernism lies, as I see it, in the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself, not in order to subvert it but in order to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence. […] | ||

It quickly emerged that the unique and proper area of competence of each art coincided with all that was unique in the nature of its medium. The task of self-criticism became to eliminate from the specific effects of each art any and every effect that might conceivably be borrowed from or by the medium of any other art. Thus would each art be rendered “pure,” and in its “purity” find the guarantee of its standards of quality as well as of its independence. “Purity” meant self-definition, and the enterprise of self-criticism in the arts became one of self-definition with a vengeance. | It quickly emerged that the unique and proper area of competence of each art coincided with all that was unique in the nature of its medium. '''The task of self-criticism became to eliminate from the specific effects of each art any and every effect that might conceivably be borrowed from or by the medium of any other art. Thus would each art be rendered “pure,” and in its “purity” find the guarantee of its standards of quality as well as of its independence'''. “Purity” meant self-definition, and the enterprise of self-criticism in the arts became one of self-definition with a vengeance. | ||

Realistic, naturalistic art had dissembled the medium, using art to conceal art; Modernism used art to call attention to art. The limitations that constitute the medium of painting—the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment—were treated by the Old Masters as negative factors that could be acknowledged only implicitly or indirectly. Under Modernism these same limitations came to be regarded as positive factors, and were acknowledged openly. Manet’s became the first Modernist pictures by virtue of the frankness with which they declared the flat surfaces on which they were painted. The Impressionists, in Manet’s wake, abjured underpainting and glazes, to leave the eye under no doubt as to the fact that the colors they used were made of paint that came from tubes or pots. Cézanne sacrificed verisimilitude, or correctness, in order to fit his drawing and design more explicitly to the rectangular shape of the canvas. | Realistic, naturalistic art had dissembled the medium, using art to conceal art; Modernism used art to call attention to art. The limitations that constitute the medium of painting—the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment—were treated by the Old Masters as negative factors that could be acknowledged only implicitly or indirectly. Under Modernism these same limitations came to be regarded as positive factors, and were acknowledged openly. Manet’s became the first Modernist pictures by virtue of the frankness with which they declared the flat surfaces on which they were painted. The Impressionists, in Manet’s wake, abjured underpainting and glazes, to leave the eye under no doubt as to the fact that the colors they used were made of paint that came from tubes or pots. Cézanne sacrificed verisimilitude, or correctness, in order to fit his drawing and design more explicitly to the rectangular shape of the canvas.||Clement Greenberg | ||

| | |||

|Clement Greenberg | |||

|Modernist Painting | |Modernist Painting | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 179: | Line 179: | ||

{{quote|Modernist painting in its latest phase '''has not abandoned the representation of recognizable objects in principle'''. What it has abandoned in principle is the representation of the kind of space that recognizable objects can inhabit. Abstractness, or the non-figurative, has in itself still not proved to be an altogether necessary moment in the self-criticism of pictorial art, even though artists as eminent as Kandinsky and Mondrian have thought so. As such, representation, or illustration, does not attain the uniqueness of pictorial art; what does do so is the associations of things represented. All recognizable entities (including pictures themselves) exist in three-dimensional space, and the barest suggestion of a recognizable entity suffices to call up associations of that kind of space. The fragmentary silhouette of a human figure, or of a teacup, will do so, and by doing so alienate pictorial space from the literal two-dimensionality which is the guarantee of painting’s independence as an art. For, as has already been said, three-dimensionality is the province of sculpture. To achieve autonomy, painting has had above all to divest itself of everything it might share with sculpture, and it is in its effort to do this, and not so much—I repeat—to exclude the representational or literary, that painting has made itself abstract. […] | {{quote|Modernist painting in its latest phase '''has not abandoned the representation of recognizable objects in principle'''. What it has abandoned in principle is the representation of the kind of space that recognizable objects can inhabit. Abstractness, or the non-figurative, has in itself still not proved to be an altogether necessary moment in the self-criticism of pictorial art, even though artists as eminent as Kandinsky and Mondrian have thought so. As such, representation, or illustration, does not attain the uniqueness of pictorial art; what does do so is the associations of things represented. All recognizable entities (including pictures themselves) exist in three-dimensional space, and the barest suggestion of a recognizable entity suffices to call up associations of that kind of space. The fragmentary silhouette of a human figure, or of a teacup, will do so, and by doing so alienate pictorial space from the literal two-dimensionality which is the guarantee of painting’s independence as an art. For, as has already been said, three-dimensionality is the province of sculpture. To achieve autonomy, painting has had above all to divest itself of everything it might share with sculpture, and it is in its effort to do this, and not so much—I repeat—to exclude the representational or literary, that painting has made itself abstract. […] | ||

And I cannot insist enough that '''Modernism has never meant, and does not mean now, anything like a break with the past'''. It may mean a devolution, an unraveling, of tradition, but it also means its further evolution. Modernist art continues the past without gap or break, and wherever it may end up it will never cease being intelligible in terms of the past. […] | And I cannot insist enough that '''Modernism has never meant, and does not mean now, anything like a break with the past'''. It may mean a devolution, an unraveling, of tradition, but it also means its further evolution. Modernist art continues the past without gap or break, and wherever it may end up it will never cease being intelligible in terms of the past. […]||Clement Greenberg | ||

| | |||

|Clement Greenberg | |||

|Modernist Painting | |Modernist Painting | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 193: | Line 191: | ||

}} | }} | ||

Also the ''Postscript'', in which Greenberg defends himself from “advocating” pure art, correlates purity | Also the ''Postscript'', in which Greenberg defends himself from “advocating” pure art, correlates purity with the “very best art of the last hundred-odd years”: | ||

{{quote|I want to take this chance to correct an error, one of interpretation and not of fact. Many readers, though by no means all, seem to have taken the “rationale” of Modernist art outlined here as representing a position adopted by the writer himself that is, that what he describes he also advocates. This may be a fault of the writing or the rhetoric. Nevertheless, a close reading of what he writes will find nothing at all to indicate that he subscribes to, believes in, the things that he adumbrates. (The quotation marks around pure and purity should have been enough to show that.) '''The writer is trying to account in part for how most of the very best art of the last hundred-odd years came about''', but he’s not implying that that’s how it had to come about, much less that that’s how the best art still has to come about. “Pure” art was a useful illusion, but this doesn’t make it any the less an illusion. Nor does the possibility of its continuing usefulness make it any the less an illusion. | {{quote|I want to take this chance to correct an error, one of interpretation and not of fact. Many readers, though by no means all, seem to have taken the “rationale” of Modernist art outlined here as representing a position adopted by the writer himself that is, that what he describes he also advocates. This may be a fault of the writing or the rhetoric. Nevertheless, a close reading of what he writes will find nothing at all to indicate that he subscribes to, believes in, the things that he adumbrates. (The quotation marks around pure and purity should have been enough to show that.) '''The writer is trying to account in part for how most of the very best art of the last hundred-odd years came about''', but he’s not implying that that’s how it had to come about, much less that that’s how the best art still has to come about. “Pure” art was a useful illusion, but this doesn’t make it any the less an illusion. Nor does the possibility of its continuing usefulness make it any the less an illusion. | ||

| Line 201: | Line 199: | ||

}} | }} | ||

This “usefulness” of “pure” art helped propel the “best” art over the lesser art, but there’s a caveat. The claim that the | This “usefulness” of “pure” art helped propel the “best” art over the lesser art, but there’s a caveat. The claim that the best art comes about by emphasizing “the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment” doesn’t actually communicate any demarcation between “best” and lesser art; Greenberg certainly came across pure paintings he found more pointless than others, unless he is to pure paintings what Marilyn Burns of ''Texas Chainsaw Massacre'' fame is to movies, according to this interview: | ||

{{quote|TT: Do you have a favorite? | {{quote|TT: Do you have a favorite? | ||

| Line 219: | Line 217: | ||

}} | }} | ||

Purity isn’t enough of a criterion to demarcate art—at least it hasn’t been for a while, because it’s become a | Purity isn’t enough of a criterion to demarcate great art—at least it hasn’t been for a while, because it’s become a trope. As soon as both pure and non-pure paintings became equally accepted by the public, purity revealed itself to be too coarse as a criterion. In fact, non-pure paintings, even photographs, can be interpreted in terms of “the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment.” I could also “purify” any painting by overlaying it with solid colors, and I certainly wouldn’t expect Greenberg to hang it up there with his so-called “best art.” Likewise, non-pure art, such as photographs, can be interpreted through a purity lens. This photograph from Jay Maisel, ''Damsels wearing face packs posing before panels'', illustrates this: | ||

[[Image:Jay maisel face packs.jpg|thumb|center|400px|Jay Maisel, ''Damsels wearing face packs posing before panels'']] | [[Image:Jay maisel face packs.jpg|thumb|center|400px|Jay Maisel, ''Damsels wearing face packs posing before panels'']] | ||

The | The composition divides the surface into convex regions encompassing each woman. The separation is further accentuated by the panels in the background. It’s particularly formal: | ||

[[Image:Jay maisel face packs marked.png|thumb|center|400px|]] | [[Image:Jay maisel face packs marked.png|thumb|center|400px|]] | ||

To be more accurate, the panels | To be more accurate, the panels accompany the left forearm/elbow of the woman to the right. The left hand of the woman follows the convex shape (dashed red line around her head): | ||

[[Image:Jay maisel face packs marked2.png|thumb|center|400px|]] | [[Image:Jay maisel face packs marked2.png|thumb|center|400px|]] | ||

but the left | but the left forearm/elbow “moves” it in the direction sketched by the contour of the lockers. It is a kind of “mutant” motif derived from the motif created by the face mask (cf. blue highlights). Note how the latter differs from the closed-off face mask of the other woman. | ||

The photograph is obviously figurative. But its formality also ostentates a medium-specific narrative. It isn’t a mere matter of opposition between purity and non-purity. The described medium-specific narrative very specifically relies on connections between elements of human figures: the left hand connecting to the left forearm, the left hand connecting to the shape of the facemask through the color of the skin, and so on. | |||

The interpretation of medium-specific narratives stresses | The interpretation of medium-specific narratives stresses visual patterns and doesn’t see (non)flatness. This remotely echoes the sentiment of certain authors like Deleuze and Guattari, who not only criticize the “order of the signifying and the figure,” but also its opposite, the “pure figural” as a “transgression… that remain[s] secondary nonetheless,” that is, secondary to the “schizophreny as process”: | ||

{{quote|[…] Lyotard shows in very beautiful pages that what is ''operating'' inside the dream is not the signifying, but a figural underneath, producing image configurations that use words, make them flow and traverse them following flows and positions that are not linguistic, without depending on neither the signifying nor its regulated elements. Everywhere, Lyotard destroys the order of the signifying and the figure. Rather than having the figures depend on the signifying and its effects, the signifying chain depends on the figural effects, the chain itself made up of asignifying signs, overwriting the signifying as well as the signified, treating the words like things, fabricating new units, producing, with the help of non-figurative figures, image configurations that ebb and flow […] The element of the pure figural, the “matrix-figure,” Lyotard actually calls it desire, that which leads us to the gates of schizophreny as process. But where does the reader’s impression come from, that Lyotard never ceases to stop the process, to recall the schizes to the shores that he just left, coded or overcoded territories, spaces and structures, '''where they only bring “transgressions,” disorders and distortions that remain secondary nonetheless''', rather than form and carry away the desiring machines that oppose the structures, the intensities that oppose space? Despite his attempt at binding desire to a fundamental yes, Lyotard reintroduces lack and absence in desire, keeps it under the law of castration at the risk of bringing back the whole signifying with it, and discovers the matrix-figure in the fantasm, the mere fantasm that obscures the desiring production, all desire as effective production. | {{quote|[…] Lyotard shows in very beautiful pages that what is ''operating'' inside the dream is not the signifying, but a figural underneath, producing image configurations that use words, make them flow and traverse them following flows and positions that are not linguistic, without depending on neither the signifying nor its regulated elements. Everywhere, Lyotard destroys the order of the signifying and the figure. Rather than having the figures depend on the signifying and its effects, the signifying chain depends on the figural effects, the chain itself made up of asignifying signs, overwriting the signifying as well as the signified, treating the words like things, fabricating new units, producing, with the help of non-figurative figures, image configurations that ebb and flow […] The element of the pure figural, the “matrix-figure,” Lyotard actually calls it desire, that which leads us to the gates of schizophreny as process. But where does the reader’s impression come from, that Lyotard never ceases to stop the process, to recall the schizes to the shores that he just left, coded or overcoded territories, spaces and structures, '''where they only bring “transgressions,” disorders and distortions that remain secondary nonetheless''', rather than form and carry away the desiring machines that oppose the structures, the intensities that oppose space? Despite his attempt at binding desire to a fundamental yes, Lyotard reintroduces lack and absence in desire, keeps it under the law of castration at the risk of bringing back the whole signifying with it, and discovers the matrix-figure in the fantasm, the mere fantasm that obscures the desiring production, all desire as effective production.|[…] dans le rêve, Lyotard montre dans de très belles pages que ce qui ''travaille'' n’est pas le signifiant, mais un figural en dessous, faisant surgir des configurations d’images qui se servent des mots, les font couler et les coupent suivant des flux et des points qui ne sont pas linguistiques, en ne dépendent pas du signifiant ni de ses éléments réglés. Partout donc Lyotard renverse l’ordre du signifiant et de la figure. Ce ne sont pas les figures qui dépendent du signifiant et de ses effets, c’est la chaîne signifiante qui dépend des effets figuraux, faite elle-même de signes asignifiants, écrasant les signifiants comme les signifiés, traîtant les mots comme des choses, fabriquant de nouvelles unités, faisant avec des figures non figuratives des configurations d’images qui se font et se défont. […] L’élément du figural pur, la “figure-matrice,” Lyotard la nomme bien désir, qui nous conduit aux portes de la schizophrénie comme processus. Mais d’où vient pourtant l’impression du lecteur que Lyotard n’a de cesse d’arrêter le processus, et de rabattre les schizes sur les rivages qu’il vient de quitter, territoires codés ou surcodés, espaces et structures, ''''où ils ne font plus qu’apporter des “trangressions,” des troubles et des déformations malgré tout secondaires''', au lieu de former et d’emporter plus loin les machines désirantes qui s’opposent aux structures, les intensités qui s’opposent aux espaces ? C’est que, malgré sa tentative de lier le désir à un oui fondamental, Lyotard réintroduit le manque et l’absence dans le désir, le maintient sous la loi de castration au risque de ramener avec elle tout le signifiant, et découvre la matrice de la figure dans le fantasme, le simple fantasme qui vient occulter la production désirante, tout le désir comme production effective.|Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari | ||

| | |||

[…] dans le rêve, Lyotard montre dans de très belles pages que ce qui ''travaille'' n’est pas le signifiant, mais un figural en dessous, faisant surgir des configurations d’images qui se servent des mots, les font couler et les coupent suivant des flux et des points qui ne sont pas linguistiques, en ne dépendent pas du signifiant ni de ses éléments réglés. Partout donc Lyotard renverse l’ordre du signifiant et de la figure. Ce ne sont pas les figures qui dépendent du signifiant et de ses effets, c’est la chaîne signifiante qui dépend des effets figuraux, faite elle-même de signes asignifiants, écrasant les signifiants comme les signifiés, traîtant les mots comme des choses, fabriquant de nouvelles unités, faisant avec des figures non figuratives des configurations d’images qui se font et se défont. […] L’élément du figural pur, la “figure-matrice,” Lyotard la nomme bien désir, qui nous conduit aux portes de la schizophrénie comme processus. Mais d’où vient pourtant l’impression du lecteur que Lyotard n’a de cesse d’arrêter le processus, et de rabattre les schizes sur les rivages qu’il vient de quitter, territoires codés ou surcodés, espaces et structures, ''''où ils ne font plus qu’apporter des “trangressions,” des troubles et des déformations malgré tout secondaires''', au lieu de former et d’emporter plus loin les machines désirantes qui s’opposent aux structures, les intensités qui s’opposent aux espaces ? C’est que, malgré sa tentative de lier le désir à un oui fondamental, Lyotard réintroduit le manque et l’absence dans le désir, le maintient sous la loi de castration au risque de ramener avec elle tout le signifiant, et découvre la matrice de la figure dans le fantasme, le simple fantasme qui vient occulter la production désirante, tout le désir comme production effective. | |||

|Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari | |||

|Savages, barbarians and civilized men, in ''Anti-Œdipus''}} | |Savages, barbarians and civilized men, in ''Anti-Œdipus''}} | ||

=====Rediscovering graphical narration. A comics-specific narrative from Goossens’ ''Touti and his exhaust pipe''.===== | The interpretation of the medium-specific narrative doesn’t rely on a general theory of art, nor on a theory of the medium such as “medium purity.” It doesn’t rely on a theory of the “very best art of the last hundred-odd years,” either. Any consensus on “the best art” is based on clichés, and the interpretation of the medium-specific narrative doesn’t look for clichés. | ||

=====Rediscovering graphical narration. Real-time sand art as an eye-opener. Graphical narration in movies. A comics-specific narrative from Goossens’ ''Touti and his exhaust pipe''.===== | |||

When it comes to single images, it seems weird to speak of a narrative. But this weirdness is a result of an amnesic way of looking at images. For if one would only be so inclined as to take the placement of a house, the branch of a tree, or the directionality of the texture of a loaf of bread, to be as relevant to the image as death is to a crime novel, one would immediately see the potential of a “graphical story” with multiple heretofore ignored “graphical events.” The events are the visual sensations as our gaze moves across the canvas. Each color transition, each intersection, each pattern can be recorded into a medium-specific narrative, just like storyline events are recorded into the timeline of a regular novel. | |||

These graphical events can be insisted upon through cinematic means: image sequences (polyptichs, comic strips) or animations. In this performace on ''Britain’s Got Talent: The Champions'', Kseniya Simonova uses real-time sand art to tell a 3-minute graphical story. Here, a bird flock progressively morphs into the facial features of a school girl: | |||

[[Image:Sandart0.jpg|center|300px]] | |||

<center>↓</center> | |||

[[Image:Sandart1.jpg|center|300px]] | |||

The sky darkens. Lightning strikes, then it becomes IV lines as the girl gets transposed into a hospital room: | |||

[[Image:Sandart2.jpg|center|300px]] | |||

<center>↓</center> | |||

[[Image:Sandart3.jpg|center|300px]] | |||

This kind of graphics-specific narration is a rarity in movies, even though movies can technically do everything sand art does. Their main focus is on traditional narratives, which is reflected by the fact that many movies are adaptations of written stories. On the other hand, sand art is rather light on story. In our example, the story is actually so cheesy (a child gets hospitalized then recovers, and it all ends with the line “Never give up”) that it would make an embarassing movie without the graphics-specific narrative. It should be noted that the medium specificity emphasized here is graphical and ignores the technicality of performing with sand. By comparison, another cinematic form, shadow play dancing (e.g., the band [https://agt.fandom.com/wiki/Silhouettes Silhouettes] which performed on America’s Got Talent), tends to depict stories that are as cheesy but without the graphics-specific narration, as its focus is more on the technicality of creating mundane shapes with human shadows. | |||

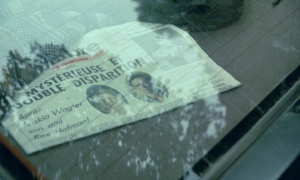

Movies with distinctive medium-specific narratives do exist though, such as ''The Vanishing'' (1988), itself a book adaptation. In that film, a car is inside a tunnel. Inside, a woman, called Saskia, tells her man, Rex Hoffman: | |||

“My nightmare. I had it again last night.” | |||

Hoffman remembers: | |||

“That you’re inside a '''golden egg''', and you can’t get out, and you float all alone through space forever.” | |||

The car runs out of gas inside the tunnel. After a brief argument, Hoffman leaves a panicking Saskia in the car to seek help. When he comes back with a can, she’s not in the car anymore. He drives the car out of the tunnel, and as he emerges, he sees her framed by the bright opening of the tunnel, almost like a golden egg: | |||

[[Image:Thevanishing1.jpg|center|300px]] | |||

At the next rest area, Saskia disappears, probably abducted. Years later, Hoffman still obsesses over her disappearance and does everything in his power to learn what happened to her. On television, he recounts: | |||

“She dreamed that we’d meet somewhere in space, each of us imprisoned inside a golden egg. In my dream, we also found each other, out there in space. And I’ve interpreted this dream as a sign.” | |||

When he finally meets the abductor, he says: | |||

“I don’t want to punish you. I don’t care about you. '''All I want to know is what happened to her'''.” | |||

The abductor agrees to let him know but only under the condition that he lets himself get put into sleep. He accepts after an intense inner debate. He wakes up in the dark and bangs his head while trying to get up. Using a lighter he finds out that he’s stuck inside a coffin. The lighter’s flame fades into the memory of the tunnel opening with Saskia inside: | |||

[[Image:Thevanishing2.jpg|center|300px]] | |||

The last shot of the movie is of a newspaper showing the portraits of Saskia and Hoffman side by side. | |||

[[Image:Thevanishing3.jpg|center|300px]] | |||

Then, a black mask is superimposed over the newspaper, enclosing the portraits inside egg shapes: | |||

[[Image:Thevanishing4.jpg|center|300px]] | |||

A medium-specific narrative therefore leads to fulfilling the golden egg prophecy in a very visual interpretation, from the lighting of the inside of the coffin to the newspaper portraits. Interestingly, the 1993 Hollywood remake, by the same director, takes away the medium-specific narration in favor of action movie tropes. | |||

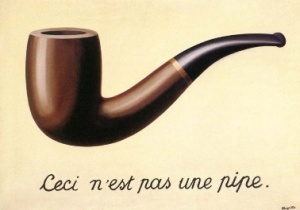

Daniel Goossens’ comic ''Touti and his exhaust pipe'' nicely illustrates the difference between graphical and event-based story-telling. Comics feature two pedagogical advantages over traditional painting: their narrative format, and text. Captions can narrate events, so they can force a break-the-fourth-wall point-of-view onto the reader, leading them to rethink their relationship to the visual medium, often with a comical effect not unlike René Magritte’s ''This is not a pipe''. | |||

[[Image:MagrittePipe.jpg|thumb|center|300px|René Magritte’s ''This is not a pipe'']] | [[Image:MagrittePipe.jpg|thumb|center|300px|René Magritte’s ''This is not a pipe'']] | ||

| Line 253: | Line 302: | ||

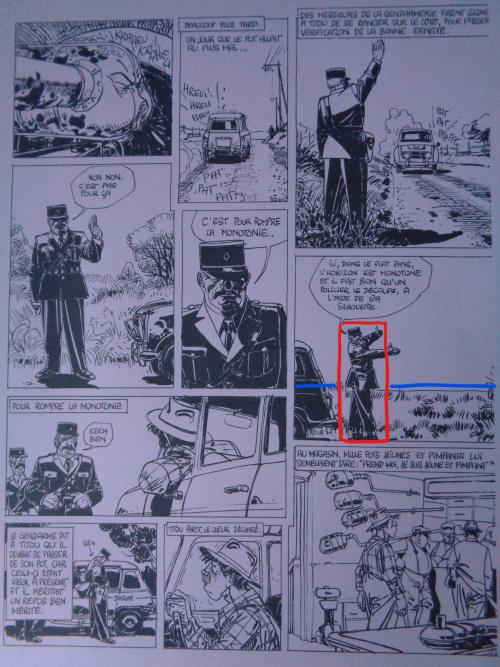

Here’s a page from Goossens’ comics: | Here’s a page from Goossens’ comics: | ||

[[Image:DSC00307. | [[Image:DSC00307.png|thumb|center|500px|Page 2 of Goossens’s ''Touti and his exhaust pipe'']] | ||

The policeman seems to signal Touti to pull over because of | The policeman seems to signal Touti to pull over because of a malfunctioning exhaust pipe, but he corrects the narrator: “No, it’s not for that. It’s to interrupt the monotony. Here, in the flat lands, the horizon [cf. blue highlight] is monotonous, and it is fitting that a policeman cuts through it using his silhouette [cf. red highlight].” | ||

His speech comically emphasizes his '''verticality''' rather than the | His speech (comically) emphasizes his '''verticality''' rather than the concept of “officer of the Law.” The story then builds up toward a car crash: | ||

[[Image:DSC00309. | [[Image:DSC00309.png|thumb|center|500px|Page 3 of Goossens’s ''Touti and his exhaust pipe'']] | ||

Remarkably enough, the car runs into a tree [red highlight] “cutting through the horizon [blue highlight]” just like the vertical officer. A comics-specific narrative thus emerges. | |||

The | The story changes altogether when one switches to a more traditional interpretation. The policeman’s appearance becomes a casual event in the timeline. When all is said and done, all he did was advise Touti to have his exhaust pipe changed. By ending on a car crash, the story expresses the “irony of fate:” at the time of the crash, the car had just been repaired, and to add insult to injury, the tragic turn of events came about due to the advice of the policeman. This interpretation is independent from the graphical representation. For example, seeing the crash from above, instead of having the tree “cut through the horizon,” wouldn’t change the interpretation. There would be a graphically different, but story-wise identical, collision, and a different medium-specific narrative (without the graphical reference to the officer). | ||

====Rediscovering intra-textuality==== | ====Rediscovering intra-textuality==== | ||

| Line 269: | Line 318: | ||

=====Staying inside the text medium: the New Criticism movement. The cliché/non-cliché bias.===== | =====Staying inside the text medium: the New Criticism movement. The cliché/non-cliché bias.===== | ||

Traditionally, interpretation treats prose differently from poetry, poetry differently from | Traditionally, interpretation treats prose differently from poetry, poetry differently from sound poetry, etc. We naturally expect interpretations of poems to be more medium-specific than interpretations of novels, if only because they will be more attentive to text-specific things like phrasal structure, rhyming, and so on: | ||

{{quote|New Criticism developed as a reaction to the older philological and literary history schools, which, influenced by nineteenth-century German scholarship, focused on the history and meaning of individual words and their relation to foreign and ancient languages, comparative sources, and the biographical circumstances of the authors. These approaches, it was felt, tended to distract from the text and meaning of a poem and entirely neglect its aesthetic qualities in favor of teaching about external factors. On the other hand, the literary appreciation school, which limited itself to pointing out the “beauties” and morally elevating qualities of the text, was disparaged by the New Critics as too subjective and emotional. Condemning this as a version of Romanticism, they aimed for newer, systematic and objective method. | {{quote|New Criticism developed as a reaction to the older philological and literary history schools, which, influenced by nineteenth-century German scholarship, focused on the history and meaning of individual words and their relation to foreign and ancient languages, comparative sources, and the biographical circumstances of the authors. These approaches, it was felt, tended to distract from the text and meaning of a poem and entirely neglect its aesthetic qualities in favor of teaching about external factors. On the other hand, the literary appreciation school, which limited itself to pointing out the “beauties” and morally elevating qualities of the text, was disparaged by the New Critics as too subjective and emotional. Condemning this as a version of Romanticism, they aimed for newer, systematic and objective method. | ||

| Line 277: | Line 326: | ||

}} | }} | ||

Just as the | Just as the blot can coerce interpretation in plastic arts, literary content can force the interpreter’s hand. Sound poetry, for example, imposes its own codes: | ||

{{quote|Some consider Mallarmé one of the French poets most difficult to translate into English. The difficulty is due in part to the complex, multilayered nature of much of his work, but also to the important role that the sound of the words, rather than their meaning, plays in his poetry. When recited in French, his poems allow alternative meanings which are not evident on reading the work on the page. For example, Mallarmé’s Sonnet en “-yx” opens with the phrase ses purs ongles (“her pure nails”), whose first syllables when spoken aloud sound very similar to the words c’est pur son (“it’s pure sound”). Indeed, the “pure sound” aspect of his poetry has been the subject of musical analysis and has inspired musical compositions. These phonetic ambiguities are very difficult to reproduce in a translation which must be faithful to the meaning of the words. | {{quote|Some consider Mallarmé one of the French poets most difficult to translate into English. The difficulty is due in part to the complex, multilayered nature of much of his work, but also to the important role that the sound of the words, rather than their meaning, plays in his poetry. When recited in French, his poems allow alternative meanings which are not evident on reading the work on the page. For example, Mallarmé’s ''Sonnet en “-yx”'' opens with the phrase ''ses purs ongles'' (“her pure nails”), whose first syllables when spoken aloud sound very similar to the words ''c’est pur son'' (“it’s pure sound”). Indeed, the “pure sound” aspect of his poetry has been the subject of musical analysis and has inspired musical compositions. These phonetic ambiguities are very difficult to reproduce in a translation which must be faithful to the meaning of the words. | ||

| | | | ||

|English Wikipedia | |English Wikipedia | ||

| | |Stéphane Mallarmé | ||

}} | }} | ||

But | But there’s an interpretive bias as soon as one ignores sound in places we don’t expect it to matter. Such is the case for the final lines of ''Ode on a Grecian Urn'', whose rhyme structure—“Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know”—wasn’t really interpreted by the majority of academics (and at best confused them) who chose instead to debate about the meaning and who truly spoke to whom: poet to reader, urn to reader, poet to urn, poet to figures on the urn? | ||

=====The question of scale: the medium-specific micro-narratives | =====The question of scale: the medium-specific micro-narratives===== | ||

Medium-specific narratives in literature are nothing new. For example, reasoning fallacies offer various forms of medium-specific narratives. What they lack in reality, scientific reliability and applicability, they gain by being amusing, entertaining, witty, comical, interesting, artful, limitless. Syllogistic fallacies could very well be described as | Medium-specific narratives in literature are nothing new. For example, reasoning fallacies offer various forms of medium-specific narratives. What they lack in reality, scientific reliability, and practical applicability, they gain by being amusing, entertaining, witty, comical, interesting, artful, and limitless. Syllogistic fallacies could very well be described as “patterns of resolved stresses,” as the New Criticism describes poetry. “Stress” accrues with each additional premise, and the conclusion resolves the “stress” mostly by “sounding natural:” | ||

# All inhabitants of other planets drink water. | # All inhabitants of other planets drink water. | ||

# All | # All Martians are inhabitants of another planet. | ||

# Therefore, some Martians drink water. | # Therefore, some Martians drink water. | ||

| Line 298: | Line 347: | ||

# All inhabitants of other planets drink water. | # All inhabitants of other planets drink water. | ||

# All | # All Martians are inhabitants of another planet. | ||

# Therefore, among all the beings who drink water, there must exist at least one Martian. | # Therefore, among all the beings who drink water, there must exist at least one Martian. | ||

| Line 307: | Line 356: | ||

# Therefore, my grandfather is a student. | # Therefore, my grandfather is a student. | ||

The fallacy relies on | The fallacy relies on symmetry, both semantically and structurally. Should the premises be very distinct from each other, this wouldn’t even be considered a good fallacy. The following rewrite would be far less convincing: | ||

# All political leaders, doctors and students have been young. | # All political leaders, doctors, and students have been young. | ||

# My grandfather has been young. | # My grandfather has been young. | ||

# So he is a student. | # So he is a student. | ||

In comparison, | In comparison, a rational conclusion is tediously obvious, down-to-earth, tautological, uncomical. | ||

# All political leaders, doctors and students have been young. | # All political leaders, doctors, and students have been young. | ||

# My grandfather has been young. | # My grandfather has been young. | ||

# He may have been a political leader, a doctor and/or a student, but it is not necessary. | # He may have been a political leader, a doctor, and/or a student, but it is not necessary. | ||

Fallacies are not | Fallacies are not just syllogisms that fit into 3 sentences. They routinely occur informally, most unassumingly in scientific literature. The reader doesn’t always need a science degree in order to detect them, because a fallacy, as a medium-specific narrative, can be expressed in the text itself, in a self-contained way. | ||

Not all of science is equally vulnerable to fallacy. Compared to axiomatic science, empirical science as a collection of universal laws (e.g., “the action is always equal to the reaction”) is more “entertaining,” whether because of the leaps of faith that, as Hume pointed out, are required to elevate experimental observations to universal statements, or because of the wishful thinking underneath their justification, especially in the fields of applied science. For example, in ''The Logic of Scientific Discovery'', Popper refutes the argument that his concept of “degree of corroboration of probability hypotheses” is reducible to traditional probability: | |||

{{quote|1=Consider the next throw with a homogeneous die. Let x be the | {{quote|1=Consider the next throw with a homogeneous die. Let x be the statement ‘six will turn up’; let y be its negation, that is to say, let y = ~x; and let z be the information ‘an even number will turn up’. We have the following absolute probabilities: | ||

statement ‘six will turn up’; let y be its negation, that is to say, let y = ~x; and let z be the information ‘an even number will turn up’. We have the following absolute probabilities: | |||

p(x) = 1/6; p(y) = 5/6; p(z) = 1/2. | p(x) = 1/6; p(y) = 5/6; p(z) = 1/2. | ||

| Line 332: | Line 380: | ||

p(x, z) = 1/3; p(y, z) = 2/3. | p(x, z) = 1/3; p(y, z) = 2/3. | ||

We see that x is supported by the information z, for z raises the | We see that x is supported by the information z, for z raises the probability of x from 1/6 to 2/6 = 1/3. We also see that y is undermined by z, for z lowers the probability of y by the same amount from 5/6 to 4/6 = 2/3. Nevertheless, we have p(x, z) < p(y, z). This example proves the following theorem: | ||

probability of x from 1/6 to 2/6 = 1/3. We also see that y is undermined by z, for z lowers the probability of y by the same amount from 5/6 to 4/6 = 2/3. Nevertheless, we have p(x, z) < p(y, z). This example proves the following theorem: | |||

(5) There exist statements, x, y, and z, which satisfy the formula, | (5) There exist statements, x, y, and z, which satisfy the formula, | ||

| Line 341: | Line 388: | ||

Obviously, we may replace here ‘p(y, z) < p(y)’ by the weaker ‘p(y, z) ≤ p(y)’. | Obviously, we may replace here ‘p(y, z) < p(y)’ by the weaker ‘p(y, z) ≤ p(y)’. | ||

This theorem is, of course, far from being paradoxical. And the same | This theorem is, of course, far from being paradoxical. And the same holds for its corollary (6) which we obtain by substituting for ‘p(x, z) > p(x)’ and ‘p(y, z) ≤ p(y)’ the expressions ‘Co(x, z)’ and ‘¬Co(y, z)’—that is to say ‘non-Co(y, z)’—respectively, in accordance with formula (1) above: | ||

holds for its corollary (6) which we obtain by substituting for | |||

‘p(x, z) > p(x)’ and ‘p(y, z) ≤ p(y)’ the expressions ‘Co(x, z)’ and | |||

‘¬Co(y, z)’—that is to say ‘non-Co(y, z)’—respectively, in accordance | |||

with formula (1) above: | |||

(6) There exist statements x, y and z which satisfy the formula | (6) There exist statements x, y and z which satisfy the formula | ||

| Line 351: | Line 394: | ||

Co(x, z) & ¬Co(y, z) & p(x, z) < p(y, z). | Co(x, z) & ¬Co(y, z) & p(x, z) < p(y, z). | ||

Like (5), theorem (6) expresses a fact we have established by our | Like (5), theorem (6) expresses a fact we have established by our example: that x may be supported by z, and y undermined by z, and that nevertheless x, given z, may be less probable than y, given z. There at once arises, however, a clear self-contradiction if we now identify in (6) degree of confirmation C(a, b) and probability p(a, b). In other words, the formula | ||

example: that x may be supported by z, and y undermined by z, and that | |||

nevertheless x, given z, may be less probable than y, given z. | |||

There at once arises, however, a clear self-contradiction if we now | |||

identify in (6) degree of confirmation C(a, b) and probability p(a, b). In | |||

other words, the formula | |||

(**) Co(x, z) & ¬Co(y, z) & C(x, z) < C(y, z) | (**) Co(x, z) & ¬Co(y, z) & C(x, z) < C(y, z) | ||

(that is, ‘z confirms x but not y, yet z also confirms x to a lesser degree | (that is, ‘z confirms x but not y, yet z also confirms x to a lesser degree than y’) is clearly self-contradictory. | ||

than y’) is clearly self-contradictory. | |||

Thus we have proved that the identification of degree of corroboration or confirmation with probability (and even with likelihood) is absurd on both formal and intuitive grounds: it leads to self-contradiction. | Thus we have proved that the identification of degree of corroboration or confirmation with probability (and even with likelihood) is absurd on both formal and intuitive grounds: it leads to self-contradiction. | ||

| Line 369: | Line 406: | ||

Evidence, and Statistical Tests, in ''The Logic of Scientific Discovery''}} | Evidence, and Statistical Tests, in ''The Logic of Scientific Discovery''}} | ||

However formula (**) is not necessarily self-contradictory, both on intuitive and mathematical grounds. Let’s see why. | However, formula (**) is not necessarily self-contradictory, both on intuitive and mathematical grounds. Let’s see why. | ||

Popper provides a metaphor for formula (**): “x has the property P (for example, the property ‘warm’) and y has not the property P and y has the property P in a higher degree than x (for example, y is warmer than x).” Put like this, (**) certainly seems self-contradictory. | Popper provides a metaphor for formula (**): “x has the property P (for example, the property ‘warm’) and y has not the property P and y has the property P in a higher degree than x (for example, y is warmer than x).” Put like this, (**) certainly seems self-contradictory. | ||

But Popper is misleading when he equates C(x, z) < C(y, z) to “y has the property P in a higher degree than x,” because by definition, this would mean we have “p(y, z) > p(y) to a higher degree than p(x, z) > p(x).” We are comparing | But Popper is misleading when he equates C(x, z) < C(y, z) to “y has the property P in a higher degree than x,” because by definition, this would mean we have “p(y, z) > p(y) to a higher degree than p(x, z) > p(x).” We are comparing 2 statements (“p(y, z) > p(y)” on one hand, and “p(x, z) > p(x)” on the other) each with a different right-hand side, namely p(x) and p(y). I can say that Alice is taller than Bob in a higher degree than Cedric is taller than David, but it’s not contradictory to say that Cedric is taller than Alice. | ||

So a more accurate metaphor for P would be “warmer” rather than just “warm,” with an important emphasis on warmer '''than | So a more accurate metaphor for P would be “warmer” rather than just “warm,” with an important emphasis on warmer '''than something'''. Obviously, if x gets warmer (Co(x, z)) and y cooler (¬Co(y, z)), y can still be warmer than x because it was very hot to start with, so having C(x, z) < C(y, z) (“y is warmer than something, to a higher degree than x is warmer than something”) doesn’t seem contradictory anymore. | ||

Such losses in metaphor share with syllogisms the same propensity | Such losses in metaphor share with syllogisms the same propensity for erasing structural relationships through “honest mistakes” such as the shortcut from “warmer” to “warm.” They underly an infinite number of unique narratives that occur when translating back and forth between informal and formal language. Popper himself debunks Heisenberg’s use of informal language in what belongs to the long list of sensationalist interpretations of numbers and formulas that theoretical physics is especially fond of (e.g., the many-worlds interpretation, Schrödinger’s cat, time dilation): | ||