Book/The Medium-Specific Narrative

Interpretation of the medium-specific narrative

The alternative to the interpretation of the average value is what, in the absence of a more marketable expression, I call the “interpretation of the medium-specific narrative.” The medium-specific narratives are the opposite of the mosaics. Instead of a loose whole, one searches for some tightly-knit structure, with all extras removed. A work contains many medium-specific narratives that may overlap. There may not even be a “the one” medium-specific narrative that the creator is supposed to have designed and intended for their audience. The existence of “the one” is best left to speculative (and ultimately sterile) endeavours. Some narrative may look like it, but in general, the medium-specific narratives are modest in scope and fundamentally hedonistic: the satisfaction of finding one is purely subjective.

The expression “interpretation of the medium-specific narrative” (non-plural) as used in this essay is somewhat misleading. It actually means an interpretation that reveals one of the medium-specific narratives of the interpreted content. You can think of “the medium-specific narrative” as the content itself, and the “interpretation” as a medium-specific sub-narrative that results from a filtering of “the medium-specifc narrative”.

Narrative interpretation is an endeavor to view a work as, broadly speaking, a “story,” i.e., every element in the work is viewed in light of previous elements, the premises or context. If the elements form a succession of events in the same timeline, characters, locations, etc., then we recognize the traditional concept of story. But if the elements are the regions of a painting or the motifs of a musical piece, the concepts of “story” and “premise” take on a peculiar quality relative to the nature of the medium. In a pop song, an element could be a section, for example the chorus, and its premise could be the verse. Depending on the merits of doing so, one could look at a more granular level where an element could mean a phrase, the segment of a phrase, or even a note. Such an element can be seen as the premise to any other element that follows it in the song. In a painting, an “element” could, for example, mean a painted region, an object, or a motif. The concept of “premise” here can be somewhat misleading, as there isn’t a declared timeline. In this case, I like to generalize the definition of “premise” to mean “another element of the painting” which both gives it context and is given a context by it, depending on which element you view as the premise. The elements of a painting implicitly bond together through an implicit timeline, which is the timeline of the viewing experience. The movement of the viewer’s gaze from one region of the painting to another creates a subjective timeline of perceptions, a “story” of perceptions. This timeline tends to be ignored because the observer tends to compress it during the cognitive process—e.g., when we see a portrait, we recognize the face almost instantaneously, without going over the facial features individually. We’ll later see how this “photographic memory” can prejudice visual media.

The physical frame of the narrative (the canvas, the pages, or the sound track) is a convention. It narrows the search for narratives. But you could imagine looking for (and finding) medium-specific narratives in Nature or in any unintended arrangement of objects. This has important ramifications for how one looks at conventional art. The focus is now on the perceptions as they happen to the observer, not as they are intended by some intelligent being. In fact, the medium-specific narratives don’t refer to an external intelligent being at all, since it is outside the medium. On the other hand, a mosaic is the result when one talks of such an intelligent being, a Creator or Artist, in relation to the work.

The “medium specificity” of the narrative means that the elements of the narrative are homogeneous parts of the same medium. In other words, the narrative stays intra-medium. It is an interpretation of a content as a self-contained unit, filtering perceptions happening on a closed timeline (not the timeline of a story in the traditional sense). As a medium-specific narrative, a song is a succession of perceptions (melodies, harmonies, notes, and so on) and nothing else. By contrast, the interpretation of the average value results in a mosaic of features, including mood, theme, genre, and so on. Therefore, the listener first experiences the elements of medium-specific narratives. Considerations like theme or genre are high-level interpretations of these elements.

The mosaic as the medium-specific narrative of reviews

The interpretation of the average value reveals itself when one begins to analyze reviews, and more particularly their narrative structure (or rather the lack thereof), rather than just their supposed usefulness. In a way, reviews are works about works, using a stylistically distinctive thought process that builds upon content through an amnesic process. As such, the reviews have their own medium-specific narratives, of which the mosaic is the invariant. We saw an example through the interpretation of a modern art review.

More generally, medium-specific narratives are not confined to art. In terms of methodology, their interpretation doesn’t make any distinction between art and science, between fiction and non-fiction, between review and reviewed content. In fact, most critiques and analyses you will find in this text are interpretations of the medium-specific narratives of various papers, books, discourses, reviews, and everyday chatter. The interpretations are presented rather informally for the ease of reading, while staying recognizable by the characteristic minuteness with which they capture medium-specific intricacies.

A medium-specific narrative from John Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn. Interpretation writing styles

I chose John Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn because it is short and well-established in academic circles.

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time, Sylvan historian, who canst thus express A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme: What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape Of deities or mortals, or of both, In Tempe or the dales of Arcady? What men or gods are these? What maidens loth? What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d, Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone: Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare; Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss, Though winning near the goal yet, do not grieve; She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss, For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu; And, happy melodist, unwearied, For ever piping songs for ever new; More happy love! more happy, happy love! For ever warm and still to be enjoy’d, For ever panting, and for ever young; All breathing human passion far above, That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy’d, A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.

Who are these coming to the sacrifice? To what green altar, O mysterious priest, Lead’st thou that heifer lowing at the skies, And all her silken flanks with garlands drest? What little town by river or sea shore, Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel, Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn? And, little town, thy streets for evermore Will silent be; and not a soul to tell Why thou art desolate, can e’er return.

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede Of marble men and maidens overwrought, With forest branches and the trodden weed; Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral! When old age shall this generation waste, Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” ❞When I look for a medium-specific narrative, I try to find one that roughly covers the whole work, one that justifies the work as a unit. Here’s one:

- The narrator questions a silent “thou.”

- The narrator associates the silent (“those unheard are sweeter”) with the eternal (“canst not leave […] nor ever,” “never, never”, “For ever,” etc.).

- The eternal is then associated with repetitions of “happy” framed between assonant words (“Ah, happy, happy boughs!”, “More happy love! more happy, happy love!”).

- Finally, when the eternally silent (“Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought as doth eternity”) says something, it addresses the narrator’s questioning (“all ye need to know”) through structures of repetiton, reminiscent of the framed repetitions of “happy”: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

All the terms of the interpretations are reused and combined in different contexts. In (1), the “silent thou” is asked questions which are addressed in (4). The repetitions of the answer “beauty is truth, truth beauty” echo the repetitions of the words happy and love in (3), but in a non-silent context which contrasts the silence in (1) and (2). A narrative thus emerges.

This narrative is medium-specific in the sense that it takes elements directly from the poem with almost no recourse to subjective interpretation. I say almost, because there is certainly some layer of interpretation there. I did skip many details, even entire parts of the poem. I also didn’t mention the stanza structure or the rhyme schemes. Implicit in these oversights is an assessment that they weren’t needed in the narrative I wanted to highlight. If you study the stanza structure or the poem’s themes, as most scholars do, you get invariants rather than a narrative. But this choice, to prefer this poem-wide narrative over invariants, is already an act of subjective interpretation, even if, in the last analysis, I just highlighted certain passages of the poem and their relationships.

I could cook the interpretation a little bit, as it is a little too raw as it is. I could add some commentary that would express the feelings and value judgments that led me to this narrative. I could say this:

« John Keats thus makes us realize that our questionings are superfluous, in the sense that the answer was already implied in the narrator’s enthusiastic exuberance. The answer is in the rythmic expressivity—whether in the questioning itself (the series of “what”) or in the insistence on eternity, happiness and love—that seems to anticipate T.S. Eliot’s criticism of the “grammatically meaningless” statement that “beauty is truth, truth beauty.” »

I will usually choose to stay away from this style of writing, but this is a purely personal choice. I personally like to address an audience that doesn’t need to be spoon-fed and will arrive at its own conclusions. In fact, I would argue that the raw interpretation doesn’t need any conclusion. The elements of the narrative are interlinked with one another in such a way that the whole point is lost as soon as one tries to wrap things up in a generic conclusion—i.e., the narrative is self-contained and self-conclusive, somewhat like “beauty is truth, truth beauty” is self-contained and self-conclusive. In fact, any type of value-based conclusion would attract the sort of (rightful) criticism against awkward attempts at penetrating non-objective concepts through objective interpretation—cf. Derrida’s criticism of Jean Rousset who tried to describe passion in literature (or at least invite his readers to sense it) using only geometrical concepts like “rings,” “symmetry,” “helices,” and so on:

But what does this essay actually tell us? Only the geometry of a theater which is, however, “that of the mad passion, of the heroic enthusiasm.” Not only does the geometrical structure of Polyeucte mobilize all the resources and attention of the author, but the whole teleology of Corneille’s trajectory is attached to it.

❞Mais que nous livre en fait cet essai? La seule géométrie d’un théâtre qui est pourtant “celui de la passion folle, de l’enthousiasme héroïque”. Non seulement la structure géométrique de Polyeucte mobilise toutes les ressources et toute l’attention de l’auteur, mais à elle est ordonnée toute une téléologie de l’itinéraire cornélien.

❞Rediscovering intra-medium movement

Rediscovering intra-visuality. Restoring the primacy of the viewing angle.

Keeping the interpretation intra-medium is counter-intuitive to most of us. “This painting represents the king”: this is a very natural statement to read, though it is hardly concerned with the objective content. If the reader of the statement sticks to what the interpretation actually communicates, and tries to visualize a painting entirely through it, they would imagine a king sitting on a throne, a crown, maybe a heraldic symbol. The visuals, along with all the non-visual facts (including the fact that the king is represented), contribute a “story” that goes beyond the mere visuals.

Such stories are independent of the visuals but it is assumed that these stories “merge” with the visuals and serve their meaning and, ultimately, value. They build a viewerless world:

In the viewerless world signified by the painting, the king is not just a bi-dimensional figure on a surface. The work could very well be a sculpture without invalidating a single word of the interpretation, down to the smallest detail:

The interpretation quoted above captures a viewable object in a particular viewing angle (“to the right, a page proffers a helmet”) which doesn’t matter to the object: it exists from every angle, and it exists independently of whether you view it or not. The focus is on the object, not the viewing. Painting-specific narratives restore that viewing angle.

Painting-specific narratives don’t invent anything. It is known that the concept of object is not necessary to all viewing experiences. They are first a product of abstraction: the object only exists as an object insofar as I can move around it, maybe touch it, or imagine myself doing it, and empirically ascertain that a volume underlies the visuals. By the time someone has intuited the volume, they are already oblivious of the bi-dimensional representation. But the lines and shapes on the surface have their own properties, their own “story.” The fact that the representation of volume and perspective on a flat surface is just an illusion, is only one aspect of the autonomy of the surface.

How the perception of uniqueness is biased because of clichés

There is nothing trivial or objective in the assumption that all paintings must be interpreted as representing things. Picasso’s Mandolin Player might not be the obfuscated representation of a mandolin player. Even if it was, I would argue that it’s not the interesting part. What makes this assembly of geometrical patterns stand out as such, and not just be the equal of the sculpture of a mandolin player, or even the photograph of a mandolin player?

Sure, the overwhelming majority of painters actually wish for people to perceive their work as representations. But the point is not necessarily about the artist’s intention, but the potential of interpretation in general, and how people routinely put a ceiling on it—e.g., in abstract art, when the reviewer attempts, sometimes desperately, to figure out what may lurk behind the abstract:

The review is figure-centric. It tries to tell “where one musician starts and another stops,” because it has somehow decided that the painting was the representation of actual musicians, with a certain idea of anatomical proportions. The analysis projects the concept of figure onto the visuals, effectively subordinating the medium to its preconceptions: the medium can only work toward what the viewer already knows. The cognitive experience is already prejudiced, even before the viewer has “reconstruct[ed] the subject and space of the work by comparing the different shapes and forms to determine what each one represents.”

In a preconception-free interpretation of the visuals, there would be no place for such a thing as confusion and “not making sense.” Only bringing up one’s preconceptions does that. “It is hard to tell where one musician starts and another stops, because the shapes that create them intersect and overlap”: it is confusing in regard to the expectation of a certain kind of figures, but confusingly enough, the exact way shapes “intersect and overlap” doesn’t suffer any confusion. And the exact way they “intersect and overlap” may precisely be the whole point. If you look at the patches of blue, they induce a kind of dislocated figure: it has a chin borrowed from the white musician, eyes borrowed from the harlequin, and it has legs, too. This figure is a painting-specific recurrence of structure. It doesn’t encumber itself with likelihood.

The classical concept of figure belongs, with other concepts such as history, location, and meaning, to an implicit culture. This culture is oblivious to painting-specific narratives, favoring instead clichés. The clichés are anticipated, to the point that non-clichés are only recognized because we are looking for the clichés. In Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors, Slavoj Žižek calls the bizarre anamorphic skull in the center “the blot”: an inaccessible, obscure object of desire.

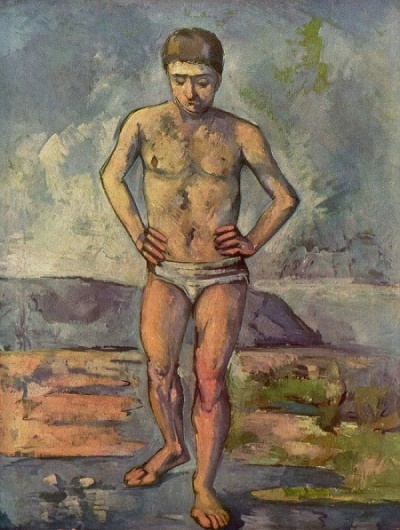

The blot is most unusual, but isn’t it also unusual that in Cézanne’s The Nude Bather, an expanse of mountain in the background runs parallel to the flat ground and slopes off in a way that mirrors the shape of the puddle at the bather’s feet?

The blot in The Ambassadors is instantly recognized as such by confronting certain expectations. But in the painting-specific narrative, the fact that it doesn’t play more of a role than any similarly shaped figure would—say, a quill slanting at the same angle—reveals the interpretive bias in both the cliché and the non-cliché. As a manner of speaking, there are “blots” everywhere. Cézanne sought them in vases, fruits, and silver cutlery. Anyone can find blots looking at the racks of vegetables in a supermarket.

Flatness in Modernist painting was, in the beginning, a non-cliché that fed off the clichés. For Clement Greenberg, the “purity” of “medium specificity” is the affirmation of its independence from the figurative:

It quickly emerged that the unique and proper area of competence of each art coincided with all that was unique in the nature of its medium. The task of self-criticism became to eliminate from the specific effects of each art any and every effect that might conceivably be borrowed from or by the medium of any other art. Thus would each art be rendered “pure,” and in its “purity” find the guarantee of its standards of quality as well as of its independence. “Purity” meant self-definition, and the enterprise of self-criticism in the arts became one of self-definition with a vengeance.

Realistic, naturalistic art had dissembled the medium, using art to conceal art; Modernism used art to call attention to art. The limitations that constitute the medium of painting—the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment—were treated by the Old Masters as negative factors that could be acknowledged only implicitly or indirectly. Under Modernism these same limitations came to be regarded as positive factors, and were acknowledged openly. Manet’s became the first Modernist pictures by virtue of the frankness with which they declared the flat surfaces on which they were painted. The Impressionists, in Manet’s wake, abjured underpainting and glazes, to leave the eye under no doubt as to the fact that the colors they used were made of paint that came from tubes or pots. Cézanne sacrificed verisimilitude, or correctness, in order to fit his drawing and design more explicitly to the rectangular shape of the canvas. ❞But this purity co-exists with non-Modernism, just as we saw in Picasso’s particular style of “figure”: structure, through placement and color rather than volume, fulfills the Modernist part, and the figurative quality fulfills the non-Modernist part. Greenberg himself admits as much:

This attachment to tradition does not prevent “purity” from serving as a “just, good, and relevant reason for appreciating masters”:

Also the Postscript, in which Greenberg defends himself from “advocating” pure art, correlates purity with the “very best art of the last hundred-odd years”:

This “usefulness” of “pure” art helped propel the “best” art over the lesser art, but there’s a caveat. The claim that the best art comes about by emphasizing “the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment” doesn’t actually communicate any demarcation between “best” and lesser art; Greenberg certainly came across pure paintings he found more pointless than others, unless he is to pure paintings what Marilyn Burns of Texas Chainsaw Massacre fame is to movies, according to this interview:

MB: They’re all favorites. I used to watch horror films on Saturday mornings. I like them all. I’m like you guys. You've got more films on your website than I know! And I thought I used to have the category down…

TT: Thank you! Which genre do you enjoy the most?

MB: I like it all. I like mysteries, suspense, horror, comedy, historical… I run the whole gamut. It’s all wonderful.

TT: Have a favorite movie?

MB: I don’t know… I can’t name favorites because I like them all.

❞Purity isn’t enough of a criterion to demarcate great art—at least it hasn’t been for a while, because it’s become a trope. As soon as both pure and non-pure paintings became equally accepted by the public, purity revealed itself to be too coarse as a criterion. In fact, non-pure paintings, even photographs, can be interpreted in terms of “the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment.” I could also “purify” any painting by overlaying it with solid colors, and I certainly wouldn’t expect Greenberg to hang it up there with his so-called “best art.” Likewise, non-pure art, such as photographs, can be interpreted through a purity lens. This photograph from Jay Maisel, Damsels wearing face packs posing before panels, illustrates this:

The composition divides the surface into convex regions encompassing each woman. The separation is further accentuated by the panels in the background. It’s particularly formal:

To be more accurate, the panels accompany the left forearm/elbow of the woman to the right. The left hand of the woman follows the convex shape (dashed red line around her head):

but the left forearm/elbow “moves” it in the direction sketched by the contour of the lockers. It is a kind of “mutant” motif derived from the motif created by the face mask (cf. blue highlights). Note how the latter differs from the closed-off face mask of the other woman.

The photograph is obviously figurative. But its formality also ostentates a medium-specific narrative. It isn’t a mere matter of opposition between purity and non-purity. The described medium-specific narrative very specifically relies on connections between elements of human figures: the left hand connecting to the left forearm, the left hand connecting to the shape of the facemask through the color of the skin, and so on.

The interpretation of medium-specific narratives stresses visual patterns and doesn’t see (non)flatness. This remotely echoes the sentiment of certain authors like Deleuze and Guattari, who not only criticize the “order of the signifying and the figure,” but also its opposite, the “pure figural” as a “transgression… that remain[s] secondary nonetheless,” that is, secondary to the “schizophreny as process”:

The interpretation of the medium-specific narrative doesn’t rely on a general theory of art, nor on a theory of the medium such as “medium purity.” It doesn’t rely on a theory of the “very best art of the last hundred-odd years,” either. Any consensus on “the best art” is based on clichés, and the interpretation of the medium-specific narrative doesn’t look for clichés.

Rediscovering graphical narration. Real-time sand art as an eye-opener. Graphical narration in movies. A comics-specific narrative from Goossens’ Touti and his exhaust pipe.

When it comes to single images, it seems weird to speak of a narrative. But this weirdness is a result of an amnesic way of looking at images. For if one would only be so inclined as to take the placement of a house, the branch of a tree, or the directionality of the texture of a loaf of bread, to be as relevant to the image as death is to a crime novel, one would immediately see the potential of a “graphical story” with multiple heretofore ignored “graphical events.” The events are the visual sensations as our gaze moves across the canvas. Each color transition, each intersection, each pattern can be recorded into a medium-specific narrative, just like storyline events are recorded into the timeline of a regular novel.

These graphical events can be insisted upon through cinematic means: image sequences (polyptichs, comic strips) or animations. In this performace on Britain’s Got Talent: The Champions, Kseniya Simonova uses real-time sand art to tell a 3-minute graphical story. Here, a bird flock progressively morphs into the facial features of a school girl:

The sky darkens. Lightning strikes, then it becomes IV lines as the girl gets transposed into a hospital room:

This kind of graphics-specific narration is a rarity in movies, even though movies can technically do everything sand art does. Their main focus is on traditional narratives, which is reflected by the fact that many movies are adaptations of written stories. On the other hand, sand art is rather light on story. In our example, the story is actually so cheesy (a child gets hospitalized then recovers, and it all ends with the line “Never give up”) that it would make an embarassing movie without the graphics-specific narrative. It should be noted that the medium specificity emphasized here is graphical and ignores the technicality of performing with sand. By comparison, another cinematic form, shadow play dancing (e.g., the band Silhouettes which performed on America’s Got Talent), tends to depict stories that are as cheesy but without the graphics-specific narration, as its focus is more on the technicality of creating mundane shapes with human shadows.

Movies with distinctive medium-specific narratives do exist though, such as The Vanishing (1988), itself a book adaptation. In that film, a car is inside a tunnel. Inside, a woman, called Saskia, tells her man, Rex Hoffman:

“My nightmare. I had it again last night.”

Hoffman remembers:

“That you’re inside a golden egg, and you can’t get out, and you float all alone through space forever.”

The car runs out of gas inside the tunnel. After a brief argument, Hoffman leaves a panicking Saskia in the car to seek help. When he comes back with a can, she’s not in the car anymore. He drives the car out of the tunnel, and as he emerges, he sees her framed by the bright opening of the tunnel, almost like a golden egg:

At the next rest area, Saskia disappears, probably abducted. Years later, Hoffman still obsesses over her disappearance and does everything in his power to learn what happened to her. On television, he recounts:

“She dreamed that we’d meet somewhere in space, each of us imprisoned inside a golden egg. In my dream, we also found each other, out there in space. And I’ve interpreted this dream as a sign.”

When he finally meets the abductor, he says:

“I don’t want to punish you. I don’t care about you. All I want to know is what happened to her.”

The abductor agrees to let him know but only under the condition that he lets himself get put into sleep. He accepts after an intense inner debate. He wakes up in the dark and bangs his head while trying to get up. Using a lighter he finds out that he’s stuck inside a coffin. The lighter’s flame fades into the memory of the tunnel opening with Saskia inside:

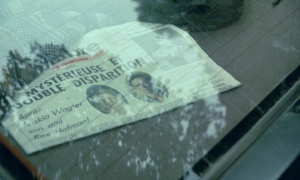

The last shot of the movie is of a newspaper showing the portraits of Saskia and Hoffman side by side.

Then, a black mask is superimposed over the newspaper, enclosing the portraits inside egg shapes:

A medium-specific narrative therefore leads to fulfilling the golden egg prophecy in a very visual interpretation, from the lighting of the inside of the coffin to the newspaper portraits. Interestingly, the 1993 Hollywood remake, by the same director, takes away the medium-specific narration in favor of action movie tropes.

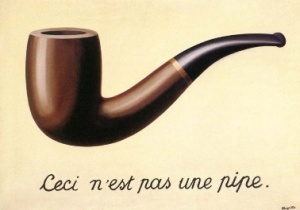

Daniel Goossens’ comic Touti and his exhaust pipe nicely illustrates the difference between graphical and event-based story-telling. Comics feature two pedagogical advantages over traditional painting: their narrative format, and text. Captions can narrate events, so they can force a break-the-fourth-wall point-of-view onto the reader, leading them to rethink their relationship to the visual medium, often with a comical effect not unlike René Magritte’s This is not a pipe.

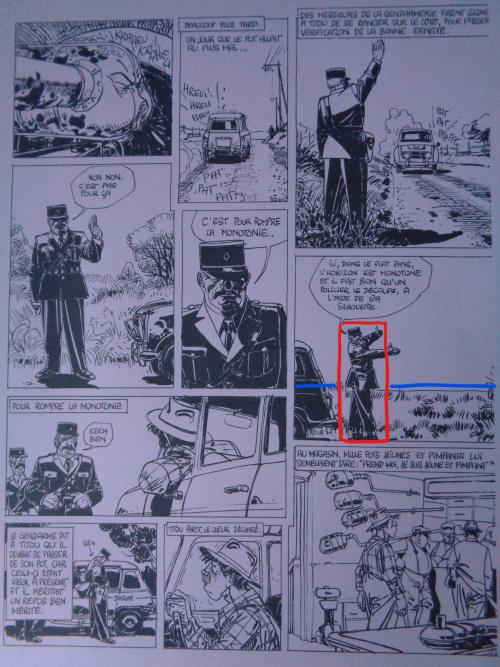

Here’s a page from Goossens’ comics:

The policeman seems to signal Touti to pull over because of a malfunctioning exhaust pipe, but he corrects the narrator: “No, it’s not for that. It’s to interrupt the monotony. Here, in the flat lands, the horizon [cf. blue highlight] is monotonous, and it is fitting that a policeman cuts through it using his silhouette [cf. red highlight].”

His speech (comically) emphasizes his verticality rather than the concept of “officer of the Law.” The story then builds up toward a car crash:

Remarkably enough, the car runs into a tree [red highlight] “cutting through the horizon [blue highlight]” just like the vertical officer. A comics-specific narrative thus emerges.

The story changes altogether when one switches to a more traditional interpretation. The policeman’s appearance becomes a casual event in the timeline. When all is said and done, all he did was advise Touti to have his exhaust pipe changed. By ending on a car crash, the story expresses the “irony of fate:” at the time of the crash, the car had just been repaired, and to add insult to injury, the tragic turn of events came about due to the advice of the policeman. This interpretation is independent from the graphical representation. For example, seeing the crash from above, instead of having the tree “cut through the horizon,” wouldn’t change the interpretation. There would be a graphically different, but story-wise identical, collision, and a different medium-specific narrative (without the graphical reference to the officer).

Rediscovering intra-textuality

Staying inside the text medium: the New Criticism movement. The cliché/non-cliché bias.

Traditionally, interpretation treats prose differently from poetry, poetry differently from sound poetry, etc. We naturally expect interpretations of poems to be more medium-specific than interpretations of novels, if only because they will be more attentive to text-specific things like phrasal structure, rhyming, and so on:

Just as the blot can coerce interpretation in plastic arts, literary content can force the interpreter’s hand. Sound poetry, for example, imposes its own codes:

But there’s an interpretive bias as soon as one ignores sound in places we don’t expect it to matter. Such is the case for the final lines of Ode on a Grecian Urn, whose rhyme structure—“Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know”—wasn’t really interpreted by the majority of academics (and at best confused them) who chose instead to debate about the meaning and who truly spoke to whom: poet to reader, urn to reader, poet to urn, poet to figures on the urn?

The question of scale: the medium-specific micro-narratives

Medium-specific narratives in literature are nothing new. For example, reasoning fallacies offer various forms of medium-specific narratives. What they lack in reality, scientific reliability, and practical applicability, they gain by being amusing, entertaining, witty, comical, interesting, artful, and limitless. Syllogistic fallacies could very well be described as “patterns of resolved stresses,” as the New Criticism describes poetry. “Stress” accrues with each additional premise, and the conclusion resolves the “stress” mostly by “sounding natural:”

- All inhabitants of other planets drink water.

- All Martians are inhabitants of another planet.

- Therefore, some Martians drink water.

The symmetric quality of the transition from “All inhabitants of other planets drink water” to “Therefore, some Martians drink water,” in both sentence structure and word usage, plays no small part in the efficiency of the argumentation. Rewriting the conclusion into a less symmetric form would go a long way toward exposing the fallacy:

- All inhabitants of other planets drink water.

- All Martians are inhabitants of another planet.

- Therefore, among all the beings who drink water, there must exist at least one Martian.

Consider another example:

- All students have been young.

- My grandfather has been young.

- Therefore, my grandfather is a student.

The fallacy relies on symmetry, both semantically and structurally. Should the premises be very distinct from each other, this wouldn’t even be considered a good fallacy. The following rewrite would be far less convincing:

- All political leaders, doctors, and students have been young.

- My grandfather has been young.

- So he is a student.

In comparison, a rational conclusion is tediously obvious, down-to-earth, tautological, uncomical.

- All political leaders, doctors, and students have been young.

- My grandfather has been young.

- He may have been a political leader, a doctor, and/or a student, but it is not necessary.

Fallacies are not just syllogisms that fit into 3 sentences. They routinely occur informally, most unassumingly in scientific literature. The reader doesn’t always need a science degree in order to detect them, because a fallacy, as a medium-specific narrative, can be expressed in the text itself, in a self-contained way.

Not all of science is equally vulnerable to fallacy. Compared to axiomatic science, empirical science as a collection of universal laws (e.g., “the action is always equal to the reaction”) is more “entertaining,” whether because of the leaps of faith that, as Hume pointed out, are required to elevate experimental observations to universal statements, or because of the wishful thinking underneath their justification, especially in the fields of applied science. For example, in The Logic of Scientific Discovery, Popper refutes the argument that his concept of “degree of corroboration of probability hypotheses” is reducible to traditional probability:

p(x) = 1/6; p(y) = 5/6; p(z) = 1/2.

Moreover, we have the following relative probabilities:

p(x, z) = 1/3; p(y, z) = 2/3.

We see that x is supported by the information z, for z raises the probability of x from 1/6 to 2/6 = 1/3. We also see that y is undermined by z, for z lowers the probability of y by the same amount from 5/6 to 4/6 = 2/3. Nevertheless, we have p(x, z) < p(y, z). This example proves the following theorem:

(5) There exist statements, x, y, and z, which satisfy the formula,

p(x, z) > p(x) & p(y, z) < p(y) & p(x, z) < p(y, z).

Obviously, we may replace here ‘p(y, z) < p(y)’ by the weaker ‘p(y, z) ≤ p(y)’.

This theorem is, of course, far from being paradoxical. And the same holds for its corollary (6) which we obtain by substituting for ‘p(x, z) > p(x)’ and ‘p(y, z) ≤ p(y)’ the expressions ‘Co(x, z)’ and ‘¬Co(y, z)’—that is to say ‘non-Co(y, z)’—respectively, in accordance with formula (1) above:

(6) There exist statements x, y and z which satisfy the formula

Co(x, z) & ¬Co(y, z) & p(x, z) < p(y, z).

Like (5), theorem (6) expresses a fact we have established by our example: that x may be supported by z, and y undermined by z, and that nevertheless x, given z, may be less probable than y, given z. There at once arises, however, a clear self-contradiction if we now identify in (6) degree of confirmation C(a, b) and probability p(a, b). In other words, the formula

(**) Co(x, z) & ¬Co(y, z) & C(x, z) < C(y, z)

(that is, ‘z confirms x but not y, yet z also confirms x to a lesser degree than y’) is clearly self-contradictory.

Thus we have proved that the identification of degree of corroboration or confirmation with probability (and even with likelihood) is absurd on both formal and intuitive grounds: it leads to self-contradiction. ❞However, formula (**) is not necessarily self-contradictory, both on intuitive and mathematical grounds. Let’s see why.

Popper provides a metaphor for formula (**): “x has the property P (for example, the property ‘warm’) and y has not the property P and y has the property P in a higher degree than x (for example, y is warmer than x).” Put like this, (**) certainly seems self-contradictory.

But Popper is misleading when he equates C(x, z) < C(y, z) to “y has the property P in a higher degree than x,” because by definition, this would mean we have “p(y, z) > p(y) to a higher degree than p(x, z) > p(x).” We are comparing 2 statements (“p(y, z) > p(y)” on one hand, and “p(x, z) > p(x)” on the other) each with a different right-hand side, namely p(x) and p(y). I can say that Alice is taller than Bob in a higher degree than Cedric is taller than David, but it’s not contradictory to say that Cedric is taller than Alice.

So a more accurate metaphor for P would be “warmer” rather than just “warm,” with an important emphasis on warmer than something. Obviously, if x gets warmer (Co(x, z)) and y cooler (¬Co(y, z)), y can still be warmer than x because it was very hot to start with, so having C(x, z) < C(y, z) (“y is warmer than something, to a higher degree than x is warmer than something”) doesn’t seem contradictory anymore.

Such losses in metaphor share with syllogisms the same propensity for erasing structural relationships through “honest mistakes” such as the shortcut from “warmer” to “warm.” They underly an infinite number of unique narratives that occur when translating back and forth between informal and formal language. Popper himself debunks Heisenberg’s use of informal language in what belongs to the long list of sensationalist interpretations of numbers and formulas that theoretical physics is especially fond of (e.g., the many-worlds interpretation, Schrödinger’s cat, time dilation):

Imagine a semi-translucent mirror, i.e. a mirror which reflects part of the light, and lets part of it through. The formally singular probability that one given photon (or light quantum) passes through the mirror, [math]\displaystyle{ (_αP_k(β)) }[/math], may be taken to be equal to the probability that it will be reflected; we therefore have

[math]\displaystyle{ (_αP_k(β) = _αP_k(\bar{β}) = {1 \over 2}) }[/math]

This probability estimate, as we know, is defined by objective statistical probabilities; that is to say, it is equivalent to the hypothesis that one half of a given class α of light quanta will pass through the mirror whilst the other half will be reflected. Now let a photon k fall upon the mirror; and let it next be experimentally ascertained that this photon has been reflected: then the probabilities seem to change suddenly, as it were, and discontinuously. It is as though before the experiment they had both been equal to [math]\displaystyle{ ({1 \over 2}) }[/math], while after the fact of the reflection became known, they had suddenly turned into 0 and to 1, respectively. It is plain that this example is really the same as that given in section 71. [That is to say, the probabilities ‘change’ only in so far as α is replaced by β. Thus [math]\displaystyle{ (_αP(β)) }[/math] remains unchanged [math]\displaystyle{ ({1 \over 2}) }[/math]; but [math]\displaystyle{ (_\bar{β}P(β)) }[/math], of course, equals 0, just as [math]\displaystyle{ (_βP(β)) }[/math] equals 1.] And it hardly helps to clarify the situation if this experiment is described, as by Heisenberg, in such terms as the following: ‘By the experiment [i.e. the measurement by which we find the reflected photon], a kind of physical action (a reduction of wave packets) is exerted from the place where the reflected half of the wave packet is found upon another place—as distant as we choose—where the other half of the packet just happens to be’; a description to which he adds: ‘this physical action is one which spreads with super-luminal velocity.’ This is unhelpful since our original probabilities, [math]\displaystyle{ (_αP_k(β)) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ (_αP_k(\bar{β})) }[/math], remain equal to [math]\displaystyle{ ({1 \over 2}) }[/math]. All that has happened is the choice of a new reference class—β or [math]\displaystyle{ (\bar{β}) }[/math], instead of α—a choice strongly suggested to us by the result of the experiment, i.e. by the information [math]\displaystyle{ (k \in β) }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ (k \in \bar{β}) }[/math], respectively. Saying of the logical consequences of this choice (or, perhaps, of the logical consequences of this information) that they ‘spread with super-luminal velocity’ is about as helpful as saying that twice two turns with super-luminal velocity into four. A further remark of Heisenberg’s, to the effect that this kind of propagation of a physical action cannot be used to transmit signals, though true, hardly improves matters. ❞Many fallacies share the liberal use of language, but their form and scale can vary from syllogisms to very elaborate theses.

Non-fiction literature

Prerequisite to rediscovery: stoicism in the face of contradictions, errors and dislikes. Being open-minded and not limited by taste.

One has absolute freedom to overlook the medium-specific narratives. So does the author of fallacies. They can freely overlook their “shortcomings”—I put that in quotes, because fallacies may be inconsequential, or even work out for the best. Most would agree that contradictions in a scientific theory should be cause enough to ditch it. Yet, a self-contradictory theory has no shame. It will outlive its intolerant readers. It weaves a tissue of contradictions, contradictions that break conventions, “don’t make sense,” or are so full of involuntary errors that even the author repudiated it. Just like science fiction, it doesn’t care.

When we ditch a logic system because it is self-contradictory, we do so for the same reason we ditch any other self-contradictory logic system: a single contradiction puts the whole system in jeopardy, since any proposition and its contrary can be logically derived from it. So, for example, if you prove 1 = 2, you can also prove 3 = 800. Yet the text that describes a self-contradictory logic system only mentions a very small subset of the infinite set of possible texts, and it does so in its own way. The confusion in Popper, as quoted in the previous section, is not only between the comparative and absolute forms, i.e., between “warm” and “warmer,” between “confirmed” and “confirmed to a higher degree.” There is a very medium-specific narrative that makes the confusion very peculiar. Popper makes the formula “Co(x, z) & ¬Co(y, z) & p(x, z) < p(y, z)” appear all the more self-contradictory because he first defined p(x, z) > p(x) as the absolute form Co(x, z) (“z confirms x”) which resembles C(x, z). This is a case where the fallacy highly depends on the presentation using a mix of formal and natural discourse: introduce an abbrevation Co(x, z) that makes it easy to define in an informal and amnesic way (“z confirms x” which forgets the precise form of the inequality p(x, z) > p(x)), then inject that informal definition in the formula C(x, z) < C(y, z) to obtain the contradictory-looking informal statement “z confirms x to a lesser degree than z confirms y”: there you have a medium-specific narrative.

The contradictions kind of “stop” the text. Not that one is forced to stop reading. The usual way people reconcile contradictions with the undisturbed flow of the text is by conceiving them as a mosaic of good and bad points. In other words, we fill the “holes” of the fallacies with the holes that make up the mosaic.

The stopping does not only apply to contradictions, but also to a whole repertoire of attention-grabbers: writing style, subject matter… anything, really, that can be valued. In music, we may stop listening to a death metal song after just a few notes just because the Cookie Monster vocals put us off. We may not finish a book because we disagree with its main points, or find it hard to care about the characters, or are just getting bored by the first pages. But even a boring start may lead to a rewarding overall experience. This applies to other media as well. In visual art, contradictions take the form of confusion, e.g., confusion between the mundane and the sublime, the lively and the still, the planar and the perspective, the colorful and the monochromatic, the imitative and the non-imitative, etc. In a movie, we may take issue with something bad, distasteful, repulsive. Yet the movie continues to live its life. We are the Jean-François Lyotard that Deleuze and Guattari criticized for “never ceasing to stop the process, to recall the schizes to the shores that he just left, coded or overcoded territories, spaces and structures, where they only bring ‘transgressions,’ disorders and distortions that remain secondary nonetheless.”

This discourse seems to echo the good old plea for open-mindedness. However, when people beg for open-mindedness, it is usually either in the hope of changing other people’s minds or with the mindset that others should have better tastes. In effect, the others are being criticized for their tastes, albeit in a politically correct way. “Be open-minded, what you don’t like is actually very good, you’ll see.” On the contrary, I absolutely don’t intend to change people’s minds about what they don’t like. What people didn’t like, they’ll still dislike, whatever it is they don’t like. I only speak from the perspective of the medium-specific narrative, which might very well be different from “what they don’t like,” although both are materially the same content. To use a metaphor: feces are distasteful and repulsive, a useless by-product (who would complain if we never had to defecate ever again?), yet this doesn’t take anything away from the elegance of a rural environment where one can defecate in the open and let Nature make it disappear in a matter of minutes, especially when compared to our artificial sewage systems.

Stoicism in the conventionalist interpretation of scientific literature.

The conventionalist interpretation of an axiomatic system consists in viewing the fundamental concepts as “implicit definitions:”

As Popper stresses, the conventionalist view, although unacceptable for some purposes, is unattackable: isn’t the conventionalist at liberty to consider a definition as he pleases? In fact, this view is unacceptable in Popper’s sense precisely because it makes any theoretical system unattackable. If a theory in geometry contains an axiom that states that a point has a surface, the conventionalist view does not claim that it is an actual observation or anything measurable. It is some definition of the point—or more accurately, the word “point.” Definition is only the arbitrary foundation to an arbitrary system. The focus is not the definition itself, but what one makes of it: something that can be aesthetical, witty, comical, or even useful. What if one invents a geometry where Euclid’s parallel postulate does not hold: “If a straight line falling on two straight lines make the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which are the angles less than the two right angles.” One could construe this as step toward elliptic/hyperbolic geometries and curved space, where basic theorems like the Pythagorean theorem or the triangle postulate—“The sum of the angles in every triangle is 180°”—do not hold anymore. This, in turn, helps to formulate the transition from special to general relativity in modern physics:

For some, this would be cause enough for ditching modern physics. Non-Euclidean geometry is neither intuitive, nor observable, nor simple—for what would be a space where “parallel” lines intersect? However, the non-intuitive theories may lead to the prediction of observable effects. And non-intuitive concepts can simplify theory:

But this implies that one first accepts the definitions as they are, rather than harping on them and potentially missing the point, such as the ability to make predictions or construct an elegant theory with practical applications.

Rediscovering philosophy

Even if it’s not considered art, a philosophical work (or any written work in general) has text-specific narratives. In a field where most problems originate from the definitions, the interpretation of a text-specific narrative has the tastefulness not to descend into the spiral of surmising with different definitions to prove one’s point. Instead, it reveals the uniqueness of a thought process.

A point can be made that without its false problems , philosophy would be boring. Its arguments would either be perfectly logical to the point of tautology, or verge on the mystic. For example, the talk about objectivity and reality would dumb down to the assertion that “objects” are external to me in the sense of their spatial relationship to my body. Granted, it wouldn’t be as interesting as speculating of an external reality “in-itself,” lying outside my perception. This is the classic case of a philosopher who creates “interesting” false problems that keep the next generations of philosophers busy for nothing. Ironically, these critics, being philosophers themselves, can’t help but make what is bred in the bone come out in the flesh. So there are some cases where the critic is spot-on, but in their own philosophy walks into pretty much the same traps as their peers—cf. Schopenhauer tackling Leibniz or Hegel.

Definition issues are often supported by selective amnesia. For example, the author presupposes A to prove some statement (in favor of the author’s thesis), then presupposes the antithesis of A (amnesia of the thesis of A) to prove another statement. Amnesia can happen at all scopes. At the phrase and paragraph level, amnesia can take the form of a traditional figure of speech. As the scope gets broader, amnesia takes more unique forms less acknowledged by academic literary analysis.

At the phrase level, take the infamous “DLC fiasco,” where a game editor, Capcom, delivers a game disc on the Playstation with locked content that can be unlocked for a fee. Then came the voices of protest:

But if “you just paid for a license,” then Capcom doesn’t revoke anything you paid for by locking away the content, since the lock is part of the license, which is where amnesia struck. Of course, this doesn’t mean people don’t have the right to be discontent, but they can’t expect to be any more legit than someone protesting that a car should come with all the accessories because the manufacturer has the keys to the warehouse.

At the paragraph level, in Anti-Œdipus Deleuze and Guattari take a bite at Freud’s Œdipus complex. In particular, they argue that incest is impossible in the system in which it exists:

In the quoted paragraph, “prohibited spouse” was replaced by “impossible spouse,” so that, indeed, it is now impossible to commit incest, since, by definition, incest now identifies mother and sister as impossible spouses—i.e., having sex with a woman makes her non-mother and non-sister, by definition.

In The Capital, Karl Marx demonstrates the laborer’s contribution to increased production:

Here the “advance of [more seed and manure] is made,” but in the concluding phrase of the paragraph, the increased production now occurs “without the intervention of any new capital.” This rhetorical trick allows Marx to make the labourers steal the show.

Gottlob Frege’s the Foundations of Arithmetic offers a good example of book-level amnesia. It enters a particular category, that of not keeping a promise made at the beginning of a book. The book starts with this:

Now, let’s teleport to the end of the book and examine Frege’s own definition of the “number”:

Therefore Frege’s Number relies on an “indefinite” (the “extension of concept”), and thus ends up doing what he warned not to do (not “stating which thing it is”).

Rediscovering repetition

Repetition is a significant tool of artistic expression. For example, the trope of the story loop, where the ending reflects the beginning, is quite common, from literature (e.g., Lewis Carrol’s Alice In Wonderland) to video games (e.g., The Last of Us, where the main protagonist carries to safety a girl the same way he carried his late daughter at the start of the game). In poetry, repetition of sound and structure has been thoroughly studied. Repetition is also a well-known comedic device—e.g., Monty Python’s Déjà Vu sketch.

A stone caught fire The castle caught fire The forest caught fire The men caught fire The women caught fire The birds caught fire The fish caught fire The water caught fire The sky caught fire The ashes caught fire The smoke caught fire The fire caught fire Everything caught fire Caught fire, caught fire.

❞As a result, the concept of repetition is commonly known as a trope. So although it is fundamentally a temporal concept, it seems to compress and abstract time. Same with the concept of tempo. In classical music, one is used to designate the sections of a concerto or symphony by a blanket tempo. A Vivaldi concerto, for example, is often divided into 3 movements identified by the tempo, usually: Allegro (fast), Largo (slow), then Allegro (fast). Each movement’s velocity is never as strictly uniform as the tempo would suggest. It’s as if velocity had been made into an atemporal category by abstracting away the velocity changes inside the movements.

Blanket concepts are a product of abstracting the medium-specific narratives into easily identifiable and well-known concepts. On the other hand, the more unique and granular the narrative, the less blanketable it becomes. For example, the aforementioned medium-specific narrative of Ode on a Grecian Urn doesn’t have (yet) a blanket term because it is fairly specific, although each step of the narrative is individually unremarkable. Some steps are a simple repetition, but are specific to the enclosing narrative. As a consequence of its specificity, the whole medium-specific narrative can only be communicated by going through all its steps in order, re-emphasizing the temporality of the structure.

Yet, blanket concepts sometimes pretend to capture uniqueness. For example, a music theory class may characterize Chopin’s music by its “question/answer structures.” The phrases played in succession on the piano almost sound like a dialogue between different instruments. But, come to think of it, one can actually say the same thing of any piece of music. It’s not only the phrases that engage into a dialogue. A phrase is divided into segments that compete to make their individual voices heard. Division is recursive and can reach down to the notes. The levels of division don’t have to be mutually exclusive; so smaller segments can enter into a dialogue with larger segments. The particular way in which a dialogue takes life is a medium-specific narrative, but the “question/answer structures” are such a broad description that they end up defeating the basic purpose of medium-specific narratives (which is to be specific).

Unique uses of repetition in medium-specific narratives cannot be described by blanket concepts. For example, William Faulkner’s A Light in August starts with a pregnant woman named Lena, on a quest to find her child’s father:

The first chapter ends with the following lines:

The last lines mirror the previous quotes:

The repetition highlights two changes in particular: her destination (Tennessee instead of Jefferson) and the transition from “I have come from Alabama […] I aint been on the road but four weeks” to “we aint been coming from Alabama but two months,” as she gave birth halfway through the book. The discovery of this indifference toward the destination since the beginning of the book (“I think she was just travelling. I dont think she had any idea of finding whoever it was she was following”) recontextualizes all that happens in-between the repeated bits (so the whole book, basically), as the reader realizes that the birth did wreak havoc in the lives of all the main characters, except “we”—Lena and the baby, who get the smoothest ride of all (“she had got along all right this far, with folks taking good care of her”).

The use of repetition to highlight a detail also underlies a medium-specific narrative of Yasmina Reza’s Dans la luge d’Arthur Schopenhauer. This time, the repetition is contained in a single sentence, the last one in the book.

The repetition in the last line makes the detail of the “ballooning dress” stand out. It is the finishing touch of a metaphor synthesizing themes developed in the previous chapters: the theme of turning around, the theme of coming back, as the old woman with the bags catches up to the relentless woman, and the “frivolity” of clothing details.

On both On Arthur Schopenhauer’s Sledge and A Light in August, repetition is used in a unique medium-specific way that eludes tropes and blanket concepts. The blatantness of repetition, especially in conjunction with the strategic placement (in the concluding lines of a chapter or the whole book), is able to attract attention to details of narratives which would easily get overlooked otherwise.

Rediscovering composite media

Intra-medium narrative versus composite media such as songs. “Medium pairing” as a value judgment versus the intra-heteromedium narrative.

The notions of medium specificity and of being intra-medium bring up the question “Which medium?” A composite medium is a combination of layers, e.g., a song can be seen as lyrics on top of an instrumental. I will use the term “heteromedium” when emphasizing this compositeness, and “intra-heteromedium” to qualify an interpretation limited to the content of a heteromedium.

To be perfectly accurate, what most would consider to be a monomedium is necessarily composite. Text has sound, syntax, semantics, structure, etc. Sound has tonality, rhythm, phrasing, texture, etc. Furthermore, not one such property can be made into a “truly” one-dimensional medium. Tonality cannot exist in a vacuum, just like color cannot exist without some sense of shape, or a line without some sense of thickness. Even so, we never pay attention to everything. It is not uncommon to ignore the lyrics in a song. Other parts of the medium may be deemed unessential depending on the listener. When listening to a heavy metal song, I will usually ignore the obligatory guitar solo every other chorus, the elaborate drum fills, redundant bass lines, etc.

Despite the fundamental heterogeneity of every medium, there has always been a sense of medium unity which has overpowered the other aspects of heteromedium interpretation. It is not uncommon to hear about how well lyrics match the music, the music the movie, the dancing the music, etc. The question as to how well the layers match is typically indicative of a value judgment. But as with all value judgments, even if there is objectivity in the match—e.g., rhythmic affinity between dance and music—the accompanying value judgment is fundamentally questionable. Nothing says that only positive affinity is necessary to make a “great” match. One could argue that happy lyrics go with dark music as a spooky combination—think porcelain doll in the dark—or as a spoof. On the other hand, dark lyrics over dark music can be of great comedic value if taken too seriously, for example satanic music in a world where Christianity has become irrelevant. What is taken seriously by some is easily derided by others. The song Black Sabbath may be taken seriously by “true heavy metal” fans and Satan-fearing parents, while others laugh off the cheesy horror lyrics. The fundamental separation between the evil theme and metal music is such that people could invent the genre of “white metal,” i.e., Christ-hailing metal. In any case, celebrating evil or god in songs is and has always been as deridable as the average self-proclaimed black metal misanthropes touring the world to party with their fans while promoting their latest album.

The act of viewing a medium as a composite medium for the purposes of value judgments, “medium pairing,” is not to be mistaken with the interpretation of a heteromedium-specific narrative. Narratives are about change, which statements on fitness for purpose (“the costumes fit the medieval fantasy theme so well!”) are not. So when one talks of “medium-specific narrative,” one considers changes across the medium pairing, not the pairing itself. Typically, the medium-specific narrative of a song (to mind: not album, not artist, but the individual song itself) focuses on melody, not style, genre, technique, or production (all invariants with respect to the narrative), and only deals with harmony insofar it partakes in producing melody. The purely musical narrative is usually tangent to the lyrics, although one can always try to look for narratives from the coupling of music with lyrics (rather than the meaning of music in lyrics, or the meaning of music in emotion), just like comics combine drawings and text into a particular type of narrative material, as was seen with Touti and his Exhaust Pipe.